-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Poor governance and flawed policies marred Nepal’s economic performance.

This piece is part of the essay series, Instability in India’s neighbourhood: A multi-perspective analysis

The current economic situation of Nepal does not look promising for a nation looking for foreign investments. Increasing trade deficit, rapidly declining foreign exchange reserve, and skyrocketing inflation have hit the life of ordinary people and crippled Nepal’s economy. The Russian–Ukraine conflict and the COVID-19 pandemic are the prime causes of the dismal economic situation. However, in the true sense, a lack of good governance and apathy on the part of the state can be held responsible for the present economic downturn of the country.

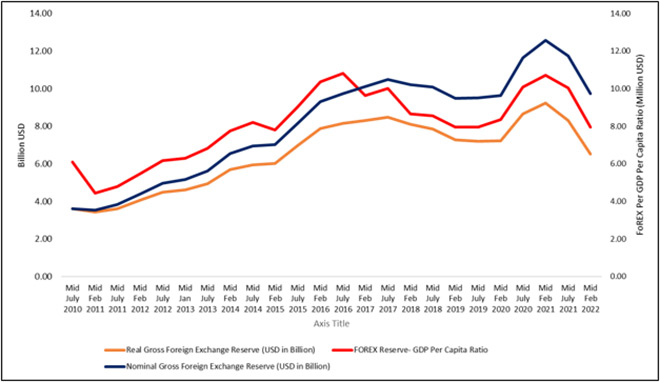

The foreign exchange reserves (forex) of the country are depleting. The Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) noted forex reserves to be around US $ as of mid-April this year. This amount was less than US $2 billion compared to mid-April last year. As a result, analysts suggest that the country can hold imports only for another six and a half months. A detailed review of Nepal’s foreign exchange reserves trends, reveals interesting trends since 2010 (Figure 1).

Nominal forex i.e. forex in current price has increased significantly from mid-February 2020 to mid-February 2021 but started declining from mid-February 2021 onwards. Remittances, the main source of forex in Nepal contributes around 50 percent to the total reserve pool, while import cost is the main cause of the decline in forex. Interestingly, remittances in Nepal increased despite the pandemic, while imports in the period between mid-February 2020 and mid-February 2021 significantly reduced, which led to the unusual growth in the foreign reserves. The World Bank attributes the rise in remittances to six main reasons that could have played out during the COVID-19 outbreak. Primarily, two reasons could be at work in Nepal out of the six. First, people abroad remitted money through formal channels such as banks and other financial services companies during the pandemic. The informal channel (Hundi), a system of transferring money through the network of people instead of formal channels, is one of the most popular channels in the country, and may not have worked during that period.

Another possible reason for the rise in forex could be the high volume of remittances sent by Nepalese abroad for the security of their family back home. They either sent their savings or took loans to send money to their families in Nepal. However, a reduction in remittances is observed post relaxations in COVID-19-related restrictions. This trend is evident from the reduction in the volume of foreign reserves in the stated period until mid-Feb 2022. Another reason for the decrease in forex reserve post-February 2021 could be the resumption of imports that was put on hold during the pandemic.

Figure 1: Nepal's foreign currency reserve over time

Data Source: FOREX Reserve (Nepal Rastra Bank), GDP per capita (The World Bank ), Inflation of USA (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis)

Data Source: FOREX Reserve (Nepal Rastra Bank), GDP per capita (The World Bank ), Inflation of USA (Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis)

The inflation-adjusted forex and the forex reserve to GDP per capita ratio have also declined after mid-February 2021, indicating a declining purchasing power of the country in the foreign market. However, they are not at the historically lowest level. All these values are almost equal to the values in mid-February 2015. Before mid-February 2015, the values of all three indicators were lower than the current level.

What do we conclude from these trends? Although the foreign reserves are declining, they are still not at the level to cause a serious threat to the Nepali economy. However, the trends do require policy attention since the country is experiencing a trade deficit.

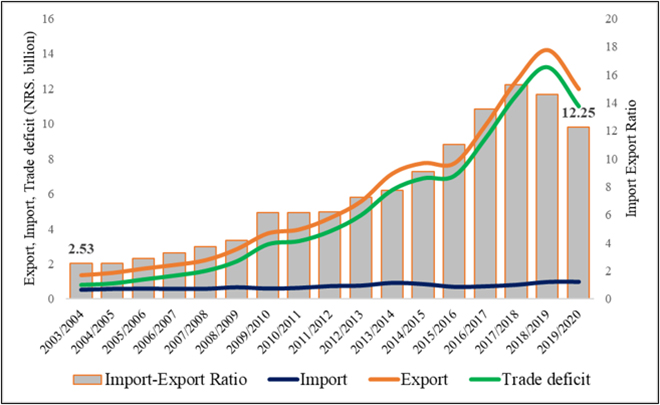

Imports are on the rise, while exports are relatively low. Nepal’s high trade deficit is not a new phenomenon. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Direction of foreign trade in Nepal

Data Source: Nepal Rastra Bank (Current macro-economic and financial situation)

Data Source: Nepal Rastra Bank (Current macro-economic and financial situation)

As depicted, the trade deficit of Nepal is on the rise every year. Nepal’s trade deficit between 2003–04 and 2019–20 increased by around 13-fold. Most worrisome is the fact that the import-export ratio of the country has skyrocketed. That is to say, in 2003–04, for exports worth NPR. 1, the country imported NPR. 2.5 worth of goods. It is alarming to observe that in 2019–20 for the same level of exports, the country imported goods worth NPR. 12. This trend indicates structural issues facing the economy. Production, which is limited by insufficient private and public investment, must increase to increase export. The prevailing tax policy, market size, availability of raw materials for manufacturing, wage rate, quality of technology, cost of transportation, and labour productivity are not conducive for investments in Nepal. Poor performance on these indicators has discouraged investments, resulting in lower levels of production and productivity. To elaborate, the market size defined in terms of the population of Nepal is small and the GDP per capita of the people (US $1,155) is also the lowest in South Asia after Afghanistan. In an estimate by the Asian Productivity Organisation, the productivity of the Nepalese workforce is the lowest in South Asia. Similarly, as per the World Development Indicator, the value-added per worker in Nepal is lower than that of Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, and China by 2.3, 3.3, 6.2, and 15.7 times, respectively. Nepal's value-added per worker in 2019 was US $1,749 while US $ 27,436 for China. On the other hand, data from various sources reveal that the minimum wage of a worker in Nepal is the highest in South Asia. Another important factor that impacts production and export is the quality of infrastructure. As per the data from the World Bank, the quality of infrastructure is based on the opinion of respondents on a one to seven-point Likert scale, with one being extremely underdeveloped and seven being amongst the best in the world. The above data establish that Nepal is in the weakest position in terms of investment climate, production, and productivity. All these lead to poor export performance. Nepal exports lose out on global competitiveness due to the high cost of production and low productivity.

Low productivity and high production cost have also left Nepal with a low product base. Nepal does not have its original product exported in a large quantity. Most high-volume export products are imported from other countries and exported to India with small value addition. For example, while in 2019, Nepal's major export item was palm oil, in 2020, it was soybean oil. Both of these products are not Nepal's original products. Carpet, jute, tea, coffee, and cardamom are major products that Nepal produces and exports.

As per the latest Nepal Rastra Bank data, the inflation rate of Nepal is 7.28 percent. The rate is likely to increase in the days ahead. Policymakers believe that an inflation rate around 2 percent or below is acceptable. In the recent past, after the devastating earthquake in 2015, Nepal's inflation rate hovered around 4.25 percent (an average for 2017–2021). The current higher inflation is due to the disturbance in the supply chain brought about by the Russia–Ukraine war, price hikes in petroleum products, the rising value of US dollar, massive expenditure (about NPR 100 billion, almost 2.5 percent of GDP) during the latest local level elections in the country as well as the ban imposed on the imports of luxury goods.

The current economic situation, i.e., increasing prices and depleting forex, may deteriorate food security. It is estimated that about 4.6 million people in Nepal are food-insecure. Rising food prices may put more people out of access to food. In the meantime, at least fourteen countries, including India, have banned food export. Since Nepal is a net importer of food grain, restrictions on food export by these countries may further worsen the situation.

There is a growing fear amongst the general public whether Nepal will face a fate similar to that of Sri Lanka, given the escalating rate of inflation and high trade deficit. However, as the economic structure of Sri Lanka and that of Nepal are different, Nepal may escape the same fate. For example, Nepal has far less external debt compared to Sri Lanka. Besides, the contribution of tourism to the Nepalese economy is comparatively low. To be precise, Sri Lanka needs to repay the foreign debt worth US $4 billion this year whereas the debt service of Nepal for this year stands at only US $400 million only. Likewise, while the contribution of tourism to the GDP of Nepal is around 3 percent, its contribution to the GDP of Sri Lanka is around 12 percent. As such, because of these two reasons, Nepal is less likely to be like that of Sri Lanka given the situation. Besides, the structure of loans Nepal has to service are different from that of Sri Lanka. In the case of Nepal, its debt comprises mainly the soft loan with lower interest rates whereas the foreign debt of Sri Lanka mostly comprises commercial loans.

Nepal’s current economic situation does ring alarm bells that it is time the country initiates appropriate steps towards increasing production and productivity. Poor governance, especially lack of transparency, accountability, effectiveness, and efficiency is of prime concern. Formulating evidence-based economic policies that encourage transparency and accountability can save Nepal from an economic crisis similar to that of Sri Lanka with the help of highly skilled human resources and by implementing them effectively.

Unfortunately, the prevailing political mechanism and bureaucracy appear reluctant to take such initiative. Nepal’s governance is characterised by corruption and nepotism.

The country’s economy still hinges on remittance and traditional farming. Thus, Nepal’s economy may suffer a major setback if these issues are not resolved. It is pertinent to conclude this work with the remark of former Vice-Chairman of the Nepal Planning Commission and Chief Economic Advisor at the UNDP Regional Bureau for Asia and the Pacific (RBAP) in New York, Dr Swarnim Wagle, who says, “We are like Sri Lanka not in terms of economic indicator and structure but in terms of bad governance and flawed policy.”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dadhi Adhikari is an Economist with more than fifteen years of experience working in the field of development economics and teaching graduate students in Nepal. ...

Read More +