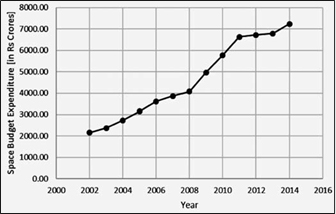

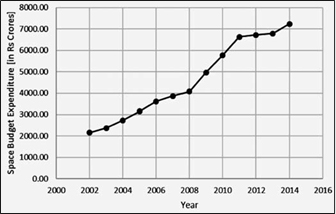

The Indian space programme is one of the world’s fastest growing (Figure 1). Backed by investments for over five decades now, India is moving towards increasing its capacity and capabilities of using space technology products and services not only for societal applications but also to support commercial space activities and pursue diplomatic and security objectives. Thus there is an inherent potential to exploit the technological prowess developed in the country for homegrown enterprises to expand products and services for the domestic market as well as participate in the $300-billion global space industry.

Figure 1 - Evolution of India’s Space Budget1

- Traditional Space in India

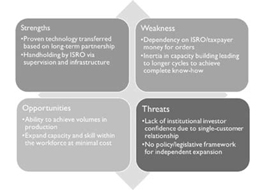

In order to understand the business ecosystem and the aspirations of Indian space industry for expansion, it is important to acknowledge the strengths and weaknesses of traditional business models in the space sector. Today, India has a large Small-Medium-Enterprises (SMEs) base that caters within the traditional space agency-driven model. The phenomenon of encouraging the development of India’s private sector in the space domain began in the 1970s when the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) started handholding entrepreneurs in technology transfer initiatives with the safety net of buybacks to ensure business survivability.2 Fast forward four decades, today there are new initiatives being taken to encourage the complete development of end-to-end systems in both launch vehicles3 and satellites4 by the private industry.

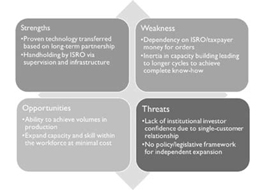

Figure 2 provides an overview of a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) for the traditional space approach. What traditional space approach tries to do is to increasingly offload work that is considered to be routine to the industry as an initiative in capacity building to achieve volumes that might not be possible without a significant increase in the infrastructure and manpower within a space agency. This is no doubt a significant step in helping the Indian industry to further mature and be able to perform Assembly, Integration and Testing (AIT) of both rockets and satellites. However, the current measures are more top-down in nature, and mostly based on capacity building via development of industry in upstream.

Figure 2 - SWOT Analysis of Traditional Space in India

This step will elevate vendors in the space programme to the next level, working alongside the space agency to be able to deliver back complete end-to-end systems. However, this current form of capacity building where a partnership is envisioned to perform AIT-related aspects (in both launch vehicles and satellites) is an extremely elementary one since the know-how transferred in this process is mostly at the system level of integration and does not entail capacity building to design, develop and complete end-to-end systems independently.

Although this is definitely a jump up for the industry in acquiring the know-how on AIT aspects, the roadmap for the traditional vendors to get to a level of being able to design, develop and manufacture end-to- end launch vehicles or satellites is not on the horizon until the current initiatives attain fruition and begin to show signs of sustainability. Therefore, this track is more a top-down model that enables the industry over long gestation periods to systematically develop capacity and primarily feeds on taxpayer funding to execute projects.

This model of industry engagement is not exclusive to India. Most traditional space business models work on this framework where the industry is funded largely by the government to deliver end-to-end systems. However, what is different between advanced spacefaring nations and India in terms of current models is the level of capacity builtup in the private industry. As a country, India is one of the most successful nations to have developed the capacity to deliver payloads to space or to develop satellites for services or to interplanetary missions. However, there is a stark gap in the capacity builtup in the private industry where the industry is mostly involved as tier-based vendors and presently there is no single industry vendor who has the capacity to deliver end-to-end systems. This creates bottleneck effects in the possible expansion of industry to the global supply chain, especially from an export perspective.

However, traditional space approach has a strong edge of having room for building upon proven and reliable technology and handholding from the space agency. Policymakers should look to draw a long-term roadmap in creating an environment of multiple industry players or industry consortiums having the ability to deliver end-to-end systems so that there is room for competition in the national ecosystem.

The current outlook for traditional space approach in India is positive with the initiatives of stepping of industry participation in launch vehicles and satellites. From a market perspective, the present outlook makes it certain that traditional space suppliers will be limited to upstream capacity building and will not be able to participate in completely commercial frameworks in the downstream.

The traditional space industry ecosystem will definitely benefit from long-term perspective planning by policymakers. Building a long-term perspective plan where the industry is enabled to participate in a complete commercial model where end-to-end systems shall be delivered can help in not only meeting the growing requirements in volumes nationally but also in integrating the Indian industry base globally.

- NewSpace in India

NewSpace is a worldwide phenomenon of entrepreneurs developing products, and service enterprises focusing on space and are using private funding in their initial developments. While there is no internationally accepted technical definition of ‘NewSpace’, principally, the ethos of the movement has been to challenge the traditional ways of space exploration that are widely considered as too expensive, time-consuming, and lacking in room for inventive risk-taking. Companies that fit in the bracket of NewSpace include the likes of SpaceX, OneWeb, and Planet Labs, which are primarily funded by private capital to build products and services that challenge the cost to either access to space itself or access to services based out of assets in space.

NewSpace has gone on to attract successful global entrepreneurs to either kick-off ventures of their own or to support start-ups. Examples of such global entrepreneurs include the likes of Richard Branson kicking off Virgin Galactic, Jeff Bezos starting up Blue Origin, and Larry Page backing Planetary Resources.5 One can argue that NewSpace kicked off where traditional space enterprises were stifling with the cost for creating more assets in space in areas such as developing cheaper rockets with greater launch cadence and developing satellite constellations that can enable greater and faster coverage to now many of them diversifying into space tourism and mining of space resources.

While this phenomenon has largely been orchestrated for the past decade and a half with leadership from the US, with the revolution in small satellites and the cost to access to space being reduced substantially, there are 10,000 NewSpace enterprises expected to kick-off around the world in the next 10 years.6 Even if this may be an estimate that is ten times over what is realisable, having some 1,000 NewSpace companies in the next 10 years can well change the very nature of space exploration and exploitation. The key question here from a NewSpace perspective that needs to be asked is this: Will India have, if not a dominant, at least a relevant global NewSpace footprint or will it be a closed self-serving ecosystem?

NewSpace has inspired several Indian entrepreneurs to form companies that can inspire a whole new generation of fellow Indians to dream of businesses based on space products and services. The ecosystem is very recent with start-ups in a mix of both upstream and downstream offerings such as Team Indus, Earth2Orbit, Astrome Technologies, Bellatrix Aerospace, and SatSure. The spread of these companies include dreams of landing a rover on the Moon,7 developing space-based internet service,8 developing a private launch vehicle,9 and using space data to change the face of how space-based technology can be used to provide forecast and insights to important basic sectors such as agriculture.10

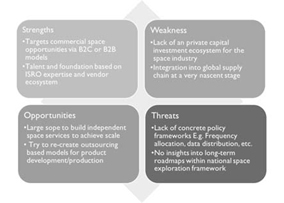

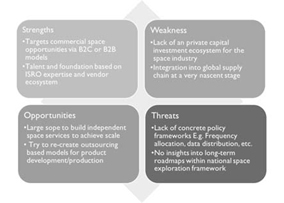

Figure 3 provides an overview of a SWOT analysis for NewSpace in

India. The key question is how different these start-ups are from those 500-odd small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) that serve ISRO. The answer lies in the rather simple fact that these companies are the ones that plan to build either end-to-end systems or services for the first time in the country. Their business model is more diversified, with the possibility of either serving (private businesses or consumers themselves) customers themselves directly. Another strong distinction from the traditional business models that exist so far in the country is their vision to focus on the possibility of exporting their offerings.

It is important to understand that enabling NewSpace in India will have an effect not only on young start-ups with but it also gives an opportunity for the already built-up SMEs to expand their business. NewSpace in this sense is not a phenomenon but more of a framework that can act as an enabler to expand capacity and capability for the industry to offer end-to-end products and services.

Figure 3 - SWOT Analysis of NewSpace in India

NewSpace India will look to feed on successes such as the most cost- effective and the only first-time success mission to Mars as a brand-building exercise and shall try to translate it into international business for homegrown industries as a recognition of producing world-class products and services. Therefore, NewSpace offers the potential for diversification of customer base for Indian industry in the space sector at the global level.

The government of India has actively floated several key initiatives such as ‘Make in India’ and ‘Digital India’, in which the space industry has a key role to play in achieving the goals. With the backbone technology know-how foundation in place, mainly by the efforts of ISRO and its vendor base, there is immense scope for NewSpace enterprises to leverage these cluster-based externalities such as technologies, infrastructure and manpower to build space-based services.

The investments needed for NewSpace commercial enterprises are extremely large since the target is to build end-to-end products and services models. Therefore, one of the major challenges will remain to convince private capital investors to buy into the business models. This exercise is also challenging due to the fact that there is no long-term framework within the national goals for NewSpace in India alongside concrete policy frameworks.

However, there is immense scope for effecting change in the commercial space landscape and achieving economies of scale in space- based services if NewSpace is enabled. Parallels can be drawn to the rise of the IT industry which enabled the creation of an environment that today is one of the pillars of export activity in the country.

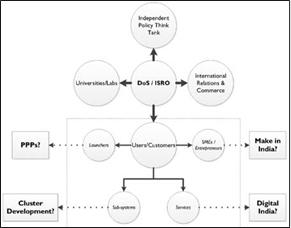

- Need for a Cluster Mapping & Competitiveness Study

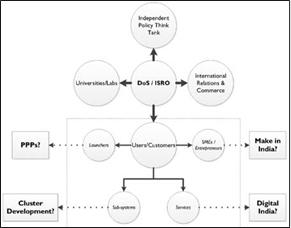

A comprehensive mapping of the Indian space industry ecosystem (Figure 4) will help managers, policymakers from both India and abroad, to take advantage of the opportunities available in the country including the talent pool, inherent growing market requirements within, and the already established capacity to deliver highly reliable technology products and services.

3.1. Benefits for Indian Industry

- Successes such as the most cost-effective and the only first-time success mission to Mars must act as a brand-building exercise and should translate to international business for homegrown industries as a recognition of producing world-class products and services. Therefore, cluster development is an important exercise in the diversification of customer base for Indian SMEs and greater integration of Indian vendors into the global supply chain.

- With the backbone technology know-how foundation in place, mainly by the efforts of the ISRO, there is immense scope for these technologies to trickle down to domestic industry via focused initiatives to encourage cluster externalities. These can be in the form of spin- ins or spinoffs, which can emerge as innovative business models for products and services for these new offerings for both India’s market and allied ones.

- Effective cluster mapping and positioning to achieve collaborative partnerships between Indian and international firms can lead to SMEs in the country to learn from international partners to work with new standards (e.g., European Cooperation for Space Standardization). Such an exercise can spread the capacity within the industry to replicate

the success achieved in the auto-industry within the country.

- One of the critical needs in the current landscape for the SMEs in the country is the need to access capital to achieve a larger scale in capabilities and capacity.11 Provided that India has a very niche and nascent investment ecosystem for a sector such as space, the clustering exercise can help Indian SMEs to attract attention for possible FDI, Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A) or Joint Ventures (JV) with international partners that will bring mutual benefit.

Figure 4–Need for Cluster Mapping & Competitiveness Study

- The government of India has actively floated several key initiatives such as ‘Make in India’ and ‘Digital India’, in which the space industry has a key role to play in achieving the goals set out under these missions. Therefore, a cluster-based network study can help policymakers to gain key insights to actively align policy decisions to further encourage the inclusive growth of the Indian industry and academia.

3.2. Perspectives for Global Players to Invest in Indian

Space Industry

- With India recently permitting 100-percent FDI in the space sector,12 there is an opportunity for international firms to gain a market entry into India by positioning their offerings independently or by integrating their marker strategies via partnerships (via JVs, M&As or SPVs) with Indian SMEs to realise end-to-end upstream and downstream systems offerings.

- Take advantage of the local market conditions (e.g.,talent pool, low labour costs, engineering services backbone, and others) to replicate the cost-competitive IP creation and co-creation in the country that has been a construct that global firms have already used successfully in technology sectors such as aerospace and IT.

- The space industry is a niche sector with several global pockets for vendors for specialised products and services. Knowledge of the local industry cluster of a market such as India can potentially help consolidate their supply chain and mitigate some of the inherent supplier risks and well as solve single-vendor problems for global firms.

- There is a difference in the route to innovation pursued by firms in developed countries and emerging economies. Innovations in emerging economies tend to not involve major technological breakthroughs but take a more novel and innovative combination of existing knowledge and technologies to solve pressing local problems by using new processes and business models. This makes a case for international firms to utilise India as a hub for ‘reverse innovation’ before ‘trickling up’ to either allied markets in emerging economies or developed countries themselves.

- For example, General Electric’s ultra low-cost ultrasound and ECG machines, were led by development teams in India, initially for use in these countries, but with inputs from local and foreign subsidiaries.13

- Based on the long-term strategy, global firms can typically benefit by exploiting India as a foundation for improvising growth strategy under competitive pressures by developing expansion plans as a part of larger global strategy, increasing speed to market, improving service levels, business process redesign, adopting an industry practice, testing differentiation strategy, access to new markets, enhancing system redundancy.

- Conclusion and Recommendations

The current outlook for traditional space approach in India is positive with the initiatives of stepping of industry participation in launch vehicles and satellites. NewSpace start-ups in India plan to either build end-to-end systems or services for the first time in the country with diversified business models bringing the possibility of either serving (private businesses or consumers themselves) customers themselves directly including possible export-oriented models.

The current ecosystem can be further fostered by developing mechanisms of continuous tracking and monitoring to provide a strong foundation in enabling business from a policy framework perspective. To this end, there is scope for initiating the ‘State of the Space Industry’, which can draw a lot of inspiration from similar practices in the international space industry to provide the outside world an overview of the current Indian capabilities in ISRO and in the industry. This can help showcase to foreign companies the relevance of working with their Indian counterparts.

There are several other broad ways of promoting growth that need to be considered with measures to promote Indian space industry. These include the following:

- Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) awards for Indian companies to be given at the Bangalore Space Expo in different categories such as ‘Best SME’, ‘Best space spin-off ’, ‘Best space start-up’, among others.

- Starting a space directory of companies, capabilities, and others, which is easily accessible to anyone in the international markets so that it can promote ease of doing business by increasing networks.

- Promoting Indian industry to participate with ISRO in the largest space conference in the world – the International Astronautical Congress (IAC).

Finally, it is important to understand that traditional space and NewSpace may be different approaches but they both aim to expand the country’s space economy.

This article originally appeared in Space India 2.0

REFERENCES

1. Narayan Prasad Nagendra and Prateep Basu, “Space 0: Shaping India’s Leap into the Final Frontier,” Occasional Paper #68, Observer Research Foundation, August 2015,

http://dhqxnzzajv69c.cloudfront.net/wp- content/uploads/2000/10/OccasionalPaper_68.pdf.

2. R. Sridhara Murthi and Mukund Kadursrinivas Rao, “India’s Space Industry Ecosystem: Challenges of Innovations and Incentives,” New Space 3, (2015): 165–71, doi:10.1089/space.2015.0013.

3. Srinivas Laxman, “Plan to Largely Privatize PSLV Operations by 2020: Isr o Chief,” T he Times of India, Fe br uar y 15, 2016,

http:// timesofindiatimes.com/india/Plan-to-largely-privatize-PSLV- operations-by-2020-Isro-chief/articleshow/50990145.cms.

4. Alnoor Peermohamed, “Isro Plans to Launch First Privately Built Satellite by March,” Business Standard India, September 3, 2016,

http:// www.business-standarcom/article/current-affairs/isro-plans-to-launch- first-privately-built-satellite-by-march-116090300204_1.html.

5. Jesse Riseborough and Thomas Biesheuvel, “Google-Backed Asteroid Mining Venture Attracts Billionaires,” Bloomberg.com, August 7, 2012, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-08-06/google-backed- asteroid-mining-venture-adds-billionaire-investors.

6. Caleb Henry, “NextSpace Edition 2016 - Six Investor Expectations for the NewSpace Sector,” Via Satellite, accessed September 17, 2016,

http://interactive.satellitetoday.com/via/nextspace-edition-2016/six-investor- expectations-for-the-newspace-sector/.

7. Hari Pulakkat et al., “Here’s How Bengaluru-Based Startup Team Indus Is Reaching for the Moon,” The Economic Times, accessed September 17, 2016,

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/small-biz/startups/heres- how-bengaluru-based-startup-team-indus-is-reaching-for-the-moon/ articleshow/53089062.cms.

8. Madhumathi D. S, “A Dream to Beam Internet from Space,” The Hindu, Se ptember 4, 2016,

http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/ karnataka/a-dream-to-beam-internet-from-space/article9070456.ece.

9.

Bellatrix Aerospace, “Garuda,”

http://www.bellatrixaerospace.com/ garuda.html.

10.

SatSure, “About Us,”

http://www.satsure.in/#aboutUs.

11. V. P. Kharbanda, “Facilitating Innovation in Indian Small and Medium Enterprises – The Role of Clusters,” Current Science 80(3) (2001): 343–48.

12.

Make In India, Government of India, “Make in India - SPACE,” http://

www.makeinindia.com/sector/space.

13. Vijay Govindarajan and Ravi Ramamurti, “ Reverse Innovation, Emerging Markets, and Global Strategy,” Global Strategy Journal 1, (2011): 191–205, doi:10.1002/gsj.23.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Indian space programme is one of the world’s fastest growing (Figure 1). Backed by investments for over five decades now, India is moving towards increasing its capacity and capabilities of using space technology products and services not only for societal applications but also to support commercial space activities and pursue diplomatic and security objectives. Thus there is an inherent potential to exploit the technological prowess developed in the country for homegrown enterprises to expand products and services for the domestic market as well as participate in the $300-billion global space industry.

The Indian space programme is one of the world’s fastest growing (Figure 1). Backed by investments for over five decades now, India is moving towards increasing its capacity and capabilities of using space technology products and services not only for societal applications but also to support commercial space activities and pursue diplomatic and security objectives. Thus there is an inherent potential to exploit the technological prowess developed in the country for homegrown enterprises to expand products and services for the domestic market as well as participate in the $300-billion global space industry.

Figure 1 - Evolution of India’s Space Budget1

Figure 1 - Evolution of India’s Space Budget1

Figure 2 - SWOT Analysis of Traditional Space in India

This step will elevate vendors in the space programme to the next level, working alongside the space agency to be able to deliver back complete end-to-end systems. However, this current form of capacity building where a partnership is envisioned to perform AIT-related aspects (in both launch vehicles and satellites) is an extremely elementary one since the know-how transferred in this process is mostly at the system level of integration and does not entail capacity building to design, develop and complete end-to-end systems independently.

Although this is definitely a jump up for the industry in acquiring the know-how on AIT aspects, the roadmap for the traditional vendors to get to a level of being able to design, develop and manufacture end-to- end launch vehicles or satellites is not on the horizon until the current initiatives attain fruition and begin to show signs of sustainability. Therefore, this track is more a top-down model that enables the industry over long gestation periods to systematically develop capacity and primarily feeds on taxpayer funding to execute projects.

This model of industry engagement is not exclusive to India. Most traditional space business models work on this framework where the industry is funded largely by the government to deliver end-to-end systems. However, what is different between advanced spacefaring nations and India in terms of current models is the level of capacity builtup in the private industry. As a country, India is one of the most successful nations to have developed the capacity to deliver payloads to space or to develop satellites for services or to interplanetary missions. However, there is a stark gap in the capacity builtup in the private industry where the industry is mostly involved as tier-based vendors and presently there is no single industry vendor who has the capacity to deliver end-to-end systems. This creates bottleneck effects in the possible expansion of industry to the global supply chain, especially from an export perspective.

However, traditional space approach has a strong edge of having room for building upon proven and reliable technology and handholding from the space agency. Policymakers should look to draw a long-term roadmap in creating an environment of multiple industry players or industry consortiums having the ability to deliver end-to-end systems so that there is room for competition in the national ecosystem.

The current outlook for traditional space approach in India is positive with the initiatives of stepping of industry participation in launch vehicles and satellites. From a market perspective, the present outlook makes it certain that traditional space suppliers will be limited to upstream capacity building and will not be able to participate in completely commercial frameworks in the downstream.

The traditional space industry ecosystem will definitely benefit from long-term perspective planning by policymakers. Building a long-term perspective plan where the industry is enabled to participate in a complete commercial model where end-to-end systems shall be delivered can help in not only meeting the growing requirements in volumes nationally but also in integrating the Indian industry base globally.

Figure 2 - SWOT Analysis of Traditional Space in India

This step will elevate vendors in the space programme to the next level, working alongside the space agency to be able to deliver back complete end-to-end systems. However, this current form of capacity building where a partnership is envisioned to perform AIT-related aspects (in both launch vehicles and satellites) is an extremely elementary one since the know-how transferred in this process is mostly at the system level of integration and does not entail capacity building to design, develop and complete end-to-end systems independently.

Although this is definitely a jump up for the industry in acquiring the know-how on AIT aspects, the roadmap for the traditional vendors to get to a level of being able to design, develop and manufacture end-to- end launch vehicles or satellites is not on the horizon until the current initiatives attain fruition and begin to show signs of sustainability. Therefore, this track is more a top-down model that enables the industry over long gestation periods to systematically develop capacity and primarily feeds on taxpayer funding to execute projects.

This model of industry engagement is not exclusive to India. Most traditional space business models work on this framework where the industry is funded largely by the government to deliver end-to-end systems. However, what is different between advanced spacefaring nations and India in terms of current models is the level of capacity builtup in the private industry. As a country, India is one of the most successful nations to have developed the capacity to deliver payloads to space or to develop satellites for services or to interplanetary missions. However, there is a stark gap in the capacity builtup in the private industry where the industry is mostly involved as tier-based vendors and presently there is no single industry vendor who has the capacity to deliver end-to-end systems. This creates bottleneck effects in the possible expansion of industry to the global supply chain, especially from an export perspective.

However, traditional space approach has a strong edge of having room for building upon proven and reliable technology and handholding from the space agency. Policymakers should look to draw a long-term roadmap in creating an environment of multiple industry players or industry consortiums having the ability to deliver end-to-end systems so that there is room for competition in the national ecosystem.

The current outlook for traditional space approach in India is positive with the initiatives of stepping of industry participation in launch vehicles and satellites. From a market perspective, the present outlook makes it certain that traditional space suppliers will be limited to upstream capacity building and will not be able to participate in completely commercial frameworks in the downstream.

The traditional space industry ecosystem will definitely benefit from long-term perspective planning by policymakers. Building a long-term perspective plan where the industry is enabled to participate in a complete commercial model where end-to-end systems shall be delivered can help in not only meeting the growing requirements in volumes nationally but also in integrating the Indian industry base globally.

Figure 3 - SWOT Analysis of NewSpace in India

NewSpace India will look to feed on successes such as the most cost- effective and the only first-time success mission to Mars as a brand-building exercise and shall try to translate it into international business for homegrown industries as a recognition of producing world-class products and services. Therefore, NewSpace offers the potential for diversification of customer base for Indian industry in the space sector at the global level.

The government of India has actively floated several key initiatives such as ‘Make in India’ and ‘Digital India’, in which the space industry has a key role to play in achieving the goals. With the backbone technology know-how foundation in place, mainly by the efforts of ISRO and its vendor base, there is immense scope for NewSpace enterprises to leverage these cluster-based externalities such as technologies, infrastructure and manpower to build space-based services.

The investments needed for NewSpace commercial enterprises are extremely large since the target is to build end-to-end products and services models. Therefore, one of the major challenges will remain to convince private capital investors to buy into the business models. This exercise is also challenging due to the fact that there is no long-term framework within the national goals for NewSpace in India alongside concrete policy frameworks.

However, there is immense scope for effecting change in the commercial space landscape and achieving economies of scale in space- based services if NewSpace is enabled. Parallels can be drawn to the rise of the IT industry which enabled the creation of an environment that today is one of the pillars of export activity in the country.

Figure 3 - SWOT Analysis of NewSpace in India

NewSpace India will look to feed on successes such as the most cost- effective and the only first-time success mission to Mars as a brand-building exercise and shall try to translate it into international business for homegrown industries as a recognition of producing world-class products and services. Therefore, NewSpace offers the potential for diversification of customer base for Indian industry in the space sector at the global level.

The government of India has actively floated several key initiatives such as ‘Make in India’ and ‘Digital India’, in which the space industry has a key role to play in achieving the goals. With the backbone technology know-how foundation in place, mainly by the efforts of ISRO and its vendor base, there is immense scope for NewSpace enterprises to leverage these cluster-based externalities such as technologies, infrastructure and manpower to build space-based services.

The investments needed for NewSpace commercial enterprises are extremely large since the target is to build end-to-end products and services models. Therefore, one of the major challenges will remain to convince private capital investors to buy into the business models. This exercise is also challenging due to the fact that there is no long-term framework within the national goals for NewSpace in India alongside concrete policy frameworks.

However, there is immense scope for effecting change in the commercial space landscape and achieving economies of scale in space- based services if NewSpace is enabled. Parallels can be drawn to the rise of the IT industry which enabled the creation of an environment that today is one of the pillars of export activity in the country.

Figure 4–Need for Cluster Mapping & Competitiveness Study

Figure 4–Need for Cluster Mapping & Competitiveness Study