Having seen over four different types of political-systems in the past thirty years, from the communist Soviet invasion to the Mujahedeen, from the oppressive Taliban regime to the fragile democratic state, continuous governmental reform is familiar to Afghans. Today, as the legitimacy of President Ghani’s administration is questioned and the tenants of peace and democracy laid down in 2001’s Bonn agreement crumble in modern-day Afghanistan, the near-future appears politically tumultuous. With the eighth round of US-Afghanistan peace talks underway in Doha, the current possibility of the withdrawal of U.S. troops and the imminent rise of the Taliban means that citizens – particularly women and minorities - must once again learn how to navigate their roles in a new public space. How, then, can women not only survive but thrive in this politically precarious state?

The Georgetown Institute of Women and Peace Security has continuously ranked Afghanistan as the worst place in the world to be a woman, based upon the parameters of inclusion, justice and security. The surface improvements seen in the development of fundamental freedoms and women’s rights over the last eighteen years have to still contend with a mind-set left over from the era of the Taliban regime, a mind-set that in itself is a continuation of medieval times. Moreover, provincial areas are steeped in this past as compared to the more globalised centre of Kabul. The Afghanistan of the 1990’s that saw women completely absent from the public sphere, unable to seek any employment – let alone hold any leadership positions - may no longer exist in the optimistic international imagination but it is still very much a ground reality for most of Afghanistan, specially with the Taliban controlling most of provincial Afghanistan.

Source: Source: ‘Who Controls What: Afghanistan’, Al Jazeera, 24-06-2019

Source: Source: ‘Who Controls What: Afghanistan’, Al Jazeera, 24-06-2019

Leaving aside Kabul, the Western ideals of feminism and freedom have not proliferated into the homes, businesses, or indeed governments, of provinces like Kunduz or Kunar wherein the Taliban wield a considerable influence. To understand any study done on women in Afghanistan, it is thus essential to understand that the capital does not represent the entire country. Mariam Wardak, founder of Her Afghanistan, emphasises the rural-urban divide when saying that sexual exploitation, domestic violence, and a lack of resources is the ground reality in all of Afghanistan, that the situation in 2019 is as bleak as it was in 1999. Of course, on the other hand, the national achievements of the government must not be trivialised - for instance, the new 2003 constitution specifically declares that “The citizens of Afghanistan–whether man or woman–have equal rights and duties before the law,” a sentiment that is missing even from certain first-world countries’ constitutions, including the United States’. The setting up of the National Action Plan for Women in Afghanistan scheme (2018-2018) and the rapid expansion of the operations of the Ministry of Women’s affairs too signal that the (perhaps purely symbolic) fight for women rights is on-going. However, it is clear that these governmental schemes in place are more theoretical than practical - the gender equality that activists, NGOs and citizens have demanded has not been received in full - instead, a watered-down, placatory version that privileges rhetoric over action has been presented to the public. Thus, while fundamental rights today may see a surface improvement, and while the national government may have schemes targeted towards the improvement of women’s rights, the lack of leadership positions available to women in governance or civil society, both in the national and provincial levels, highlights that in practical terms there isn’t too much of a difference between the past and the present.

Women leaders fear a backlash, which means that while their placement in positions of power may serve as inspiration, their impact on women’s rights is negligible, and when women do not support women, how can they expect Afghan men to?

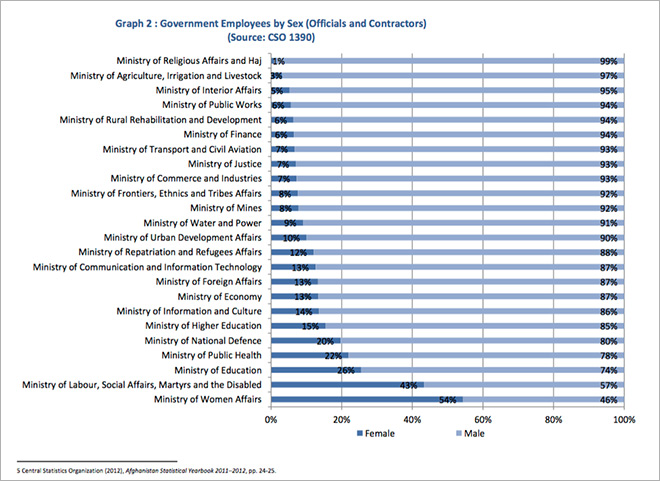

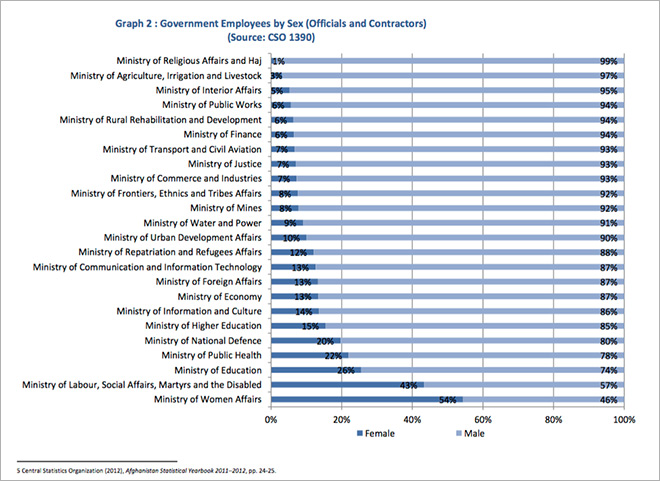

While numbers may not mean everything, statistics do show that today only 22% of women have decision-making roles in governance, 20% in private media, and 24% in community development councils. The quota system that allows this in national governance (the 2004 constitution set a 25% quota for women representatives), moreover, is absent from provincial or regional systems. Success stories, are therefore, few and far between - and often exaggerated and magnified by the Western media. Women in positions of power in the government are purely symbolic, and, as per Wardak, even the superficial gains made by the Afghan government in the last eighteen years are not protected by these women leaders. Women leaders fear a backlash, which means that while their placement in positions of power may serve as inspiration, their impact on women’s rights is negligible, and when women do not support women, how can they expect Afghan men to? The question that therefore arises is that of the impact, or even necessity, of these seemingly ineffective women in what has anyway been termed a ‘puppet regime’. The Ministry of Women’s Affairs, today an established governmental ministry, saw its origins in 1943 under the reign of Zahir Shah. Under the Mujahideen, it was vocational and social in its focus, known as the Women’s General Association and affiliated with the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs. Under the Taliban, the Association was all but disbanded, made up of men rather than women. In 2001, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs came about in its current form, its strategy driven by policy. It is the only governmental ministry that has a higher number of female employees - both in decision making positions (125 as opposed to 92 - 58%) and in overall staff (54%) - than men.

Source: Japan International Cooperation Agency’s Country Gender Profile: Afghanistan 2013

Source: Japan International Cooperation Agency’s Country Gender Profile: Afghanistan 2013

Encapsulating a top-down approach to leadership, women directors of the MoWA fit into President Ghani’s vow to give women more leadership positions in his administration, as does Roya Rahmani, currently the ambassador to the United States of America. Rahmani has stated that women and children are not willing to “go back to the old days” - but when Afghanistan’s gender problem is structural rather than historical, it is clear that “the old days” are still a reality for most women. In a patriarchal and essentially tribal society, the imposition of Western feminism and leadership fits uneasily, superficially. Once the United States withdraws, however, the possible return to the more tribal society does not bode well for the already deteriorating status of women leaders. Even the peace talks being held right now lack women in their midst, with the seventh round even needing to be postponed due to an absence of women and of Afghan officials. If today, with the entire world looking upon Afghanistan and its women, the percentages of women in government remain so dismal (only 23 women hold seats in the Meshrano Jiga which has a total of 102, while only 68 hold seats in the Wolesi Jirga which has a total of 249), it is clear that women are not going to be involved in leading Afghanistan’s future.

The faux feminism of the Afghan Women Network and the Ministry of Women’s Affairs further emphasises the trend of superficial, consolidated leadership that is more for the public eye than the private individual.

The country is, once again, at a transitory point in its history. Its next phase is looking like it will likely see a resurgence of the all-encompassing control of the Taliban, however a metamorphosed Taliban that is being unprecedentedly open about the status of women and women’s rights. However, what the Taliban profess in Doha in terms of peace is at odds with what is seen in the provinces they control, as well as with the surge of violence seen across Afghanistan in the recent weeks. Can a leopard ever change its spots? Or will the whole of Afghanistan soon become a macrocosm of the currently Taliban-controlled provinces, wherein women are still invisible in the public sphere? For Wardak, the future is as bleak as the present - and the past. The symbolic leadership of women currently may see a surge if the rhetoric of the current Afghan government continues, but the operative structure is the real standard to judge - and it’s nowhere near what the numbers depict. The Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) is an index developed on the basis of women’s political and economic participation, including factors like a percentage of seats held by women in parliament, percentage of women legislators, professional workers, and senior officials. Tellingly, the lack of data in Afghanistan, does not allow for the computation of the GEM. However, the Gender Development Index (GDI) calculated on the basis of the standard of living, knowledge, and health and mortality was 0.346 in 2004 - the lowest in South Asia, indicating the highest amount of gender inequality. So, if the numbers themselves are so low, the operative structure - both when it comes to leadership and when it comes to basic development - is dismal. The faux feminism of the Afghan Women Network and the Ministry of Women’s Affairs further emphasises the trend of superficial, consolidated leadership that is more for the public eye than the private individual.

Women leaders in Afghanistan still have a long way to go. The national consciousness of Afghanistan today may acknowledge the existence and even the rights of women but not their potential power. Ms. Muqaddesa Yourish, working at the Independent Administrative Reforms and Civil Service Commission, blames a lack of strong institution for the proliferation of corruption in the country. This very lack of strong institutions is also the missing link for the operative leadership system that Afghan women need, that will be able to protect the fragile gains made in the country so far. It is only when the institutional structures change in Afghanistan, when there are structural changes on a macro and micro level, can the status of women leaders shift from symbols to real people.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV