-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

While the Green Deal underscores the ‘whole of EU’ approach, it remains to be seen how the EU can adapt its external efforts to ensure a just transition with the help of just financing

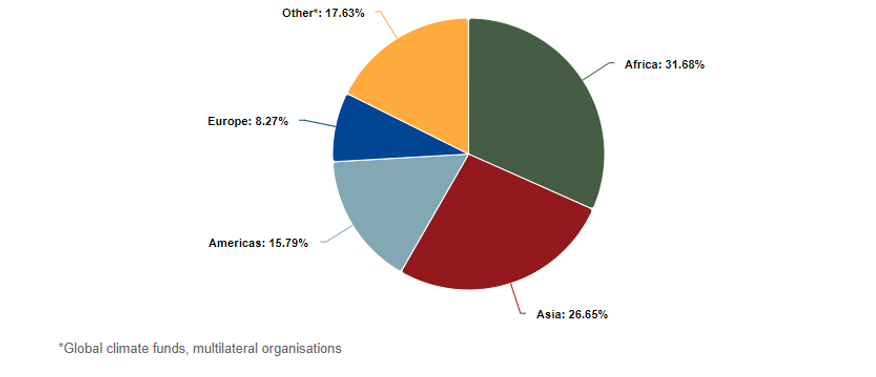

Giving shape to its Green Deal announced in 2019, the European Union (EU) released the Fit for 55 package—a set of proposals and updated legislations to reduce its net greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) by at least 55 percent by 2030—in October last year. Advocating values of democracy, rules-based order, human rights, peace and stability, the EU’s external action is fundamentally influenced by the economic and political clout that it enjoys in different geographies, prominently in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Its external action can be understood by the amount of development cooperation that it has been providing over the years. Collectively, the EU and its institutions with the European Investment Bank (EIB) comprise the largest contributor of public climate finance to developing economies by committing 28.5 billion euros in 2022. Out of this public funding, about 54 percent was allotted for either climate adaptation or cross-cutting action (involving both mitigation and adaptation activities) in the developing regions. Moreover, Africa and Asia are the top recipients of this finance amongst others (Figure 1). Additionally, it mobilised about 11.9 billion euros of private finance during that year for climate change.

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of EU’s climate finance

Source: European Council

However, adaptation financing needs of the developing economies are in dire straits. As per the Adaptation Gap Report, the needs are almost 18 times higher than the current levels of public finance flowing from the developed countries’ kitty. Although they were ‘urged to commit at least double (from the 2019 levels) their collective provision of financing for adaptation by 2025’ at the 2021 Glasgow climate pact, the picture remains grim. The EU Green Deal has three interesting dimensions to it when viewed from a development partnerships perspective. In fact, the context of the deepening geopolitical mêlée makes the Green Deal a bit easier to decipher. As President Ursula von der Leyen emphasised on integrating the domestic interests and foreign policy as two sides of the same coin, the Commission has been shaped with a ‘geopolitical’ bent.

Moreover, the EU has somewhat attempted to showcase European leadership on adaptation. By hoping that its pledge to cut down on domestic emissions will incite other nations to adopt similar ambitious plans is like treading a tightrope. In numbers, the European Commission may have managed to paint a good picture of its financing for adaptation strategy, but the wider EU financing is dismal. In 2020, the EIB invested almost US$ 2.5 billion (i.e., 77 percent) in mitigation in low and middle-income countries whereas only US$ 740 million was cut for adaptation—a meagre 23 percent.

As President Ursula von der Leyen emphasised on integrating the domestic interests and foreign policy as two sides of the same coin, the Commission has been shaped with a ‘geopolitical’ bent.

As ambitious as it could get, the Union through the Green Deal is also looking to aid the initial phase of the green transition by offering funding support for the distributional and social impact of the new EU emissions trading system (EU ETS). Sectors such as transportation, households, and micro-enterprises have been prioritised. Further, it is backed by a social climate fund of 72.2 billion euros to be pumped from the EU budget along with external finance of up to 65 billion euros. However, it is the rollout of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) as a functional option with the existing EU ETS which has created ripples across the developing economies. Hailed by the EU as a stringent measure against curbing ‘carbon leakage’, CBAM has been touted to promote protectionism by levying a carbon cost on imported goods to match with its domestically produced products. Placed at varied tangents of the development trajectory, the Global South naturally finds this as a digression from the EU’s existing narrative of aiding their ‘just transition’.

On the contrary, as a pacifier, the Deal attempts to maintain a balance by utilising the tool of development diplomacy. Many policy ambitions have been elaborated in the Deal focused on developing the needs, priorities and concerns of the partner countries through its external interventions. Here, fostering alliances and collaborations for confidence-building and sharing best practices is underscored. For instance, the Global Gateway initiative offers an avenue for Brussels to finance climate-resilient infrastructure by mobilising 300 billion euros up to 2027. But again, countering its systemic rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is also well noted.

Many policy ambitions have been elaborated in the Deal focused on developing the needs, priorities and concerns of the partner countries through its external interventions.

In such a scenario, global climate leadership has become a question of who can own the narrative of green recovery. However, what the EU needs to do is to embed the Deal in its development cooperation initiatives, both bilateral and multilateral to bolster horizontal transfer of resources, expertise and standards. This would involve addressing the negative spillovers of its regulatory policies, creating policy and fiscal space for adaptation-related thinking, and encouraging development pathways to bring coherence thus, help bridge the North-South divide. A triangular modality of cooperation can unlock pioneering solutions, to begin with. The EU-Morocco Green Partnership signed in 2022 is a relevant example. By giving 50 million euros during the COP28 in Dubai to Morocco, Brussels’ intention is clear as far as forging partnerships in Africa goes, however, clean technology and green energy yet again took the limelight.

In its very essence, as SDG 17 (Partnerships for the goals), development partnerships are grounded in the principles of equality, policy coherence, inclusive growth, and promoting the effectiveness of resourcing strategies. Despite geopolitical factors continuing to influence policies, the EU needs to take on the mantle of closing the gap between an ambitious agenda of the North and the capabilities challenge of the South. While the Green Deal underscores the ‘whole of EU’ approach, it would be interesting to see how the EU can retrofit in its external action to ensure a just transition with the help of just financing as the world seeks to think beyond 2030.

Swati Prabhu is Associate Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Swati Prabhu is Associate Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation. Her research explores the interlinkages between development ...

Read More +