-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

It would be strategically and geopolitically prudent for India to extend assistance to Sri Lanka during such trying times.

This piece is part of the series, The Unfolding Crisis in Sri Lanka.

Sri Lanka, a nation of 22 million people, is today facing an unprecedented economic crisis that threatens to undo much of the progress that had been made since the end of the bloody civil war in 2009. Amidst skyrocketing inflation (which stood at more than 21 percent for March 2022), power cuts lasting well over 10 hours, and shortage of essential items—like food, fuel, and life-saving medicines—the crisis appears to have spilled over into newer domains, with the island nation now also confronted with a political crisis wherein so far Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa has resigned amidst violent clashes between pro-and anti-government demonstrators, a caretaker PM been installed, the national emergency declared (including shoot-on-sight orders issued to the military) and dramatic curbs on the use of social media imposed. So, the question that arises is: What are the factors that led to this?

Even though many economists and policymakers point to the pandemic as the principal cause of the problem—linking the fall in earnings from the tourism sector (one of the most significant contributors to Sri Lanka’s GDP) from over US$4 billion in 2018 to less than the US $150 million in 2021 to the drop in the country’s forex reserves—this crisis long been in the making. Between 2009 and 2018, Sri Lanka’s trade deficit swelled from US$5 billion to US$12 billion. In recent years, the economy has had to withstand multiple shocks due to some of the policy measures—drastic tax cuts, downward interest rate revisions, and a ‘disastrous’ plunge into organic farming through a complete ban on imports of all fertilizers and pesticides—adopted by the Rajapaksa government; more recently, it has also had to contend with an unanticipated spike in the import bill caused by inflation on account of the Ukrainian crisis. Amidst all of this, the one event that can be said to have tipped it over the precipice was Sri Lanka’s effective exclusion from the international credit market—caused by a dramatic downgrading of the nation’s credit ratings in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. This essentially made it impossible for Colombo to find the means to service its foreign-currency-denominated debt accumulated over the years, thereby, precipitating the crisis it finds itself in today.

The economy has had to withstand multiple shocks due to some of the policy measures—drastic tax cuts, downward interest rate revisions, and a ‘disastrous’ plunge into organic farming through a complete ban on imports of all fertilizers and pesticides—adopted by the Rajapaksa government.

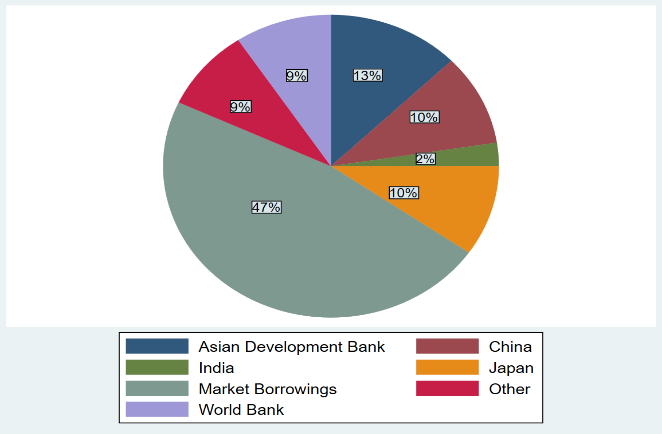

With an outstanding present-day external debt of more than US $50 billion—the largest chunk of it (nearly 47 percent) borrowed from the market, mostly through the instrument of International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs)—and forex reserves of just over US $2 billion (barely enough to foot two months’ import), it appears increasingly unlikely that the country will be able to repay all its debt. In this article, we look at the reasons why India should facilitate a speedy resolution of this crisis and explore some ways it can address the challenges that beset its neighbour.

There are three primary reasons why this crisis affects India: China, trade, and potential political instability.

Even though Sri Lanka occupies an integral spot in India’s neighbourhood first policy, there appears to have been some amount of neglect over the years in fostering closer trade and developmental ties between New Delhi and Colombo, leading to Beijing’s rise as the dominant foreign player in the island nation. This is apparent as China being the country’s top single lender and also its biggest source of foreign direct investment, since at least 2015. Even in trade terms, Sri Lanka imports more from China than India.

India’s concerns about Beijing stem from the very nature of Chinese investment in the island nation and what this could mean in the context of this crisis. Criticised often for being made in exchange for political ‘kickbacks’ and the lack of the required transparency of review and assessment—Chinese investments in Sri Lanka have time and again failed to generate the kind of local employment or revenue expected of them to justify the debt, often compelling the Sri Lankan government to default and thereby surrender strategically-located townships and ports such as the Hambantota in exchange. In many instances, Sri Lanka has simply leased out land in exchange for Chinese investment—for instance, in the case of the Port City of Colombo project where Beijing received over 100 hectares in exchange for a US$1.4-billion investment. Through such means, China has found an increasingly larger territorial foothold in the country. Now, as the economic crisis worsens, Sri Lanka could stand to lose control of even more of its land in such strategically-located port cities. This would heighten Indian fears of greater Chinese presence in this region, given its proximity to some of the busiest shipping routes in South Asia, especially since it considers the island-nation a crucial part of its ‘sphere of influence’.

The figure above gives a break-up of the external debt incurred by Sri Lanka (April 2021). Source: Department of External Resources (website), Government of Sri Lanka.

The figure above gives a break-up of the external debt incurred by Sri Lanka (April 2021). Source: Department of External Resources (website), Government of Sri Lanka.

In more immediate terms, any major disruption to the normal functioning of the Colombo Port due to the crisis would be a source of major concern to India as it handles over 30 percent of India’s container traffic and 60 percent of its trans-shipment. Sri Lanka is also a major destination for Indian exports—receiving over US$4 billion annual worth of merchandise from India. In the event of a worsening of the economic crisis, there would be major implications for Indian exporters who will have to find alternative markets for their produce. Besides trade, India has a substantial investment in the island-nation in the areas of real estate, manufacturing, petroleum refining, etc.—all of which stand to be adversely impacted by the crisis.

Officials estimate that more than 2,000 of such ‘economic’ refugeeld arris couve in India if the crisis were to continue—and this should be a major cause of concern.

Besides trade, investment, and geopolitics, immediate political instability arising out of the current crisis could also become a source of major concern for India. Over the past few weeks, scores of people have fled from Sri Lanka to India. Officials estimate that more than 2,000 of such ‘economic’ refugeeld arris couve in India if the crisis were to continue—and this should be a major cause of concern. For one, any significant spike in the number of refugees could trigger the apprehensions of the state around issues of public safety and refugee resettlement and stoke conflict with the local population over the use of common resources. Additionally, there would be fears of a possible return of the Tamil–Sinhalese conflict (from the days of the Lankan civil war) and its potential spillover into India. It would, therefore, only be in India’s interest to play a role in ensuring a speedy end to the economic crisis.

On the list of countries to which Sri Lanka owes the most debt, India ranks third, behind only China and Japan. It thus has a significant role to play in helping the island nation meet its financial commitments during this time of need. For one, it must consider granting Sri Lanka a moratorium on debt repayment and/or the option of restructuring the debt owed to it. This will not only help Colombo better allocate its limited revenues toward meeting the immediate needs of the people such as food, medicine, and fuel but also go a long way in building some much-needed goodwill amongst its leadership: To be able to counteract, in some way, the influence of enormous Chinese investment over the years. Such a move would assume increased salience amongst the political leadership in Sri Lanka against the backdrop of the recent Chinese refusal of President Rajapaksa’s request to consider the restructuring of its debt. Of course, this should be alongside the developmental and humanitarian assistance that India continues to provide.

Any significant spike in the number of refugees could trigger the apprehensions of the state around issues of public safety and refugee resettlement and stoke conflict with the local population over the use of common resources.

Over the longer term, India must stand ready to provide any assistance required by the island nation. As it is only in India’s interest to reduce Sri Lanka’s dependence on China, the former must contribute to closer integration of the island nation into the world economy. Here, a good place to start would be through expanding bilateral trade between New Delhi and Colombo. The India–Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement (ISFTA), for one, can be utilised to this end. In 2019, only 64 percent of all Sri Lankan exports to India were made under the ISFTA, down from over 90 percent in 2005. On the import side, only 5 percent of all Indian imports were covered under the agreement. This means there is room to renegotiate some of the key inclusion terms of the agreement to spur greater trade-based cooperation between the two countries.

Indeed, at this point, India must do all it can to prevent the crisis from worsening any further.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.