The Bishkek Declaration of the recently concluded Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) declared the commitment of its member states to cooperate on one of the most significant non-traditional security issues- environment degradation and sustainable development. The inclusion of this sector is especially relevant for Central Asia as it grapples with acute water crisis, which has been further exacerbated by climate change. The availability of renewable water resources per capita has been declining across all Central Asian states, even as the threat of climate-change related hazards and desertification has become more imminent. The per capita renewable water resources have dwindled by approximately 14.4% in Kazakhstan, 22.1% in Kyrgyzstan, 33.4% in Tajikistan, 24.3% in Turkmenistan, and 25.7% in Uzbekistan over the past couple of decades.

As Central Asian republics pursue their national interests over cooperation, foregoing sustained intergovernmental political dialogue, water woes have persisted. In this situation, SCO offers hope of potentially facilitating cooperation and confidence building at the political level to help these nations overcome their trust deficit. India in its capacity as a full member of SCO also needs to examine its role in this area so as to further its aim of being an influential player in the region.

An overview of water problems in the Central Asia

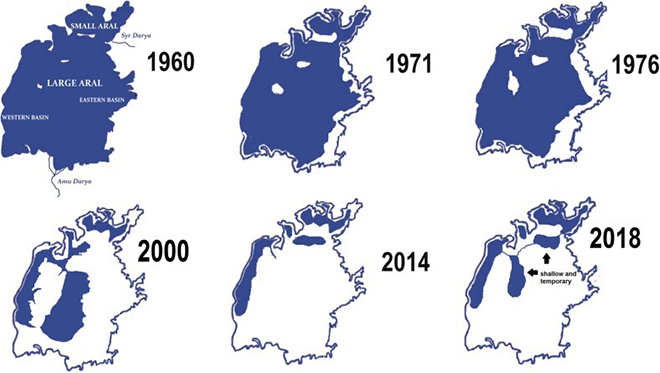

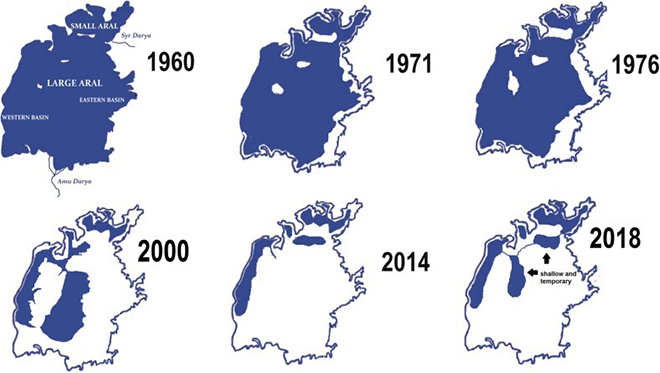

In recent years, a series of human errors has rendered Central Asia a hornet’s nest of ecological dangers. With desert covering over 60 per cent of its area, Central Asia is largely arid, which makes it even more susceptible to environmental disturbances. Due to over-irrigation, Central Asia is poised to have an inadequate supply of water. The desiccation of the Aral Sea, critical for agriculture and the sustenance of fishing communities, is the most conspicuous manifestation of the same.

Profile of Aral Sea over the last six decades.

Source: Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019; 26(3): 2228–2237.

Source: Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019; 26(3): 2228–2237.

For long, the region has relied on a

destructive cotton monoculture, requiring massive diversions from the two largest rivers that flow into the Aral Sea- Syr Darya and Amu Darya. Owing to reduced recharges, the Aral Sea split into two in 1990, and by 2003 the water level had fallen by 73 feet. As the Aral Sea has dried up, the communities inhabiting the shoreline and dependent upon fishing have seen their livelihoods disappear. The blowing dust from the exposed seabed has become a health hazard for communities residing near the basin. Further, owing to increased salinization and changes in water chemistry, there has been a serious deterioration in biodiversity and shifts in climate cycle.

Intensive irrigation and the consequent surface evaporation have ramped up soil erosion, causing deterioration in agricultural productivity. Due to global warming,

glaciers have receded by 30% since the 1960s, thereby jeopardizing a continuous supply of fresh water to lower riparian countries. Glacier losses have been the most pronounced in Tien Shan Mountains (located in the border region of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Xinjiang province of China) where 3000 km

2 of glacial area has been lost over this period. Over 50% of the current glacier mass in Central Asia is projected to be lost by the end of the century, and this would have further implications for precipitation patterns and river flow variability. Agriculture in Central Asia is largely irrigation dependent: 75 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s cultivated land is irrigated, 84 percent of Tajikistan’s, 89 percent of Uzbekistan’s and 100 percent of Turkmenistan’s. Restricted water supply would thus jeopardize food security in the region.

Water crisis- a historical legacy

Prior to 1991, the five Central Asian republics operated under a regional cooperative mechanism, operated and regulated by the Soviet Union. The two water-rich upstream countries, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, shared water with their three downstream counterparts (Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan) during summertime, in exchange of energy resources during the wintertime. However, this mechanism collapsed after the disintegration of USSR, and the situation that unfolded replicates the classic

Prisoner’s Dilemma (this refers to a situation where two/more states instead of cooperating to maximize payoffs choose not to do so, leading to mutual loss).

In 1992, the five republics signed the Almaty Agreement to maintain the status quo and continue with Soviet era water sharing arrangement. However, the upstream states believed that they were being denied their fair share of water, and began reducing the amount discharged to their downstream counterparts. The latter also found it more lucrative to export their energy resources to foreign countries, than to share them with their two upstream neighbors. In response, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan began producing hydropower to meet their energy requirements, which created further water shortages for the downstream countries. Thus, due to grave mistrust and lack of political will to cooperate, the countries went on to pursue their own national economic priorities, and ended up with an outcome worse than the cooperative equilibrium.

Effective cooperation has remained elusive not only because of divergent national interest, but also due to differing approaches to regional water management. The downstream countries favor maintaining old Soviet Union quotas, whereas the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan are in favor of receiving payment for water supplied to the downstream states. There’s a discord over whether water should be treated as a commodity or a public good, and also over whether domestic or international water law should be applied for the resolution of the disputes.

Can SCO be a potential platform for cooperation?

Central Asia’s woes are as political in nature, as they are economic. The trust deficit at the government level inhibits the sharing of key resources between surplus and deficit states. Central Asia’s water woes will require a uniquely political solution, for which multilateral cooperation might be a precondition.

The SCO Charter regards as one of the main areas of cooperation the provision of ‘sound environmental management, including water resources management in the region, and implementation of specific joint environmental programs and projects.’ This will has since been reiterated by the member states in several declarations.

The members have agreed to fight climate change through coordinated action and welcomed the signing of the ‘Action Plan on Implementing the Concept of Cooperation in Environmental Protection”, as well as the agreements reached at the 24th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in Katowice on the guiding principles for the practical realization of the Paris Agreement. A commitment to the consistent implementation of Sustainable Development Goals 2030 remains a recurring theme. Additionally, over the years, they have acknowledged the importance of promoting renewable sources of energy and minimizing carbon footprint.

SCO has therefore emerged as a prospective platform that could potentially facilitate cooperation over Central Asia’s water woes. It now needs to take concrete actions to make good on its commitments. Russia, China and India are regional giants and can provide Central Asia with technical expertise to help diversify its agriculture away from water-intensive crops, enhance and maintain its water distribution infrastructure, and adopt modern irrigation practices as well as environmentally sound technologies. In fact, China has already launched an

online platform where the member countries, dialogue partners and observers of SCO can share information to improve regional environments and realize sustainable development. China’s presence also becomes crucial given that most of the Central Asian rivers originate therein. With the help of increased scientific engagement, Central Asian states would hopefully be able to come up with economically viable management practices and adaption strategies to cope up with their water problems.

Conclusion

PM Narendra Modi has expressed India's commitment towards an active engagement with SCO and noted environmental protection as one of the goals the multilateral organization should aspire for in 2018. Towards this goal, India can use the multilateral organization to establish a working group to deal with climate change, share knowledge on environmental protection and find solutions for efficient water management. India can also collaborate with SCO member states in the areas of R&D and agritech to work out solutions to common problems. Inclusion of private sector can also be explored in the area to use innovative technologies to aid water preservation and bolster sustainable development.

Anubhav Agarwal, is a Research Intern at ORF, New Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Bishkek Declaration of the recently concluded Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) declared the commitment of its member states to cooperate on one of the most significant non-traditional security issues- environment degradation and sustainable development. The inclusion of this sector is especially relevant for Central Asia as it grapples with acute water crisis, which has been further exacerbated by climate change. The availability of renewable water resources per capita has been declining across all Central Asian states, even as the threat of climate-change related hazards and desertification has become more imminent. The per capita renewable water resources have dwindled by approximately 14.4% in Kazakhstan, 22.1% in Kyrgyzstan, 33.4% in Tajikistan, 24.3% in Turkmenistan, and 25.7% in Uzbekistan over the past couple of decades.

As Central Asian republics pursue their national interests over cooperation, foregoing sustained intergovernmental political dialogue, water woes have persisted. In this situation, SCO offers hope of potentially facilitating cooperation and confidence building at the political level to help these nations overcome their trust deficit. India in its capacity as a full member of SCO also needs to examine its role in this area so as to further its aim of being an influential player in the region.

The Bishkek Declaration of the recently concluded Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) declared the commitment of its member states to cooperate on one of the most significant non-traditional security issues- environment degradation and sustainable development. The inclusion of this sector is especially relevant for Central Asia as it grapples with acute water crisis, which has been further exacerbated by climate change. The availability of renewable water resources per capita has been declining across all Central Asian states, even as the threat of climate-change related hazards and desertification has become more imminent. The per capita renewable water resources have dwindled by approximately 14.4% in Kazakhstan, 22.1% in Kyrgyzstan, 33.4% in Tajikistan, 24.3% in Turkmenistan, and 25.7% in Uzbekistan over the past couple of decades.

As Central Asian republics pursue their national interests over cooperation, foregoing sustained intergovernmental political dialogue, water woes have persisted. In this situation, SCO offers hope of potentially facilitating cooperation and confidence building at the political level to help these nations overcome their trust deficit. India in its capacity as a full member of SCO also needs to examine its role in this area so as to further its aim of being an influential player in the region.

Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV