At the 2019 plenary meeting of the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF), Russian President Vladimir Putin reiterated his government’s policy on the development of the Russian Far East (RFE), characterised as a national priority for the 21st century. For this, a separate Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East was set up in 2012 and a presidential envoy appointed to the region. The EEF was subsequently set up in 2015, soon after the breakdown of relations with the West post the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, with the mandate of “economic development of Russia’s Far East and to expand international cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region.”

Since then, it has focused on attracting investment from China, Japan, South Korea, ASEAN and India for the RFE through involvement of their top leadership, ministers and business leaders. India too has in recent years shown interest in expanding its presence here for achieving the twin goals of improving bilateral economic ties and pursuing strategic interests with an eye on China and the broader Indo-Pacific. While the Indian energy companies have had their presence in the region for some time now, a systematic engagement with the EEF began in 2017 with ministerial representation at Vladivostok. In 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, was the guest of honour at EEF.

In August 2019, chief ministers of four states — UP, Gujarat, Haryana and Goa led by the Commerce and Industry minister — visited the RFE to boost cooperation with the region and were accompanied by 140 business representatives. Also, diamond-processing, petroleum and natural gas, coal, mining, agro-processing and tourism have been identified for cooperation in the Far East, by the two countries.

The prime minister’s address at the EEF plenary expressed hope that the 50 business agreements signed between Indian and Russian entities will lead to several billions of dollars of investment. This surge of interest is a welcome development, as Indian businesses explore opportunities in a region seeking economic development. But the challenges the RFE presents remain immense and need to be examined for a full appraisal of the on-ground situation.

Investing in the RFE

The Far Eastern Federal District (FEFD), which covers over a third of the Russian territory and comprises only 5 per cent of its total population, is rich in natural resources, including oil and gas, mineral deposits like diamond, gold, borax, tungsten, and coal. It is also a rich source of hydro-power, fish and other sea food. Despite this, a 2018 World Bank report noted that the Far East is the “least developed region of Russia: It has the smallest Gross Regional Product (GRP) and the biggest territory.” The contribution of the FEFD to the Russian GDP has remained around 5 per cent for almost a decade now.

Source: Federal State Statistics Service (FSSS)

Source: Federal State Statistics Service (FSSS)

The RFE continues to face the challenges of demographic decline, outmigration, harsh weather conditions, concerns about business climate, lack of infrastructure and connectivity. These have been further exacerbated by Russia’s own slowing economic growth rate and the impact of western sanctions. Russia’s inability to become a significant economic player in Asia-Pacific and attract further investment has also been a limiting factor. Its main trading partner here is China, bolstered by energy supplies from Russia.

| Russia’s trade ($ bn) |

2018 |

2017 |

2016 |

2015 |

2014 |

| China |

108.3 |

84.07 |

69.5 |

64.2 |

95 |

| Japan |

20 |

18 |

16 |

20.9 |

30.8 |

| South Korea |

24.8 |

19.2 |

15 |

18.1 |

27.3 |

| ASEAN |

20 |

16.79 |

11.96 |

14 |

22.6 |

| India |

8.2 |

10.17 |

7.71 |

7.83 |

9.51 |

The exports of the FEFD are yet to recover and grow, having slumped in the post-sanctions environment of 2014.

| FEFD |

Exports (US $ mln) |

Imports(US $ mln) |

| 2017 |

22,244 |

6,290 |

| 2016 |

18,640.3 |

5,792.3 |

| 2015 |

20,633.4 |

5,882.8 |

| 2014 |

28,681 |

10,653 |

| 2013 |

28,187.5 |

12,105 |

| 2012 |

25,958 |

10,548 |

Source: Russian Statistical Yearbook, FSSS

The situation with regard to foreign direct investment (FDI) in the region has been even more dissatisfying, with most constituents of the FEFD faring badly in 2019 ratings of attractiveness for investors.

|

Constituents of FEFD |

Rating |

| 1. |

Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) |

20 |

| 2. |

Primorsky territory |

22 |

| 3. |

Khabarovsk territory |

30 |

| 4. |

Sakhalin region |

55 |

| 5. |

Amur region |

64 |

| 6. |

Kamchatka territory |

71 |

| 7. |

Magadan region |

78 |

| 8. |

Chukotka Autonomous area |

80 |

| 9. |

Jewish Autonomous region |

82 |

The regional distribution of FDI in Russia’s regions is heavily concentrated in favour of Moscow and Northwestern Federal district, which together received 78% of all FDI in 2017. In contrast, the FEFD only received 7.5% of its investment from foreign sources in 2017; 90% of which was concentrated in the natural resources sector. The region has struggled to diversify into high-technology products for export. Also, the foreign investment has not translated into a significant rise in the number of enterprises with foreign investment, standing at 2.5% of total enterprises.

After the western sanctions on Russia in 2014, it was hoped that China would fill the vacuum created by the loss of investments from the west. However, those hopes have been dashed and only 2% of China’s FDI in Russia was intended for the RFE in 2017. The Program of Cooperation between Northeast China and Russia’s Far East and Eastern Siberia (2009–2018) also ended in a ‘failure’ wherein only 15 of the 91 projects were being implemented by 2015. The new program signed for 2018-2024 period is low on specifics, raising doubts about its usefulness in leading to development of RFE.

In 2016, Japan accounted for just 0.2 per cent of overall FDI in Russia though the eight-point plan put forward by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2016 which has led to about 200 projects being pursued. By 2018, Japanese investment in Russia had only touched $2 billion, which Putin described as ‘fairly modest.’ By 2019, total South Korean investment in Russia stood at $3.69 billion. FDI from ASEAN too remains at a low level. By 2018, India’s total investments in Russia touched $13 billion. The impact of the $1 billion line of credit would be evident in the coming years.

Foreign Direct Investment in the Russian Federation by ASEAN countries (US $ million)

| Country |

2018 |

2017 |

2016 |

2015 |

2014 |

2013 |

| BRUNEI DARUSSALAM |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| CAMBODIA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| INDONESIA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| LAOS |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| MALAYSIA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

5 |

3 |

| MYANMAR |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| PHILIPPINES |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| SINGAPORE |

1,587 |

2,703 |

15,122 |

185 |

162 |

-502 |

| THAILAND |

0 |

-34 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| VIETNAM |

-128 |

-61 |

1 |

-32 |

-42 |

-29 |

Source: Bank of Russia

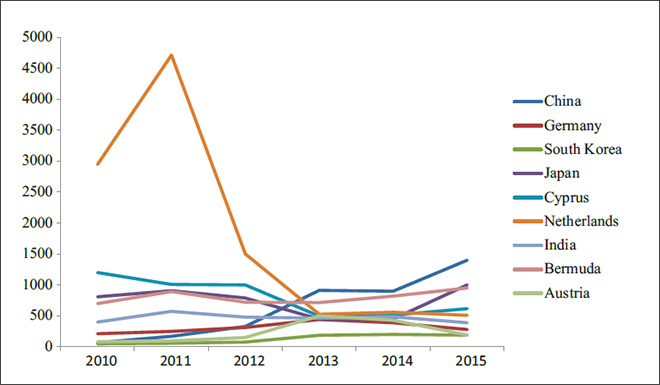

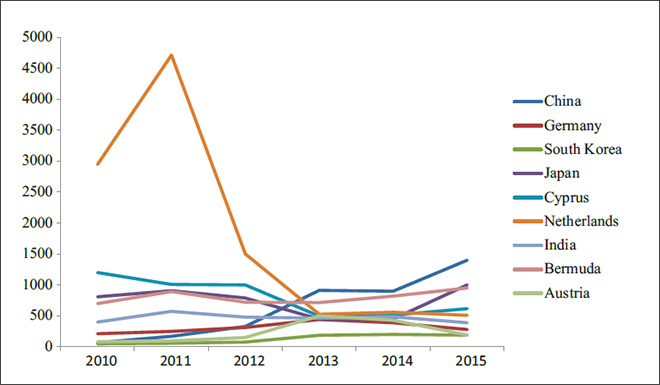

Main sources of FDI in RFE till 2015 ($ million)

Source: Roman Vakulchuk, 2018

Source: Roman Vakulchuk, 2018

This can be accounted for by two factors: one, the RFE is yet to see investment from foreign sources cross 10 per cent of its total investment. This means that a majority of the investment comes from domestic sources. Second, it would take time before western investors like Netherlands, Germany and Austria can be replaced by new actors. In order to given an impetus to investors, the Russian government has established 18 ASEZs to attract foreign investors with tax relief and easy regulatory mechanisms. However, problems of cumbersome bureaucratic procedures and lack of adequate infrastructure have been reported and thus their success remains to be seen.

Conclusion

Based on the above discussion, it can be seen that the Eastern Economic Forum, despite high level visits from countries of the Asia-Pacific, has had limited success in delivering on development of the FEFD. The levels of investment and growth remain far from satisfactory, ensuring that it will be some time before the RFE can be integrated into the more advanced economies of the Asia-Pacific.

Some positive developments have been noted, evident in the region attracting 33% of the FDI being received by Russia in the past years. Putin has noted that regional industrial growth has been three times higher than the national average and outmigration has decreased two-fold as compared to 2005. The EEF has also offered scope for regular interaction with the Asia-Pacific countries, raising possibilities for further cooperation.

The potential opening of the Northern Sea Route, Japan’s introduction of the eight-point plan in 2016, South Korea’s nine bridges approach to Russia under the New Northern Policy, all point to a rise of interest in the RFE. However, the overall regional development and the quantum of FDI has remained low, exacerbated by the shortcomings discussed above, western sanctions and the slowing Russian economy.

In this scenario, Indian government and businesses would do well to carefully examine their prospects. Indian companies currently operate here in areas of diamond cutting, tea packaging, coal mining, oil and gas. Coal and oil constitute 70 per cent of the RFE exports to India. Timber, tourism, healthcare and pharmaceuticals hold potential for future cooperation as well as make a provision for Indian manpower that does not engage in a permanent settlement to make up for labour shortages in the RFE. India would also benefit from collaborating with Japanese and South Korean partners to build trilateral partnerships in the areas of mining, timber and pharma to enhance its presence.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: Federal State Statistics Service (FSSS)

Source: Federal State Statistics Service (FSSS) Source: Roman Vakulchuk, 2018

Source: Roman Vakulchuk, 2018 PREV

PREV