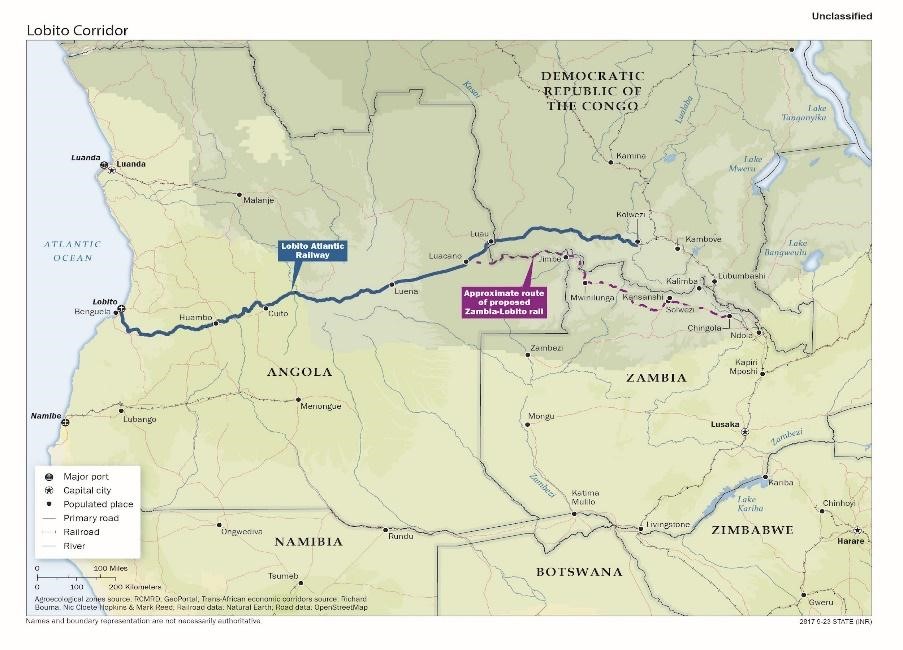

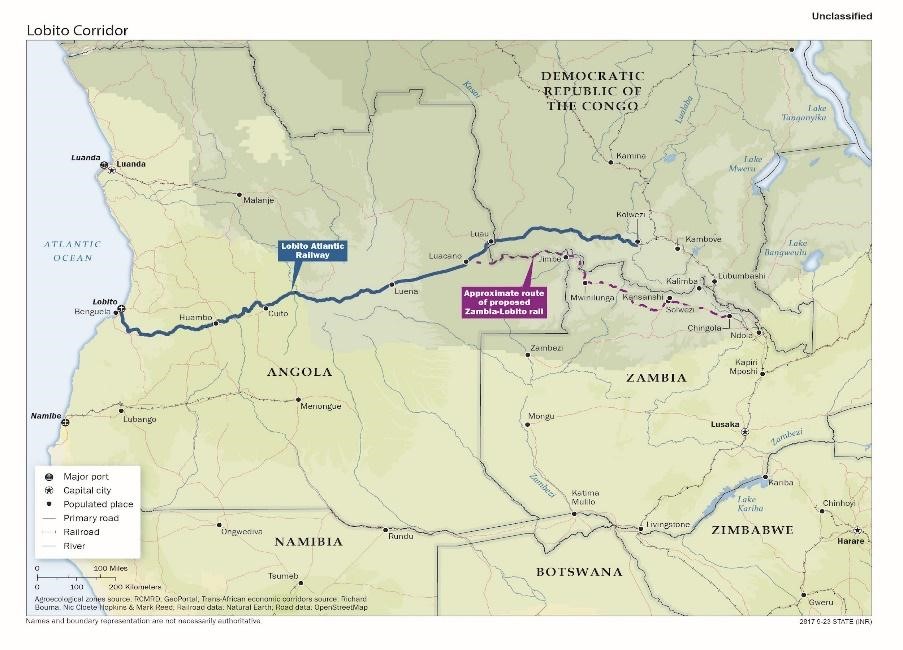

Sitting on troves of unexplored critical mineral resources such as cobalt, copper, and lithium, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Tanzania, and Zambia are emerging as theatres of great power competition in Africa. A new infrastructure undertaking which was conceived under the United States’ (US) Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) initiative—the Lobito Corridor (see Map 1), connecting these three countries, is rapidly emerging as a counter to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in these countries.

Map 1: The Lobito Corridor

Source: The White House

Located in Central Africa, the Corridor proposes to build a railway line connecting the critical minerals mines in Zambia and DRC with the Lobito port in Angola. The project also proposes investments in green energy development, sustainable mining, energy storage to social infrastructure development and public health initiatives. The wide array of economic sectors covered under the PGII’s Lobito Corridor is aimed at presenting a counterweight to Chinese presence in the region.

Beijing is starting this race with an advantage, having built transport infrastructure across the three countries and establishing ‘infrastructure for minerals’ deals, while the US and its Western allies are just catching up.

China’s ‘infrastructure projects for loans and minerals’ strategy

For over a decade, China has pursued a strategy to dominate critical minerals supply chains worldwide through the BRI. It has borne favourable outcomes in Africa. Today, Beijing controls close to 70 percent of industrial cobalt and copper exploration projects in DRC. Besides, it has invested close to US$ 4.5 billion in lithium mining in other central African countries such as Zimbabwe, Angola, and Namibia, between 2018-23. In Zimbabwe, it has committed US$ 1.4 billion for a lithium-processing plant next to a Chinese state-owned lithium mine. Angola possesses 32 out of 51 critical minerals essential for the green transition—to be utilised in electric vehicles, solar panels, windmill generators, and more critical technologies such as advanced chips and supercomputer CPUs. While Beijing’s major energy import from Angola is petroleum, it is also vying for mineral exploration contracts there.

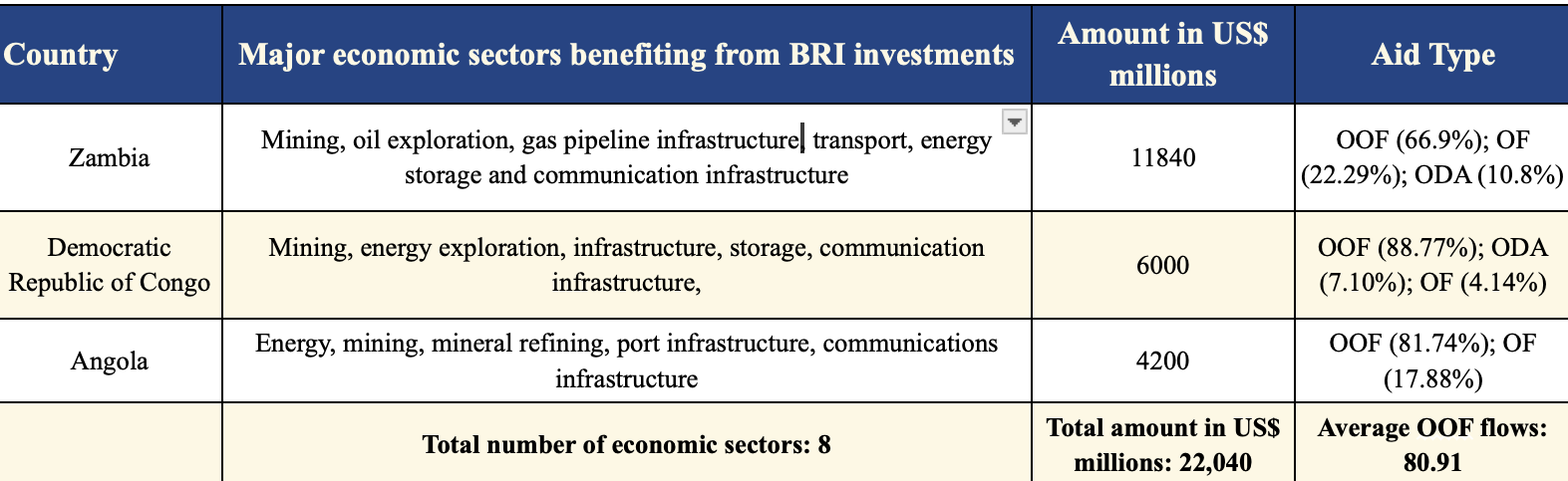

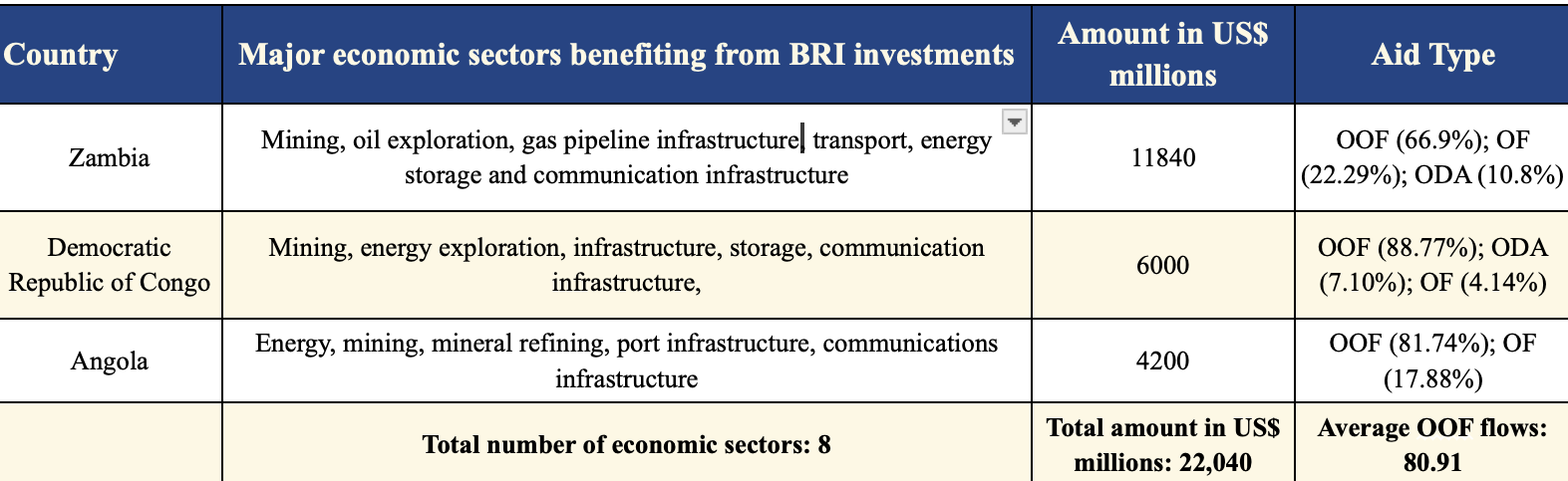

Table 1: Chinese BRI Investments in Central Africa (2013-23)

Source: UNCTAD Investment Reports; External debt departments of the finance ministries of Zambia, DRC and Angola; AidData

As is visible in Table 1, Beijing has invested close to US$ 22.4 billion across various critical economic sectors in Central Africa. Notably, close to 80 percent of Chinese loans and investments in the region flows through the Other Financial Flows (OOF) system, which is not connected to the US-led international financial system, making these cash flows difficult to trace. These investments in Africa have also given China an unmistakable hold over the global supply chains. Its state-owned and private companies dominate 85 percent of global mineral processing and have stakes or full control of over 65 percent of currently active global reserves of the various critical minerals.

Prima facie, Beijing’s model of economic cooperation with Central African countries looks mutually beneficial. Angola, Zambia, and DRC have exported their natural resources in abundant quantities to China since 2006 when China signed an ‘infrastructure for oil’ deal with Angola and in return, built infrastructure across Angola. However, a deeper analysis of this investment model indicates that it has not been a smooth ride for Chinese investments.

The central governments in these underdeveloped nations instrumentalise Chinese credit facilities backed by petroleum or mineral supply guarantees to finance domestic investments. This means that these three countries’ repayment of Chinese investments is tied to their natural resources. However, the value of natural resources has fluctuated as per the global demand, forcing these countries to request Beijing to restructure the debt repayments. Consequently, between 2016-23 Chinese state-owned banks renegotiated or wrote off loans tied to oil and minerals supply in DRC, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Angola to the tune of US$ 21.3 billion.

The promise of Lobito Corridor

The US is now gearing up to counter China’s dominance in Central Africa through the Lobito Corridor. Conceived under the PGII—a transnational infrastructure development programme launched by the G7, the Corridor promises to upgrade infrastructure and connectivity in DRC, Zambia, and Angola.

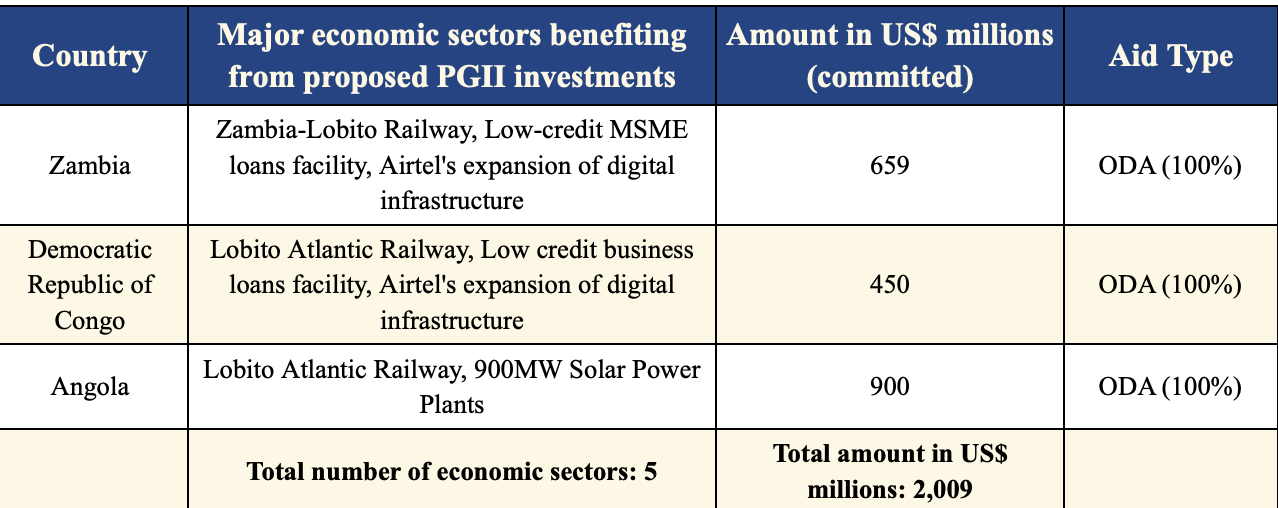

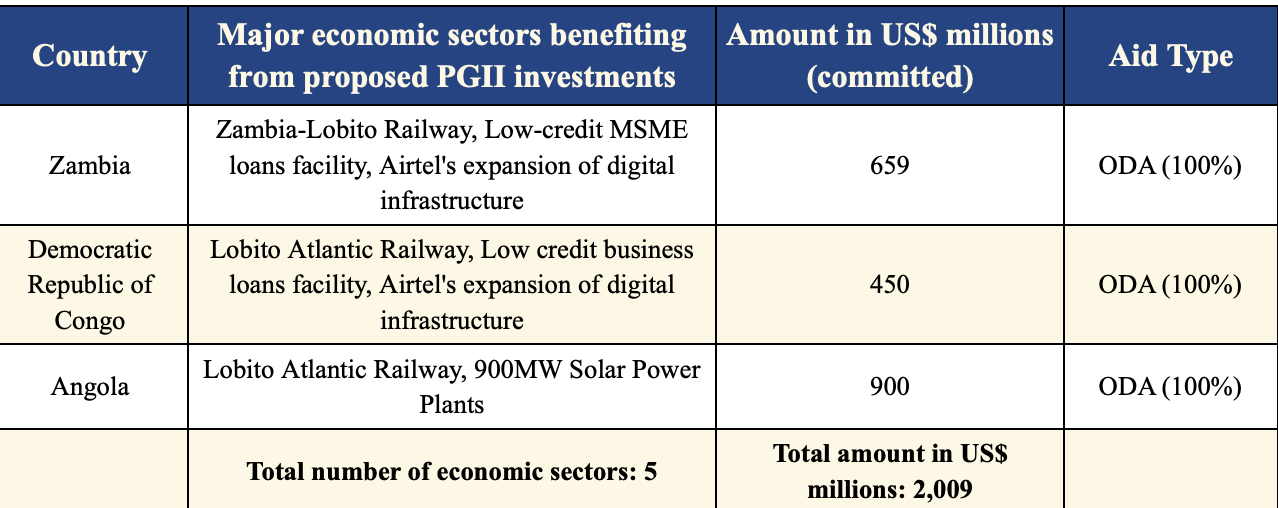

Table 2: Proposed Projects under the Lobito Corridor (2022-23)

Sources: The US PGII Factsheet, The G7 Hiroshima Progress Report, Japan’s Factsheet on the G7 PGlI

As indicated in Table 2, the G7 has committed close to US$ 2.01 billion towards building two green railway corridors—the Lobito Atlantic Railway and the Zambia-Lobito Railway (see Map 1)—across the three countries. These corridors will be laced with digital connectivity projects and green energy infrastructure development. As part of the corridors, private companies from the US and European Union (EU) will build two solar projects with a combined capacity of 500MW, worth US$ 900 million in Angola; the US has also extended a US$ 125 million credit facility to further Airtel Africa’s operations in DRC and Zambia. Moreover, the MoU signed between the US, EU and the corridor nations signals further economic collaboration in critical economic sectors such as mining, energy exploration, public health, education, social infrastructure development and transport infrastructure expansion.

During the recently held premier Global Gateway (GG) Forum and the G20 New Delhi Summit, the G7 partners signed various MoUs with the corridor partners for conducting feasibility studies for the railway line. Moreover, the US and the EU have elevated their partnerships with all three corridor partners to a strategic partnership. The GG Forum also featured a MoU between the consortium of African companies developing the Lobito Corridor and the G7 partners concerning the export of copper and cobalt emanating from the Kamoa-Kakula region, the starting point of the proposed railway line in DRC.

In economic sectors such as social infrastructure and public health, cash flows from the PGII are proposed as official grants.

While the US has also adopted the positive economic reinforcement model, there are certain differences in the G7’s approach to infrastructure development diplomacy. The difference lies in its financing model, debt-repayment structure, focus on sustainability, capacity-building measures and labour relations. PGII investments catalyse economic growth in these countries by synergising already existing low-credit facilities provided by the World Bank Group and African Development Bank with new credit provided by private PGII partners such as the Citi Group. The G7 initiative also provides these countries with critical financial products such as longer tender local currency financing, and long-dated currency and interest rate hedges which are instrumental in attracting foreign investments in developing economies and assisting growth of small and medium enterprises in recipient nations. The G7’s involvement of local companies is also noteworthy and stands in stark contrast to Beijing’s model wherein both—the lender and project contractor (and in several cases the labour employed) were Chinese. Moreover, these investments flow through the Official Development Assistance (ODA) flows, thereby qualifying for concessional interest rates similar to those of multilateral banks, reducing financial pressures on already debt-distressed governments. In fact, in economic sectors such as social infrastructure and public health, cash flows from the PGII are proposed as official grants. As ODA flows, these concessional loans also have a longer grace period and loan repayment timeline as compared to Chinese OOF flows. Moreover, Chinese state mining companies have also come to notice for flagrant flouting and violating international and national mining norms and labour laws in the region.

Conclusion

Yet it is not the first time that the West has come up with a promising international programme to help Africa out of its economic distress. In the previous decades, the continent has witnessed the failed idea of the Washington Consensus, which attempted to reorganise Africa’s macroeconomic policy and direction but ended up exacerbating financial pressures on already distressed African states. This time around the G7 promises to adopt a different approach, having learned lessons from China’s missteps. The PGII is strategically targeting the weak links in China’s infrastructure diplomacy with a focus on sustainability, transparency in financing and investments, capacity building and massive involvement of local companies and populations. To the West as to China, winning the central African states is critical to winning the rare minerals global supply chain race and power the future. What remains to be seen is how efficiently will the G7 and its allies deliver on their PGII promises.

Prithvi Gupta works as a Junior Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV