-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Recent focus on convergence-based institutionalisation of bilateral ties has consolidated India-US defence ties, without the overbearing pressures of a formalised alliance

Speaking in New Delhi early this month, US Deputy Secretary of State Stephen Biegun underscored a different approach for partnerships. In context of the Indo-Pacific region, while Biegun acknowledged the criticality of the United States’ post-World War II treaty alliances in underwriting peace and prosperity for about seven decades, the US diplomat expressed the need for recalibrating partnerships to better “reflect the geopolitical realities of today and tomorrow.” Although Biegun noted some alliances (as with Japan and Australia) to have already evolved to a degree, he noted the redundancy of following “the model of the last century of mutual defence treaties with a heavy in-country US troop presence.”

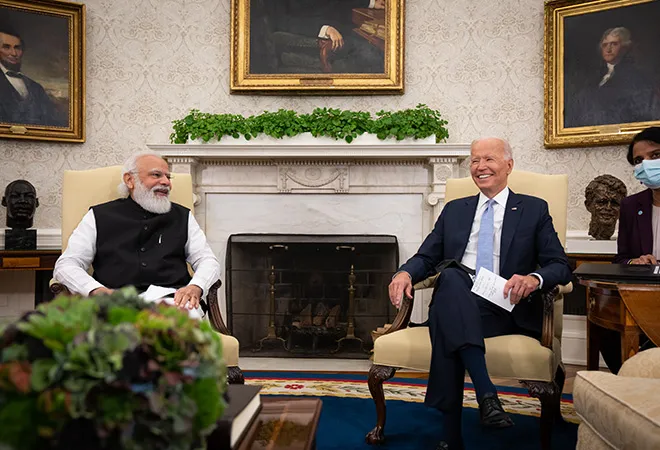

Biegun noted India to be one such partner with which the US has an emerging “organic and deeper partnership — not an alliance on the postwar model, but a fundamental alignment along shared security and geopolitical goals, shared interests, and shared values.” Given recent developments under the US-India bilateral dynamic, there is much credence to that assessment as a renewed model for management of bilateral ties has been apparent in recent years. To which, the upcoming the India-US 2+2 ministerial dialogue bears testament.

Slated for October 27 in New Delhi, India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar and Defence Minister Rajnath Singh will host their American counterparts, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Secretary of Defence Mark Esper. This will be the third iteration of the India-US 2+2 consultative dialogue between the two sides, since it was initiated after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s first meeting with US President Donald Trump in 2017.

The same was indicative of the Trump administration’s intent to continue its predecessor Barack Obama administration’s push for instituting definite frameworks and standardised communication channels between India and the US. Furthermore, the India-US 2+2 ministerial dialogue replaced the India-US Strategic and Commercial dialogue between the two sides’ foreign and commerce ministers, which was initiated under Obama in 2015.

The value of which, was apparent when trade frictions emerged under the Trump administration’s effort to exact renewed “fair and reciprocal” trading arrangements with America’s partners.

Subsequently, this indicated a sense of greater nuance to the need for institutionalisation of bilateral ties — towards not only graduating the bilateral dynamic away from over-dependence on chemistry between the top political leadership, but also design frameworks in a manner that maximise convergences between the two countries. The value of which, was apparent when trade frictions emerged under the Trump administration’s effort to exact renewed “fair and reciprocal” trading arrangements with America’s partners. As a result, over the last three years, as trade negotiations continually stalled over either long-standing market-access issues or nascent divergences like that over digital trade, US-India strategic ties progressed nearly unhindered.

The inaugural India-US 2+2 dialogue for instance, witnessed the two sides committing to “start exchanges between the US Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) and the Indian Navy.” Whereby, the Indian Navy even announced that the defence attaché at the Indian embassy in Bahrain would subsequently “double up” as India’s representative at NAVCENT. This was crucial with regards to India and the US aligning their conceptions over the relevance of the north-west Indian Ocean region under the Indo-Pacific construct.

Similarly, the second iteration of the 2+2 dialogue oversaw the finalisation of the Industrial Security Annex (ISA) to “facilitate the exchange of classified military information between Indian and the US defence industries.” The same is an important step towards the long-belated actualisation of the Obama-era Defence Technology and Trade Initiative’s (DTTI) goal of graduating India-US defence ties away from a traditional “buyer-seller” dynamic and towards one based on co-production and co-development.

Since its establishment in 2018, the US-India Strategic Energy Partnership ministerial dialogue between India’s Minister of Petroleum and Natural Gas and the US Energy Secretary has overseen bilateral hydrocarbon trade to increase to US$ 9.2 billion in 2019-20.

The focus on maximising convergences through specific consultative platforms has also been apparent with other strategic avenues. For instance, India and the US have identified complementarities between the Modi government’s aim to “diversify its

This focus on convergences and its institutionalisation through dedicated frameworks alleviates the pressures on the two sides to urgently contemplate formalisation of ties.

This emergent model of managing bilateral ties has also permitted greater military preparedness – on both sides – without the pressures of entering a formal arrangement like the one Biegun described. As a case in point, building on the Obama administration’s work on the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA), the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement (COMCASA) was signed at the inaugural India-US 2+2 dialogue. LEMOA, COMCASA and last year's ISA cemented India’s buy-in to the described model of convergence-based institutionalisation with the US, and is set to go further this year with the signing of the final 'Foundational Agreement' – the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) for Geo-Spatial Cooperation at this week's 2+2 dialogue.

LEMOA was signed in 2016, allowing both parties to benefit from each other's logistics infrastructure, resources and consumables, while 2018's COMCASA enables secure communications between the forces and governs access to sensitive US communications equipment and encryption.

The four Foundational Agreements serve as a framework for cooperation and interoperability between the US military and international partners such as India, with the first of these, the General Security Of Military Information Agreements (GSOMIA) signed in 2002 to enable the sharing of classified data between Government entities (but crucially, not private companies, which the ISA resolved last year). After protracted negotiations, LEMOA was signed in 2016, allowing both parties to benefit from each other's logistics infrastructure, resources and consumables, while 2018's COMCASA enables secure communications between the forces and governs access to sensitive US communications equipment and encryption. Whereas, BECA will allow the US to share satellite and other surveillance data to improve Indian navigation and targeting capabilities.

While LEMOA has already seen Indian warships refuel using US Navy tankers at sea and US patrol aircraft transit Port Blair, COMCASA and BECA will facilitate closer non-kinetic cooperation during crises such as the 2017 Doklam incident and the ongoing LAC stand-off. It is worth noting that while the USA was reported to have shared intelligence with India during the Doklam issue, that cooperation was inherently limited by the lack of formal structures to enable rapid, secure dissemination of information.

Despite a raft of defence agreements in recent years, increasingly complex joint exercises such as the tri-service Tiger Triumph series that began last November, and even strong US messaging on the recent India-China stand-off at the LAC, it is worth reiterating Biegun's point that India-US military cooperation is not an alliance and is not leading to one. The US will not fight India's wars, nor will the reverse be expected, but the burgeoning ties do reinforce a message – that of the US as a useful partner.

Just as India benefited from US inputs during Doklam and may well be doing so again at the LAC in 2020, the US has benefited from Indian defence spending, including LAC-related emergency buys this year.

Wherein, India stands to gain significantly from the United States' global footprint in terms of logistics and intelligence, and will benefit from American situational awareness, especially in the region, thanks to COMCASA and BECA. Nor is the relationship one-sided – just as India benefited from US inputs during Doklam and may well be doing so again at the LAC in 2020, the US has benefited from Indian defence spending, including LAC-related emergency buys this year. As Indian forces increasingly value US military hardware as being transparently priced and predictable to operate and maintain, the US will continue to benefit from being part of India's military ecosystem going forward.

Absent true interoperability, these limited – but significant – convergences are worth keeping in mind in both capitals as the two countries explore the limits of what strategic cooperation can enable.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Angad Singh was a Project Coordinator with ORFs Strategic Studies Programme. ...

Read More +

Kashish Parpiani is Senior Manager (Chairman’s Office), Reliance Industries Limited (RIL). He is a former Fellow, ORF, Mumbai. ...

Read More +