-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The sanctions imposed on Russia is weighing down the global economy as supply chains are affected.

The Ukraine crisis brings home the fragility of the passive equilibrium, based on the absence of war rather than the absence of a need for war. Equitable and empowered global rule-making, which inspires trust and respect amongst all nations is still some way-off. Till it becomes a reality, there will always be the temptation to arbitrage security gaps through quick territorial gains.

Pretended peace is seductive. It became convenient to ignore the fulminations of a missile-happy North Korea as mere domestic posturing, by an inward-looking and economically islanded regime, intent on survival. Magnify the same intent to a military superpower like Russia, China, or the United States (US), and the world looks decidedly unsafe sans a global intermediation mechanism deriving its ability to act decisively from explicit institutional recognition of changing geoeconomic and, therefore, geopolitical fundamentals.

In the absence of an effective mediating institution, it has suited the western alliance, led by the US, to ignore Russian security concerns and expand NATO coverage eastwards. It has incentivised Russia to play spoiler and acquire disputed assets militarily. It enables China to sit on the fence, emboldening Russia by not condemning its military action because it simultaneously highlights the waning ability of the western alliance to enforce an equitable, global peace. It similarly provides India an opportunity to further its near-term national interest by abstaining from condemning Russia, a long-term military hardware supplier and a strategic partner.

Practical, cost-conscious Europe is a free-rider on US defence expenditure, in exchange for tipping its top-hat from time to time, acknowledging US’ global technological and military reach.

Even Europe is complicit in turning a Nelson’s eye to Russia’s intransigence in using military force to annex Crimea (2014). Russia was reprimanded mildly, because access to cheap natural gas and Europe’s carbon emission objectives are tied at the hip. Practical, cost-conscious Europe is a free-rider on US defence expenditure, in exchange for tipping its top-hat from time to time, acknowledging US’ global technological and military reach. The US, in turn, finds it convenient to offshore management of distant geopolitical hotspots—across the Atlantic or the Pacific oceans—thereby allowing the American economic juggernaut to continue creating wealth.

India is no stranger to the kind of brinkmanship which Ukraine faces. India, too big to swallow and also too large to leave undisciplined, has been at the receiving end of Chinese unilateral aggression. Like Ukraine, India has been resolute in standing up to a forced redrawing of the disputed border with China, despite a resort to armed conflict.

But as the relative strengths of the two Asian neighbours has diverged over the last three decades, India has become much more respectful of Chinese sensibilities on the issue. Diplomacy, negotiation, and accommodation has successfully contained the dispute from blowing out into a serious military engagement of the kind that India has been willing to undertake against Pakistan—a more vulnerable opponent.

A similarly guarded response to China’s brinkmanship is seen from ASEAN, Japan, and South Korea against China’s claims in the South and East China Sea. Despite considerable aggravation, the “absence of war” doctrine has been maintained.

Diplomacy, negotiation, and accommodation has successfully contained the dispute from blowing out into a serious military engagement of the kind that India has been willing to undertake against Pakistan—a more vulnerable opponent.

It suits the US to continue the “make-believe” narrative that a growing China is no threat to it or the world. A prosperous and resilient China, hungry for commodities and adept at low-cost manufacturing to suit all pockets, has surely been the global economic kicker which enabled high consumption levels, shored up global growth rates, and reduced global poverty over the past three decades. But as its economy has prospered, so have its global ambitions.

Institutional limitations in constraining aggressors have created a piquant situation where economic sanctions seek to bleed the aggressor country economically—a hands-off option in comparison to the messier one of confronting the aggressor militarily. But sanctions on an economy like Russia that is linked to global wheat, crude and gas, and metals trade and the consequential uncertainty in the Black Sea region—a hub for regional shipping—has immediate negative global impacts.

Coming as it does, on the back of the pandemic, it extends the global supply disruptions for an indeterminate period. Should the conflict extend into an impasse, alternative supply routes and sources can develop over time—the existing Iranian sanctions could be diluted, production can be stepped up in existing oil wells and payment sanctions’ workarounds can emerge, as in the case of Iran—although Russian production of oil at over 10 million barrels per day is more than three times of Iran’s and consequently less easy to camouflage.

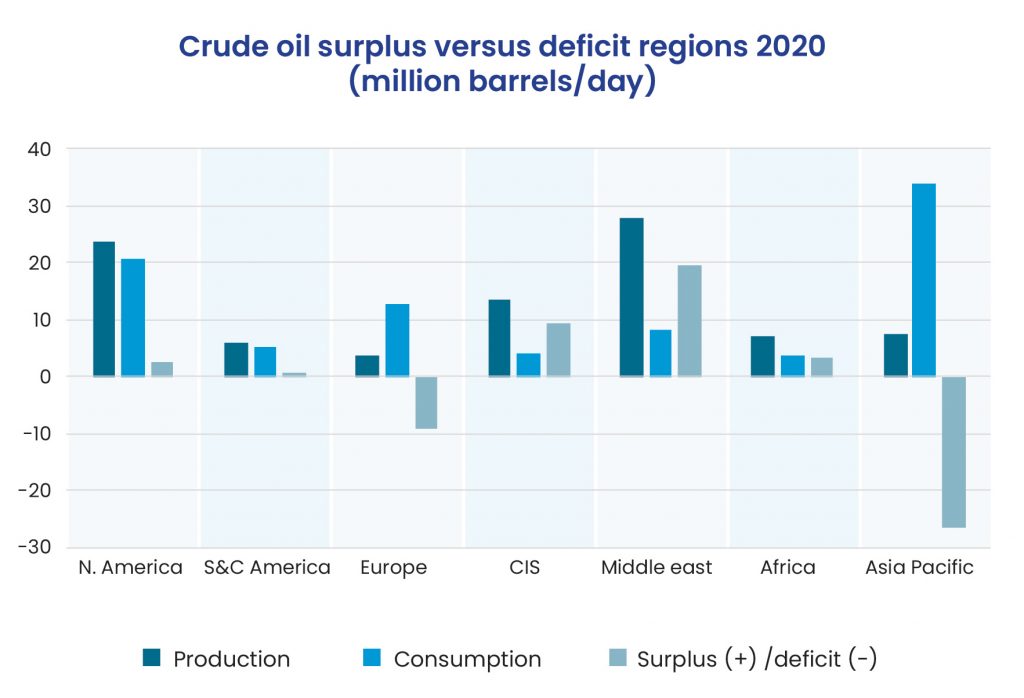

The table below illustrates the asymmetric effect that sanctions on the sale of Russian oil could have on regions. Asia Pacific is the region hungriest for oil. The table makes a simplistic assumption that regionally produced oil can be consumed internally. This is untrue beyond North America because the alignment of oil transportation pipes might not be helpful, even in Europe. More importantly, refineries are configured for a target crude oil variety (ranging across four types from light and volatile to heavy, non-fluid oil). The problem is larger than depicted here.

Source: BP Statistical review 2020

Source: BP Statistical review 2020

On a per capita income basis, the 25 low-income economies (other than Sudan and South Sudan) and more than two-thirds of the 55 lower middle-income economies (according to World Bank data 2020), including India, are net importers of oil.Around 60 economies across regions, but concentrated in North America, South, and Latin America, Central Asia and Russia, and the Middle East are net oil exporters whilst most other economies, predominantly in Europe, Asia Pacific (other than Australia and Malaysia) and in Africa (barring North and parts of West Africa), are net importers.

A fuel price increase will hit these vulnerable economies the hardest. In the poorest economies, sans the fiscal resources or the ensuing cross subsidy from self-production of oil to minimise the impact, an uptick of inflation will reduce real growth, income, and consumption with negative consequences for global trade and poverty. The International Monetary Fund is set to reduce the global growth estimates for 2022 below the 4.2 percent forecasted in its February 2022 outlook. In India, the Reserve Bank of India’s estimate of 4.5 percent inflation for FY 2023 could overshoot, though continued volatility and uncertainty in global markets would be the primary constraints for revival of strong growth.

In the poorest economies, sans the fiscal resources or the ensuing cross subsidy from self-production of oil to minimise the impact, an uptick of inflation will reduce real growth, income, and consumption with negative consequences for global trade and poverty.

A definitive disruption in the global economy was clearly not the intended outcome whilst censoring Russia. For one, it pressures the club of oil producers, who have benefited, to share their profits as development support, to buttress investment and consumption levels, thereby, creating opportunities for the incremental “petrodollars” to be profitably invested.

Much depends on the depth of the Chinese support for Russia. Is Russia a convenient, transitory associate or a suitably reliable partner in its quest for global dominance? By the end of this year, President Xi could be as powerful as Mao Zedong was, once the quinquennial National Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) endorses another term for him as Secretary General of the party and thereby Chairman of the Central Military Commission.

A drawn-out conflict cannot be the best outcome for President Putin, Ukraine, or for much of the world. A “Fortress Russia”—cut off from global supply links is at odds with the self-perception of an ascendant Russia. There is little glory in becoming a fossil energy supplier in these carbon busting times. China’s consumption of crude oil has already grown at 5.4 percent per year (versus global growth of just 1.5 percent 2009-2019), to a share of 16.4 percent in global consumption just behind the US at 19.4 percent (2020). Natural gas presents a better future. China’s share of 8.6 percent of global natural gas consumption is still considerably lower than the US’ share of 21.8 percent (2020).

The US nuclear cover and active NATO cover are attractive aspirations for Ukraine, but at odds with the continuing shift in economic and eventually, military power, to Asia.

The average Russian, and now even President Putin, has been shown the limited negotiation room available. Of the four demands put forward by Russia, a neutral Ukraine is the least offensive. The US nuclear cover and active NATO cover are attractive aspirations for Ukraine, but at odds with the continuing shift in economic and eventually, military power, to Asia. Instead, adopting neutrality could be a virtue, for a border state whilst also being practical and future compatible.

Should Ukraine and the other Baltic states wish to hedge their bets and eye China as another guarantor of security against Russian military ambitions, they could usefully revisit the Belt and Road proposals, which have gathered dust since 2019 in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. However, judging from the instinctive Ukrainian response to Russian strong-arm tactics, going cap-in-hand to seek favours doesn’t quite align with the fiercely independent psyche of the Baltic nationalities. Also, a compulsory crash course in the intricacies of Confucian thought might be daunting, though playing a round of League of Legends—China’s most popular multi-player online war game—in the spirit of collaboration might be more welcome.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sanjeev S. Ahluwalia has core skills in institutional analysis, energy and economic regulation and public financial management backed by eight years of project management experience ...

Read More +