The Internet’s core of key protocols and infrastructure can be considered a global public good that provides benefits to everyone. Countering the growing state interference with this public core requires a new international agenda for Internet governance that departs from the notion of a global public good.

< style="color: #163449;">Internet Governance: Between Technical and Political

Everyday life without the Internet has become unimaginable. It is inextricably woven with our social lives, purchasing behaviour, work, relationship with the government and, increasingly, with everyday objects, from smart metres to the cars we drive and the moveable bridges we cross en route. For a long time, Internet governance was the exclusive domain of a technical community of cyber experts. This community laid the foundations for the social and economic interconnectedness of our physical and digital lives. Those foundations, with the Internet Protocol Suite (Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and Internet Protocol (IP)) as their most prominent component, continue to function as the robust substructure of our digital existence. However, the governance of that substructure has become controversial. The many economic and political interests, opportunities and vulnerabilities associated with the Internet have led governments to take a much greater interest in its governance of the Internet. Moreover, in terms of policymaking, the centre of gravity has shifted from what was primarily an economic approach (the Internet economy, telecommunications and networks) to an approach that focuses more on national and other forms of security: the Internet of cybercrime, vulnerable critical infrastructure, digital espionage and cyber attacks. In addition, a growing number of countries are seeking to regulate their citizens’ online behaviour, for reasons ranging from copyright protection and fighting cybercrime to censorship, surveillance and control of their own populations on and through the Internet. Attempts by nation-states to ‘fence off’ their national area of cyberspace and their increased role in its governance may have repercussions for the Internet’s core protocols and infrastructure.

The Internet was designed to operate internationally, without regard for the user’s status or nationality – an underlying principle that benefits all users. It is mainly the Internet’s public core comprising protocols, standards and infrastructure that routes data so that it reaches all corners of the globe. If these protocols and standards fail or become corrupted, the performance and integrity of the entire Internet will be at risk. The Internet is ‘broken’ if we can no longer assume that the data we send will arrive unaltered and uncorrupted, we can locate the sites we are searching for and those sites will be accessible. Recently, a growing number of states have tampered with the Internet’s core infrastructure to further their national interests.

Internet governance is at a crossroads: the cyberspace has become so important that states are no longer willing or able to regard it with the same ‘benign neglect’ that long set the tone for most countries. States do have national interests that go beyond governance of the Internet as a global collective infrastructure. It is imperative to determine which part of the Internet should be regarded as a global public good – and thus safeguarded from improper interference – and what should be considered a legitimate part of international politics, where nation-states can stake a claim and take up their role without harming the infrastructure of the Internet itself.

< style="color: #163449;">The Internet’s Core as a Global Public Good

The public core of the Internet must be regarded as an impure global public good.<1> As such, it should be protected against interventions of states that are acting only in their national interest, thereby damaging that global public good and eroding public confidence in the Internet. Global public goods provide benefits to everyone, benefits that can be gained or preserved only by taking specific action and by cooperating. The means and methods for providing a global public good may differ from one case to another and can be undertaken by private or public parties or combinations of the two. This can be said to apply to the Internet both as a global network and infrastructure.<2>

The Internet as a global public good is not equated with the whole Internet, or with the sociocultural layer of content and communication. It is applied only to a subset of core protocols and infrastructure. Global benefits derive largely from the Internet’s core protocols, including the TCP/IP suite, numerous standards, the Domain Name System (DNS) and routing protocols.

As a global public good, the Internet works properly only if its underlying values – universality, interoperability and accessibility<3> – are guaranteed and if it facilitates the main objectives of data security, i.e. confidentiality, integrity and availability.<4> It is vital that end-users can rely on the most fundamental Internet protocols functioning properly: those protocols underpin the digital fabric of our social and economic life and existence. Although states will inevitably want to create an Internet in their own image, especially in the sociocultural layer of content, we must find ways to continue guaranteeing the overall integrity and functionality of the public core.

< style="color: #163449;">From Governance of the Internet infrastructure to Governance using it

To highlight the problem, we can use Laura DeNardis’ useful distinction between two forms of Internet governance.<5> The first is ‘governance of the Internet’s infrastructure’, i.e., the governance of the core infrastructure and protocols that drives the Internet’s development. The collective infrastructure takes precedence in this form of governance. The second form is the ‘governance using the Internet’s infrastructure’. In this case, the Internet becomes a tool in the battle to control online content and behaviour – often domestically - as well as a source of threat and a weapon in terms of international security. The issues vary from protecting copyright and intellectual property rights to government censorship, surveillance of citizens, and international intelligence, espionage and military activities online. Increasingly, governments view the infrastructure and main protocols itself as a legitimate means to achieve their policy ends. Whereas Internet governance used to mean governance of the Internet – with the technical management and performance of its infrastructure as the top priority – the trend today is increasingly towards governance using the Internet. Such interventions can undermine the integrity and functionality of the cyberspace and, in turn, undermine the digital lives that we have built on top of it.

< style="color: #163449;">Threats to Governance of the Internet Infrastructure

Governance of the Internet’s public core – i.e., governance of the Internet infrastructure – is entrusted to a number of organisations that are collectively known as the ‘technical community’.<6> Although governance is mostly in good hands, political and economic interests – sometimes combined with new technologies – are challenging the collective character of the community in ways like:<7>

- Economic interests – such as copyright protection and revenue models for data transport – are putting pressure on policymakers to abolish or, conversely, offer legislative protection to net neutrality, which was previously the Internet’s default setting.

- The transition of the ‘IANA function’, which includes the stewardship and maintenance of registries of unique Internet names and numbers. There is currently a transition underway which will remove oversight of IANA from the US sphere of influence mainly for reasons of international political legitimacy.<8> The debate on this transition may result in more politicised management of the DNS, which in turn may have repercussions for the ability to find and locate sites and users. Most countries would benefit from IANA functions that are as ‘agnostic’ as possible, especially when it comes to the administrative tasks.<9>

- The rise of the national security mindset in cyberspace. The technical approach of the CERTs (with a focus on ‘keeping the network healthy’) and their international collaboration is at odds with the approach of national security actors such as intelligence agencies and military cyber commands. It is important to prevent these approaches becoming confused and/or mixed because national security conflicts with the collective interest of the network’s overall security.

< style="color: #163449;">Threats Resulting from Governance Using the Internet Infrastructure

The need for worldwide consensus on the importance of a properly functioning public core of the Internet seems obvious because it is these protocols that guarantee the functionality and integrity of the global Internet. However, recent international trends in policymaking and legislation governing the protection of copyright, defence and national security, intelligence and espionage, and various forms of censorship show no signs of such a consensus. Some states see DNS, routing protocols, Internet standards, manipulation and building of backdoors into software and hardware and the stockpiling of vulnerabilities in software, hardware and protocols (so called ‘zero-day vulnerabilities’) as suitable instruments for national policies focused on monitoring, influencing and blocking the conduct of people, groups and companies. Also, ‘cyber’ is increasingly the part and parcel of international security. Many states have declared cyberspace the fifth domain of warfare and are adding new specialised units to their military and intelligence forces. The negative impact of such interventions is borne by the global collective and impairs the Internet’s core values and operation. Illustrations of this trend include:<10>

- Various forms of Internet censorship and surveillance that use key protocols as well as enlisting the ‘services’ of intermediaries such as Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to block and trace content and users.

- Online activities of military cyber commands, intelligence and security services which undermine the proper functioning of the Internet’s public core. By corrupting standards and protocols, by building backdoors into commercial hardware and software and by stockpiling zero-day vulnerabilities, these actors effectively damage the functionality and integrity of the collective Internet infrastructure and make it less secure.

- Legislation to protect copyright and intellectual property that permits the use of vital Internet protocols to regulate and block content. ‘Side-effects’ of such legislation include the collateral blocking of content and users (overblocking), damage to the DNS and intermediary censorship through ISPs.

- Some forms of Internet nationalism and data nationalism – in which states seek to fence off a national or regional part of the Internet – which require interventions in routing protocols. In extreme forms, this could lead to a splintering of the Internet.

< style="color: #163449;">Challenges for Internet Governance

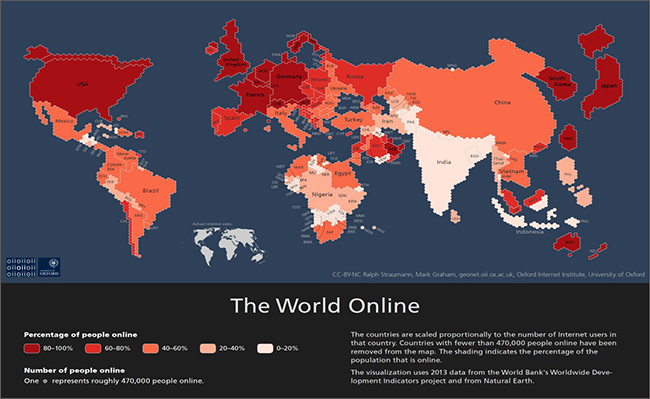

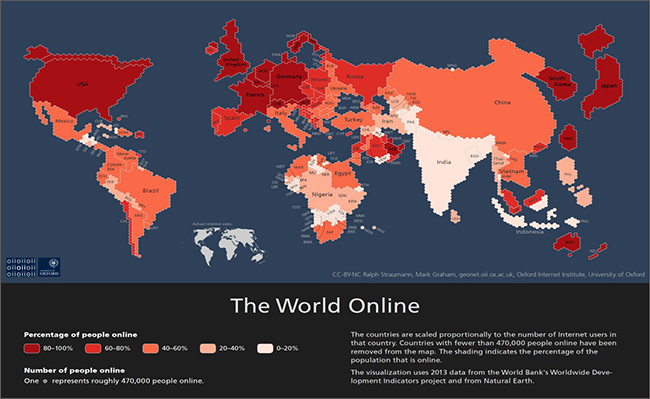

The international political landscape of Internet governance is changing rapidly. The next billion(s) of users will mainly go online in emerging economies that may have a different cultural and political outlook on cyberspace from a still dominant western view. Figure 1 shows the absolute numbers of Internet users globally and highlights the potential for future growth which is especially vast in Asian countries such as India, China, Indonesia and many African and South American nations. In contrast, the West is nearing the saturation point and growth is now more about the number of devices than the number of users.

Source: Graham, De Sabatta and Zook (2015) <12>

Source: Graham, De Sabatta and Zook (2015) <12>

With its growing importance for the economy and high dependence of national (critical) infrastructures on it, more countries will become increasingly active and vocal in debates on Internet governance and cyber security. The global political rift that emerged in the vote on the new ITRs during the 2012 World Conference on International Telecommunications in Dubai indicates that more political contention is likely to emerge in the coming years on both fronts.

Moreover, many countries will have upgraded their technical cyber capacity considerably within a few years, giving a much larger group of states capacities that are currently reserved for only a few superpowers. What is cutting edge today will be much more commonplace in five years’ time. If in that same timeframe – and against this background of international demographic and geopolitical shifts - the idea takes hold that states are at liberty to decide whether or not to intervene in the Internet’s main protocols to secure their own national interests, it is likely to damage the Internet as a global public good. For these reasons, there is no time to lose in securing the public core of the Internet.

< style="color: #163449;">Internet’s public core should be International Neutral Zone

Given these developments, it should be a multilateral priority to work towards establishing a global norm that identifies the main protocols of the Internet as a neutral zone in which governments are prohibited from taking action that damages the public core for the sake of their national interests. This should be considered an extended national interest<12>, i.e. a specific area where national interests and global issues coincide for all states that have a vital interest in keeping the Internet infrastructure operational and trustworthy. With the continuing spread of the Internet and ongoing digitisation, that is increasingly a universal concern.

To protect it as a global public good, there is a need to establish and disseminate an international norm stipulating that the Internet’s public core must be safeguarded against unwarranted intervention by governments.

The starting point should be to place the drafting of such a norm on the international political agenda, something that will entail making governments worldwide aware of the collective and national importance of public core of the Internet. Given the enormous differences between countries in terms of Internet access, overall digitisation and technological capacity, this will require a serious diplomatic and political effort. This norm could be disseminated through relevant UN forums as well as through regional organisations such as the Council of Europe, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the African Union. This strategy could lay the foundations for what could eventually expand into a broader regime.

< style="color: #163449;">Need to Disentangle Internet Security and National Security

The emphasis on national security comes at the expense of a broader range of views on security and the Internet. Defining and disentangling different views on security may in fact improve the security of the Internet as an infrastructure.<13>

It is therefore vital to advocate at the international level that a clear differentiation be made between Internet security (security of the Internet infrastructure) and national security (security through the Internet) and to disentangle the parties responsible for each.

It is of paramount importance to delineate the various forms of security in relation to the Internet. The technical community and the diplomatic/international security community mean different things when they talk about security. The first refer to the security of the Internet as a global infrastructure, or more specifically the notion Internet security, i.e., ensuring that the network itself is secure and operational. The latter usually refer to national and international security, which is mostly defined in geopolitical and military terms. In this vision, the Internet is regarded simultaneously as a source of threat and as a potential policy instrument. For example, it is important to separate the technology-driven strategy of the CERTs, which involves a public health-type approach to the overall network security, from the logic of national security, which places national interests above those of the network. Indications of movement on this issue can be found in the latest report of the UN Group of Governmental Experts (GGE), for example in its argument that states are urged to ‘neither harm the systems and activities of other (national) CERTs, nor to use their own to engage in malicious international activity’.<14> More generally speaking, a more precise demarcation of national security issues from other forms of cyber insecurity would allow more room for the logic of residual risk in matters of cyber security and would apply the logic of national security more selectively to avoid or mitigate escalation.<15> More precise terminology and a clear division of labour between various agencies can in itself function as a confidence-building measure in the international cyber domain.

< style="color: #163449;">Need to Build New Coalitions

Given the international demographic and political shifts in cyberspace, it is time to open, broaden and expand the arena for cyber diplomacy. There is a need to involve states that are still building their technical and political cyber capacities – and occupy a certain middle ground between the multistakeholder camp and the national Internet camp - fully in the debates about Internet governance and international cyber security issues.<16> Secondly, there is a strong case to be made for targeting the large, Internet-based companies as explicit subjects of cyber diplomacy, as well as a need to think through and regulate what the role and position of intermediary organisations on the Internet – such as ISPs and Internet exchanges – is and should be.<17> Finally, states need to make more productive use of the expertise of the technical community, NGOs and other private stakeholders, especially in thinking through the effects of national and foreign policies on the technical operation of the Internet as a whole.

< style="color: #163449;">The Way Forward

Ideas similar or related to the idea of protecting the public core of the Internet have been emerging recently. In January 2016, William Drake, Vint Cerf and Wolfgang Kleinwächter published an excellent paper on the issue of Internet fragmentation for the World Economic Forum.<18> Some forms of Internet fragmentation – those that may have severe, long-term consequences for the functioning of the Internet as a global infrastructure – are akin to the notion of the public core of the Internet. In June 2016 the Internet Society (ISOC) published a beta version of its Policy Framework for an open and trusted Internet in which it states that the technical community shares “a sense of collective stewardship towards the public core of the Internet and the open standards on which its technologies and networks are based”.<19> Also in June 2016, the Global Commission on Internet Governance (the Bildt Commission) published its final report called One Internet, which included a policy recommendation on the protection of the public core that read: “Consistent with the recognition that parts of the Internet constitute a global public good, the commission urges member states of the United Nations to agree not to use cyber weapons against core infrastructure of the Internet”.<20>The Netherlands government issued its formal response to the report on the public core of the Internet in May 2016 and made the protection thereof a long-term priority for its foreign policy on cyber issues.<21> The first port of call to establish a norm protecting the public core will be the 2016-2017 round of the UN GGE of which the Netherlands is one of 25 members. One way forward is to use various diplomatic channels and to create strategic alliances around the idea of protecting the core of the Internet as a global infrastructure to the benefit of all nations and users.

This essay originally appeared in the third volume of Digital Debates: The CyFy Journal

<1>For early thinking on global public goods, see: I. Kaul, I. Grunberg, and M. Stern (1999, eds.) Global Public Goods. International Cooperation in the 21st Century. Book published for the United Nations Development Programme Oxford: Oxford University Press.

<2> As it is technically possible to exclude people from the Internet, economists refer to it as a ‘club good’, i.e. a good whose benefits accrue only to members. Our reference to the Internet’s core as an impure global public good is based on the technical and protocol-related set-up of the Internet with universality, interoperability and accessibility as its core values, which underscore the values of non-rivalry and non-excludability.

<3> See for example L. DeNardis (2013) Internet Points of Control as Global Governance, CIGI Internet Governance Papers no. 2 (August 2013), p.4: ‘With the exception of repressive political contexts of censorship, the Internet’s core values are universality, interoperability and accessibility’.

<4> These are the key aims of data security, also known as the CIA triad; see for example P. Singer and A. Friedman (2014) Cyber Security and Cyberwar. What Everyone Needs to Know, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 35.

<5> See L. DeNardis (2012) ‘Hidden Levers of Internet Control. An Infrastructure-based Theory of Internet Governance’, Information, Communication and Society, 15 (5): 726.

<6>This community includes – but is not limited to - organisations such as the Internet Architecture Board, the Internet Engineering Taskforce and the World Wide Web Consortium that develop protocols and standards and organisations such as the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers and Regional Internet Registries that deal with the distribution of Internet resources such as IP numbers and domain names. Also the global informal community of CERTs or CSIRTs can be considered part of the technical community.

<7> See for a more elaborate analysis of these matters: D. Broeders (2015) The Public Core of the Internet. An International Agenda for Internet Governance. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, chapter 3.

<8> See for example E. Taylor (2015) ICANN: Bridging the Trust Gap. OurInternet.org. Paper series, nr. 9. Waterloo: CIGI

<9> See M. Mueller and B. Kuerbis (2014) ‘Towards Global Internet Governance: How To End U.S. Control of ICANN Without Sacrificing Stability, Freedom or Accountability’, TCPR Conference Paper, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2408226.

<10> See for a more elaborate analysis of these matters: D. Broeders (2015) The Public Core of the Internet. An International Agenda for Internet Governance. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, chapter 4.

<11> M. Graham, De Sabbata, S., Zook, M. (2015) Towards a study of information geographies: (im)mutable augmentations and a mapping of the geographies of information, Geo: Geography and Environment. Vol. 2(1) 88-105. doi:10.1002/geo2.8

<12> See for a definition of an extended national interest B. Knapen, G. Arts, Y. Kleistra, M. Klem and M. Rem (2011) Attached to the World on the Anchoring and Strategy of Dutch Foreign Policy. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 47.

<13> See for a definition of an extended national interest B. Knapen, G. Arts, Y. Kleistra, M. Klem and M. Rem (2011) Attached to the World on the Anchoring and Strategy of Dutch Foreign Policy. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 47.

<14> See paragraph 13(k) of the Report of the Group of Governmental Experts On Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications In the Context of International Security, Report as adopted, Friday 26 June.

<15> For this line of reasoning see: M. Van Eeten and J. Bauer (2009) ‘Emerging Threats to Internet Security: Incentives, Externalities and Policy Implications, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 17 (4): 221-232.

<16> These countries are sometimes referred to as ‘swing states’, see: T. Maurer and R. Morgus (2014) Tipping the Scale: An Analysis of Global Swing States in the Internet Governance Debate, CIGI Internet Governance Papers no. 7 (May 2014).

<17>Broeders, D. & L. Taylor (2016) ‘Does great power come with great responsibility? The need to talk about Corporate Political Responsibility’, in: L. Floridi and M. Taddeo (eds.) Understanding the responsibilities of Online Service Providers in information societies. New York: Springer

<18> W. Drake, V. Cerf and W. Kleinwächter (2016) Internet Fragmentation: an overview. Future of the Internet Initiative White Paper, January 2016. World Economic Forum. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_FII_Internet_Fragmentation_An_Overview_2016.pdf

<19>, Internet Society (2016) A policy framework for an open and trusted Internet An approach for reinforcing trust in an open environment, p. 7. http://www.Internetsociety.org/sites/default/files/bp-Trust-20160621-en.pdf

<20>Global Commission on Internet Governance (2016) One Internet. Waterloo/London: Centre for International Governance Innovation and Chatham House ,p. 75. https://www.ourInternet.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/GCIG_Final%20Report%20-%20USB.pdf

<21>https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2016/05/19/kabinetsreactie-op-aiv-advies-het-Internet-een-wereldwijde-vrije-ruimtemet-begrensde-staatsmacht-enwrr-advies-de-publieke-kern-van-het-Internet-naar-een-buitenlands-Internetbeleid

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: Graham, De Sabatta and Zook (2015)

Source: Graham, De Sabatta and Zook (2015)  PREV

PREV