Pakistan is currently facing a standstill due to a backlog of imports and reduced export volumes, which is gradually depleting its fragile foreign exchange reserves. Intensive discussions have been ongoing between the Pakistani authorities and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to address the economic crisis in Pakistan through a new financing arrangement. Eventually, on 29 June 2023, the IMF team announced a staff-level agreement with the Pakistani authorities for a nine-month Stand-by Arrangement (SBA) valued at

SDR 2,250 million (equivalent to around US$ 3 billion or 111 percent of Pakistan's IMF quota). However, the approval of this agreement is still pending and is expected to be reviewed by the IMF's Executive Board in mid-July.

The government promptly implemented austerity measures to avert a probable default on foreign debt as well as import bans on all goods except food and medical items.

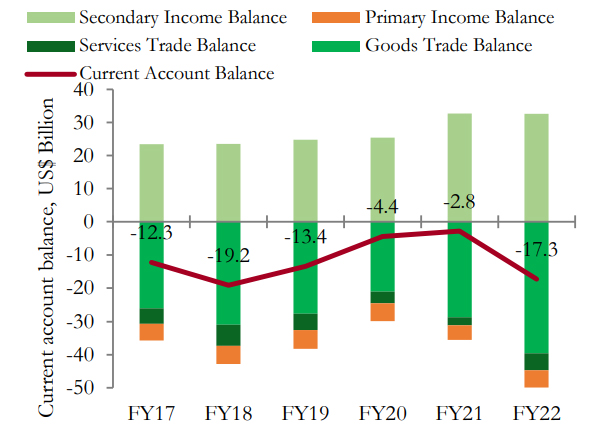

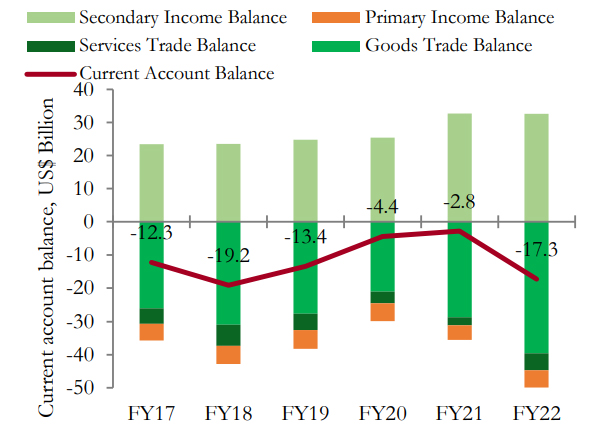

For Pakistan, the inflated Current Account Deficit (CAD) stood at

US$ 17.4 billion in FY22, a significant increase compared to the US$ 2.82 billion gap in FY21. The government encountered challenges following severe floods in 2022, leading to a loss of confidence among creditors and a decline in foreign exchange reserves. In response, the government promptly implemented austerity measures to avert a probable default on foreign debt as well as import bans on all goods except food and medical items. Following these efforts, the country's CAD experienced a significant decline earlier this year, reaching

US$ 242 million in January 2023 (a 21-month low). However, Pakistan's foreign exchange reserves plummeted to US$ 3 billion, rendering the economy susceptible to external macroeconomic shocks. In January 2023, compared to the same month the previous year, export revenues and worker remittances both fell noticeably in the country by 7 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

Figure 1: Pakistan's Current Account Balance (in US$ billion)

Source: The World Bank

Source: The World Bank

Unfortunately, the government's protectionist measures and import restrictions had unintended consequences for many domestic industries in Pakistan. These industries heavily rely on imported inputs to sustain their production, with intermediate goods accounting for

53 percent of total imports. Consequently, widespread disruptions occurred throughout the economy, leading to high attrition rates, reduced export productivity, and significant commodity chain disruptions.

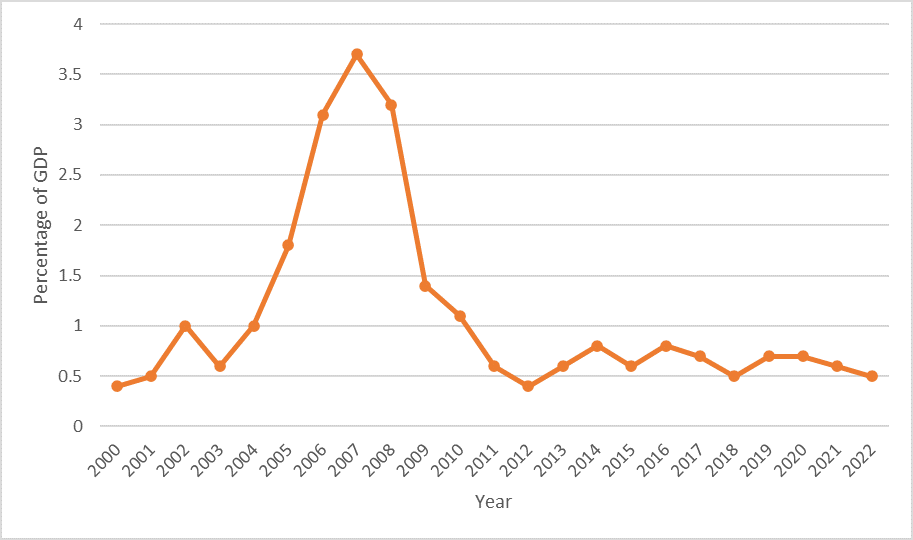

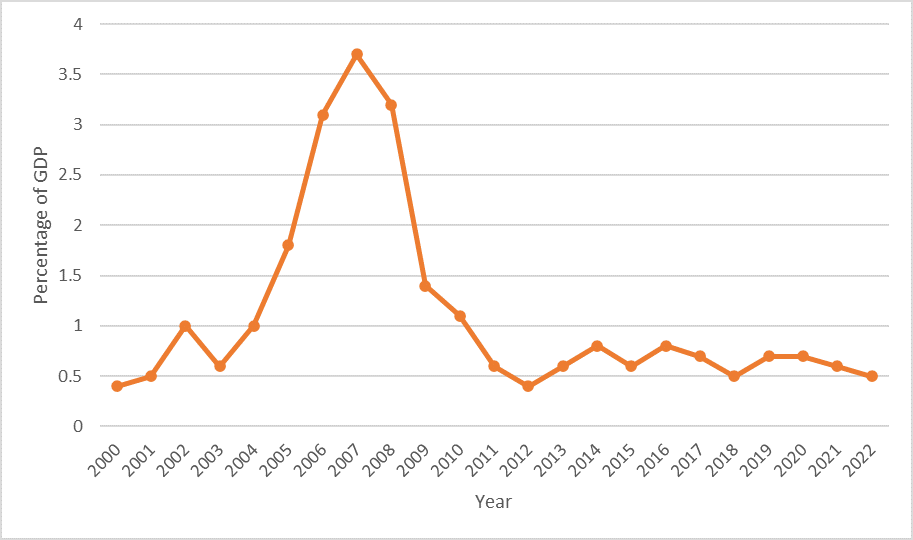

FDI movements

Economic progress is severely hampered as the country faces a worsening situation of the Balance of Payments (BoP), with deepening deficits in both the current and capital accounts. In terms of the capital account, Pakistan is experiencing a

decline in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows, largely due to the unstable and hostile business environment in the country. Pakistan's investment environment has invariably been marked by high tariff rates, political unpredictability, terrorist concerns, strict tax and interest rate laws, and demanding security clearance requirements. These elements have discouraged foreign investment and made it difficult for international investors to fund domestic enterprises.

As a result, private investment in Pakistan has stagnated at around

10 percent of GDP, which is significantly lower than its South Asian counterparts and only about a third of more dynamic emerging Asian economies. Such low levels of private investment have contributed to dull productivity with low efficiency across various sectors. The decline in FDI and inadequate technology transfer have had a detrimental impact on labour productivity growth, leading to diminished gains from production and inaccessible scale economies in the country for the past two decades.

Pakistan's investment environment has invariably been marked by high tariff rates, political unpredictability, terrorist concerns, strict tax and interest rate laws, and demanding security clearance requirements.

In fact, between 2003 and 2007, Pakistan experienced a notable

increase in FDI inflows, driven by a combination of favourable factors—domestic as well as external. The Pakistani government implemented various measures to enhance security and boost investor confidence during this period. Economic reforms were introduced to liberalise and deregulate the economy, streamline bureaucratic processes, and stimulate private sector growth. These changes increased the avenues for FDI inflow and enhanced the business climate. Additionally, the government started privatisation initiatives, offering both domestic and foreign investors appealing investment opportunities.

Furthermore, the groundwork for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) was laid during this time, which was complemented by increased investments from China and other regional countries. However, Pakistan's energy crises, political unrest, shoddy infrastructure, and the 2007-08 financial crisis continued to hamper foreign investment and the nation's economic advancement.

Figure 2: Pakistan's Foreign Direct Investment (percentage of GDP)

Source: Author's own, data from the World Bank

Source: Author's own, data from the World Bank

BoP-constrained growth model

The decline in Pakistan's exports can be attributed to the low investment and savings cycle, which leads to the drainage of foreign currency from the country's reserves. In addition to these factors, another significant deterrent for foreign investors is Pakistan's limited integration with the global and, especially, regional economy.

The lack of industrialisation in the country impedes the productivity and competitiveness of producers, shifting the domestic consumption preference towards imported goods and widening the trade deficit. The inability to grow exports in the face of a constantly depreciating currency is indicative of the prevalent inefficiency across sectors. The

capacity to generate exports is at a standstill in Pakistan, compared to other emerging economies. This does not bode well for the recovery of Pakistan’s BoP, which will require prolonged amendments to be brought down to sustainable levels.

The inability to grow exports in the face of a constantly depreciating currency is indicative of the prevalent inefficiency across sectors.

Pakistan seems to fit in a BoP-constrained growth model where a simultaneous worsening of the external balance accompanies any development in the growth rate. The country is expected to grow at

3.8 percent, when adjusted for its BoP and structural parameters. Hence, to break out of this cycle, the nation must undertake several trade and diplomatic measures. Revitalising its lax export capacity, diversification, and broadening the trade base is necessary, and, instead of subsidising profits, greater emphasis must be laid on increasing productivity.

Expanding the range of exported goods beyond textiles and rice and improving

trade openness can contribute to the growth of Pakistan's economy and increase its foreign exchange reserves. To achieve this, Pakistan should learn from countries like the Philippines and Vietnam, which have outperformed Pakistan in terms of trade openness. It is crucial for Pakistan to diversify its foreign investment partnerships beyond its current allies of China, Saudi Arabia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates. By forging new diplomatic relationships and establishing effective ties, Pakistan can attract more capital inflows and further enhance its economic prospects.

Note – For a more detailed analysis, please see ORF Occasional Paper No. 403 “Debt ad Infinitum: Pakistan’s Macroeconomic Catastrophe”

Soumya Bhowmick is an Associate Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy, at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Pakistan is currently facing a standstill due to a backlog of imports and reduced export volumes, which is gradually depleting its fragile foreign exchange reserves. Intensive discussions have been ongoing between the Pakistani authorities and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to address the economic crisis in Pakistan through a new financing arrangement. Eventually, on 29 June 2023, the IMF team announced a staff-level agreement with the Pakistani authorities for a nine-month Stand-by Arrangement (SBA) valued at

Pakistan is currently facing a standstill due to a backlog of imports and reduced export volumes, which is gradually depleting its fragile foreign exchange reserves. Intensive discussions have been ongoing between the Pakistani authorities and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to address the economic crisis in Pakistan through a new financing arrangement. Eventually, on 29 June 2023, the IMF team announced a staff-level agreement with the Pakistani authorities for a nine-month Stand-by Arrangement (SBA) valued at

PREV

PREV