Since former US President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the United States (US) from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018, the current US President Joe Biden’s attempts to return to the arrangement have faced more headwinds than anticipated. From some angles, the nuclear deal, also known as the

Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), seems unsalvageable. In the immediate setting, Iran’s decision to

remove 27 cameras overlooking various positions inside its nuclear sites in response to a West-supported

resolution submitted to the IAEA threatens to precipitate a crisis which could end efforts to tame Iran’s nuclear ambitions in the long term. Despite

recent European-led attempts to renew talks between Washington D.C. and Tehran, the jury is still out whether it has gone beyond the point of no return from the amount of damage done up until now.

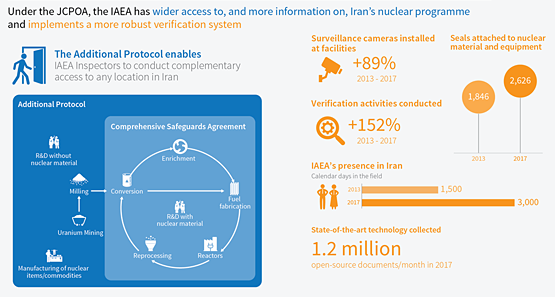

Source: IAEA

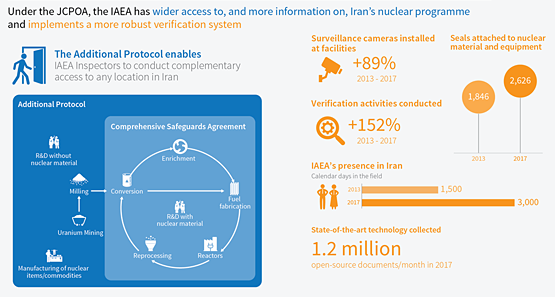

Source: IAEA

Biden’s Special Envoy for Iran, Rob Malley, has highlighted that Tehran has significantly upscaled its infrastructure to build nuclear weapons, contrary to what the deal was designed, and to a certain extent, managed to achieve when it was signed in 2015 amidst equal measure of fefervournd criticism. However, as of today, things stand starkly on the edge. “Iran has been accumulating sufficient enriched uranium and made sufficient technological advances to leave the breakout time as short as a matter of weeks, which means Iran could potentially produce enough fuel for a bomb before we can know it, let alone stop it,” Malley

confided.

Sparring over the JCPOA

Between Tehran and Washington D.C., the main point of contention is the designation of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist entity. In May, Biden decided to keep the IRGC on the terrorism blacklist. This pacified US allies in the Middle East—Israel, Saudi Arabia and even the UAE—all

demanding an increased American security architecture in the region for their protection against Iranian moves. While the likes of Riyadh and Abu Dhabi have been at the receiving end of sophisticated attacks launched by Houthi militants in Yemen, including a long-range drone strike against Abu Dhabi, which

killed two Indian-origin workers, Israel has taken a much more aggressive and existential posture against Iran and the IRGC, more recently reportedly expanding their covert operations inside Iranian territory, targeting its nuclear and military complex. “The gloves are off”, a source close to Israel’s campaign

told The Wall Street Journal. Recently, Iran

dismissed Hossein Taeb, the Chief of the IRGC, reportedly due to the successes achieved by Israel against the country’s defence and nuclear programmes inside Iran.

The nuclear deal was signed under the presidency of Hasan Rouhani, a moderate, amidst significant backlash from the country’s powerful ultra-conservatives who ultimately came to power in August 2021 as Ebrahim Raisi won elections that some observers believe were tipped to his favour.

From an Iranian perspective, a return to the JCPOA domestically is also not as easy a task as many would like to think. The nuclear deal was signed under the presidency of Hasan Rouhani, a moderate, amidst significant backlash from the country’s powerful ultra-conservatives who ultimately came to power in August 2021 as Ebrahim Raisi won elections that some observers believe were tipped to his favour. These conservative voices had previously aired their displeasure in trusting the US, and Trump ended up proving them right. While some believed that a return to the JCPOA could actually be easier under Raisi, as a deal agreed upon by a conservative leader would be more marketable domestically in Iran, the issue of IRGC’s designation created the main contest. For Iran, this remains a non-negotiable point. The contest over IRGC also highlights the dilution of the JCPOA’s original mandate itself, from what was meant to be an arms control regime to one that has become a geopolitical contestation involving various parameters, issues, and grievances.

The complexities of a potential failure of the return of JCPOA are not exclusively bound to the US–Iran dynamic. The deal included significant political infusion from China, Russia, and Europe as well. The first major visit to Iran after the American withdrawal was conducted by China’s Xi Jinping. And despite Beijing’s view of witnessing an opportunity to cement Iran as a long-term ally away from the West, the Chinese do not believe that a nuclear Iran or a nuclear race in the region is beneficial for its own interests. And this is beside the point that Iran’s elites want to be closer to the West. In March, despite the ongoing Russian war against Ukraine, Washington and Moscow, on the sidelines of high-intensity diplomatic friction,

continued to work on revitalising the JCPOA. Even India, which had to cut most of its energy ties with Iran as pre-JCPOA sanctions made the oil trade unmanageable, had used its diplomacy and access to Tehran to market the benefits of the JCPOA for the Iranian economy.

Financially, the Biden administration is constrained by the “Iran Nuclear Deal Advice and Consent Act of 2021,” which restricts any federal funding to advance the JCPOA until President Biden proposes a successor agreement to the Senate for its opinion and advice.

However, despite the international nature of the JCPOA, Biden’s domestic challenges, now heightened further due to the Ukraine war, consume most of his bandwidth. Irrespective of the strong regional security anchoring of the President’s

upcoming trip to Saudi Arabia and Israel, it is the price of oil and inflation in the US that has forced his hand in meeting with Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, despite calling Saudi Arabia a “

pariah” during his campaign period as a presidential candidate.

The view from Capitol Hill

When Biden had

shown his intention to usher America back into the JCPOA early on in his term, it was more about overturning decisions taken by Donald Trump than about the realisation of actual impediments in striking a new nuclear deal with Iran. This realisation gap has widened since, owing to a host of factors. Domestically, for the Democrats securing the approaching midterm elections in November this year has thrown challenges in Biden’s way, limiting his political manoeuvrability. Although the Republicans

lack the number in the Senate to block Biden’s support for reviving the Iran nuclear deal, their political opposition continues. Financially, the Biden administration is constrained by the “Iran Nuclear Deal Advice and Consent Act of 2021,” which

restricts any federal funding to advance the JCPOA until President Biden proposes a successor agreement to the Senate for its opinion and advice. Above all, the chairman of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee has echoed the larger political sentiment in the Beltway by saying that the Biden administration must admit that a return to the 2015 nuclear deal

may not be in the US interest.

This realisation gap has widened since, owing to a host of factors. Domestically, for the Democrats securing the approaching midterm elections in November this year has thrown challenges in Biden’s way, limiting his political manoeuvrability.

Beyond the difficulties that lie ahead for the Biden administration in the domestic political arena, Washington’s challenge remains in keeping regional geopolitics distinctively separate from its core proliferation objectives vis-à-vis Iran. Biden’s upcoming visit to the UAE and Saudi Arabia will pose a challenging backdrop to the JCPOA negotiations, given the former’s tenuous relationship with Iran. Iran will also be mindful of a possible Israel-Saudi Arabia-UAE axis that Biden’s trip might attempt to

forge. While for Washington such a regional axis may help in consolidating its gains from the Abraham Accords and the I2U2, or the West Asian Quad, it can potentially push Tehran to expand its trade and strategic options with partners like Russia and China. Already, China has shown no signs of reducing oil imports from Iran and the Russia-Iran partnership is on an upward trajectory to

circumvent western sanctions as seen by Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s

recent visit to Tehran and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s

phone call with his Iranian counterpart, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian on the same day as Lavrov’s visit, highlights these parallel contours to US–Iran tensions.

Conclusion

As things stand, the fate of the nuclear talks between the US and Iran continues to be guided by a who-blinks-first strategy. The Iranian demands for removing sanctions and safeguards have met the

US insistence that the deal can be negotiated and implemented only if Iran “drops its additional demands that are extraneous to the JCPOA”. However, it is imperative to remember that the JCPOA was a process that involved more than just US and Iran. The other participating parties, including China and Russia despite their differences with the US, would ultimately like to see attempts to reinstate the nuclear deal succeed.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Since former US President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the United States (US) from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018, the current US President Joe Biden’s attempts to return to the arrangement have faced more headwinds than anticipated. From some angles, the nuclear deal, also known as the

Since former US President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the United States (US) from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018, the current US President Joe Biden’s attempts to return to the arrangement have faced more headwinds than anticipated. From some angles, the nuclear deal, also known as the

PREV

PREV