This article is part of the series—Raisina Edit 2023

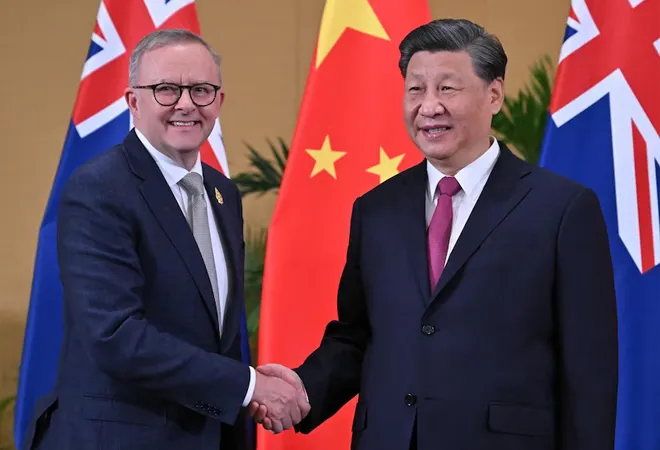

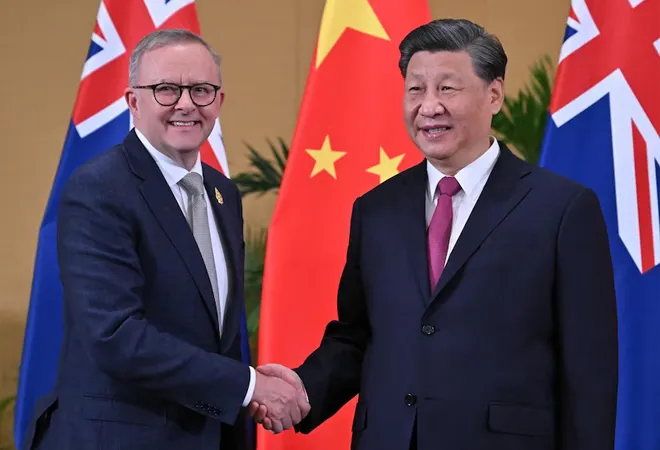

It made headlines around the world when Australian and Chinese leaders met after a six-year gap. But we need to take the right lessons from this thaw in relations. It’s not a turn to China; it’s a return to normality. First, to make sense of developments last year, we need to recognise just how bad Australia-China relations had gotten. Contact that other countries would take for granted had frozen. For example, despite a very challenging relationship, India and China’s leaders meet often, including at the G20, BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and other meetings. There is also regular ministerial contact. For Australia, none of this was happening; In fact, Chinese ministers would not return calls from their Australian counterparts.

< style="color: #0069a6;">Despite a very challenging relationship, India and China’s leaders meet often, including at the G20, BRICS, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and other meetings.

Meetings between ministers for defence, ministers for foreign affairs, and leaders last year is a reversion to the type of relationship other countries have with China, where there are avenues for dialogue and disagreement. Second, Australia has returned to this more normal relationship without “caving in”. Australia has not changed any of its substantive policy positions; for example, on any of the infamous “14 grievances” shared with a journalist by the Chinese Embassy in Canberra, which include foreign investment decisions, banning Huawei from the 5G network, foreign interference legislation, and advocacy on human rights. From the Australian perspective, the new government described its aim as “stabilising” the relationship with China: Stopping the downward spiral in relations and dealing with differences through diplomacy. In the election campaign, it was stressed over and over again that there would be no change of substance in policy on China, only a change in tone. According to Minister for Defence, Richard Marles, “change of tone matters”. Minister for Foreign Affairs, Penny Wong, has made clear that stabilising the relationship occurs within a context where there are real structural differences between Australia and China—in terms of different values and different interests—and that it’s the Australian Government’s job to navigate these differences in the national interest, rather than “to exploit them for domestic political gain”. She describes her aim as navigating differences wisely rather than “trying to make media headlines out of the China relationship.”

< style="color: #0069a6;">In the election campaign, it was stressed over and over again that there would be no change of substance in policy on China, only a change in tone. According to Minister for Defence, Richard Marles, “change of tone matters”.

From the Chinese perspective, the motivation was likely about getting rid of an irritant, particularly as it aims to project a positive face on Chinese foreign policy. The change of government in Australia gave China an opportunity to reset a policy that had clearly been counterproductive as well as negatively affecting Chinese businesses and consumers. The key thing seems to have been the new Australian government’s less confrontational narrative. In the leaders’ meeting, President Xi Jinping told Prime Minister Anthony Albanese that he had noticed him making a “number of remarks on China-Australia relations on a number of occasions, and have repeatedly said that you will deal with China-Australia relations in a mature manner”, implicitly contrasting this with the previous government. Ministerial and leaders meetings were held without any preconditions or changes of position by either side. Third, any further improvements in relations will likely be gradual and incremental. During 2020-2021, Australia experienced import restrictions on a range of goods including lobsters, wine, beef, barley, wheat, timber, coal, and more. These were never admitted by China to be punishment and were justified as sanitary and other measures that just coincidentally hit Australia. Australian exporters hope that the leaders’ meeting will send a message through the Chinese system that Australia is no longer perceived as a hostile country, meaning that lower officials may wave through imports that were previously being blocked. It will also send a positive message to Chinese companies considering investments and parents considering sending their children to study in Australia. There are reports that this is starting to occur, for example, with the first shipment of Australian coal to China in two years. There have been meetings at assistant trade minister level at Davos and, most recently, a meeting of Australia and China’s trade ministers in February with Australia pushing for pathways “towards the timely and full resumption of trade” and China making clear that there are still issues to be resolved. On the security side, many issues remain. In the leaders’ meeting, Prime Minister Albanese mentioned maintaining the status quo on Taiwan, human rights issues in Xinjiang, detained Australians Cheng Lei and Yang Hengjun, and China exercising its influence on Russia over Ukraine. All of these remain unresolved.

< style="color: #0069a6;">Australian exporters hope that the leaders’ meeting will send a message through the Chinese system that Australia is no longer perceived as a hostile country, meaning that lower officials may wave through imports that were previously being blocked.

And in the end, Australia-China relations can’t be separated from deteriorating United States-China relations. There are upcoming triggers that may put pressure on the improved relations. For example, in March, Australia is expected to announce its pathway to acquiring nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS agreement as well as a Defence Strategic Review which sets out Australia’s national security posture. This will potentially cast shadows on further improvement of relations. Former ambassador Kevin Magee thinks the Australian government is committed to no compromise on national security issues. So, looking ahead, what is the trajectory for the future? None of the issues and disagreements that led to the diplomatic freeze have been resolved. The head of the Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney, James Laurenceson, notes that it will not be smooth sailing ahead. He suggests the best way to see the reset is as a return to 2020 rather than to the “sunny days” of 2015. Maybe we can judge the future best by looking at Minister Penny Wong’s visit to Beijing at the end of the year. In some ways, it was entirely unremarkable, just like countless visits by other foreign ministers. The ministers talked about various differences and disagreements. No great breakthroughs were announced, with the biggest announcements being a commitment to “maintain high-level engagement” and “further dialogue” in multiple areas. It showed both sides’ commitment to the long, patient work of diplomacy. This suggests that Australia is back to having a normal relationship with China. One where, in Prime Minister Albanese’s words, “We will cooperate where we can, disagree where we must, and engage in our national interest”. That puts Australia back in the global mainstream.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV