-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Despite China’s global imprint and its dramatic rise over the last few decades, its intelligence services have managed to avoid global scrutiny. The paucity of information on Chinese covert operations and their objectives remains a challenge for the world considering the many dimensions of contemporary warfare. Chinese Intelligence Services (CIS) have thus far managed to hoodwink the global community and propagate a narrative of supreme secrecy by not subscribing to the general practice of providing a singular representational name or acronym for its intelligence services. Accordingly, analysts have attempted to theorise the CIS to better understand them and to delineate their functions so as to create calculated projections of their evolving stakes and interests.

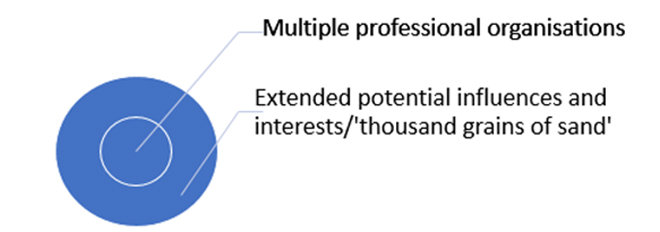

The traditional view holds that the CIS are unlike any other intelligence service since their strategy is based on the ‘thousand grains of sand’ concept. This school of thought essentially proposes that instead of relying on conventional and expensive forms of espionage with professional spies, the CIS rely on multiple avenues of data collection through amateurs which include Chinese businesses, civilians, academics, amongst others, to gather extensive low-quality information which can then be stitched together to form ‘intelligence’. This belief has been criticised for its sweeping generalisations and for misdirecting efforts of other nations in their counterintelligence activities. These critics instead view the CIS as a framework of ‘multiple professional systems’ which function to carry out intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance (ISR) operations both internally and externally. However, since intelligence is loosely described as serving to inform state decision-making, the ‘thousand grains of sand’ metaphor cannot be completely disregarded as information collected could directly or indirectly assist Chinese decision-making.

Notwithstanding these contending viewpoints, while the CIS do essentially follow the pattern of conventional intelligence services with its increasing professionalism and stereotypical espionage activities, China’s authoritarian regime type does indeed provide its intelligence services with a unique facet due to the state’s potential influence in nearly all of its activities. The CIS can be conceptualised to function in ‘concentric circles of operational importance’, with its various professional systems at its core and its other extended potential influence and interests at its periphery. This conceptualisation provides a functional representation of the CIS which prioritises the multiple professional systems for counterintelligence activities while still keeping in the policy calculus the potential influence of an authoritarian state in all of its activities.

Chinese Intelligence Services (CIS) and its concentric circles of operational importance

The CIS core consists of both civil and military agencies. The foremost civil agency is the Ministry of State Security (MSS) with its central ministry, provincial divisions and its many municipal agencies. The MSS focuses primarily on surveying external and internal threats to state security and spying on foreigners to create potential profiles for future recruitment. The Ministry of Public Security (MPS) has internal and external auxiliaries but primarily concentrates on domestic intelligence. The United Front Work Department too has a wide variety of functions and wields influence both externally and internally. In the military intelligence agencies of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the leading intelligence unit is the PLA Strategic Support Force which is responsible for intelligence, technical reconnaissance, electronic warfare, cyber offence and defence and psychological warfare, and also oversees the General Staff Department, and the General Political Department.

At the periphery of the CIS operations there exists a vast variety of areas from which the CIS appears to be gathering intelligence. Among others, these include state media outlets like Xinhua, the New China News Agency which in its charter explicitly notes this intelligence gathering activity. Other organisations like the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office and the Ministry of Education also participate in intelligence activities by maintaining contact with overseas Chinese citizens. The Institute of Scientific and Technical Information of China retains a formal system of collecting foreign technological publications to smoothen the dissemination of knowledge within China. Interestingly, it has been reported that the Chinese state has created incentives for its indigenous businesses to carry out economic espionage in foreign countries. This strategic mobilisation of Chinese assets which were not initially intended for intelligence is warranted by the National Intelligence Law enacted in 2017 of which Articles 7 and 14 explicitly state that Chinese organisations and citizens necessarily have to support state intelligence whenever required. The sweeping nature of this law has been the main reason behind the pushback against the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei.

International reports too shed considerable light on the extent of activities carried out by the CIS. The USA has caught and convicted several Chinese spies who had been mobilised through LinkedIn, an online professional networking platform provided by Microsoft. Interestingly, complementing the ‘great firewall’, which censors data coming into China, is a new system called the ‘great cannon’ which strategically channels an outflow of data from China to targeted locations which can be implemented for malware attacks and denial-of-service attacks. Other instances include an alleged interference reported in 2019 by the Australian media in their political system by the Chinese state which was implicated in providing substantial monetary assistance to an Australian national, who was subsequently found dead, to run for parliament.

The CIS continue to have extensive interests within India, which range from keeping a tab on the development and deployment of nuclear weapons, missile systems, IT capabilities, space and satellite research programmes, and other strategic relationships to mention just a few. Naturally, with their capabilities and spheres of interest, the CIS appear to be not only simply informing decision making, but have also been accused of attempting to manipulate the opponents decision-making, intelligence, offensive counterintelligence, and sabotaging the human and technical sensors of its adversaries. Emerging out of this operative matrix, it can be safely assumed that the CIS has indeed been focusing on India, since even the few operations that have been disrupted and subsequently circulated in the Indian media, remain merely the tip of the iceberg. Indian news reports have mentioned the presence of the core professional systems of the CIS within India at several points with alleged Chinese agents performing traditional espionage activities caught in 2013 and 2018. Furthermore, Chinese reconnaissance ships have been caught spying on Indian assets near the Andaman Island in 2013 and 2019, and during the Malabar trilateral exercises in 2018. In 2019 the PLA’s technologically loaded balloons were allegedly caught spying on India from Tibet.

At the periphery, with more indirect linkages, it is reported that a third of all cyber-attacks in India originate from China. Other reports have cautioned that 42 popular Chinese mobile applications are actively gathering intelligence regarding Indian security instalments. It was revealed in 2010 that Chinese hackers had stolen reports on the Indian missile system as well as emails and other personal information from the Dalai Lama’s office. Apart from this, concerns were raised in 2009 regarding the setting up of 24 Chinese study centres and around 30 firms in Nepal along the Indian border for intelligence gathering and possibly increasing China’s influence in Nepal.

The core of the CIS systems remains at the helm of their coordinated activities and should remain the focal point for counter-intelligence operations. However, the ability of the core systems to mobilise the peripheral support remains a daunting reality for open democratic societies. To reduce this extended ability, actions such as the banning of Chinese mobile applications by the Indian government and the designation of Chinese media firms in the US as foreign missions were perhaps long overdue. These actions seem to originate from the authoritarian institutional framework of China since the trust which was gradually being built since the 1970s has only disintegrated while China’s ability to muster its non-intelligence assets has only been reinforced lately. Democratic societies are having to recalibrate their ties with China in light of the lack of reciprocity which has given Beijing undue advantages.

China’s authoritarian culture has been able to create an intelligence gathering architecture unlike any other, and this lack of a level playing field is a worrying prospect for its adversaries. Past descriptions of China as a ‘panoptic’ or ‘surveillance’ state are increasingly proving to be accurate. For liberal, open and democratic societies it is has now become imperative to understand China’s intelligence system and how it operates so that effective countermeasures can be adopted. As China’s overt aggression generates stronger pushback across the world, Beijing’s reliance on its covert instruments of state power is only likely to grow with serious consequences for international politics.

Anant Singh Mann is a research intern at ORF

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Professor Harsh V. Pant is Vice President – Studies and Foreign Policy at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. He is a Professor of International Relations ...

Read More +

Anant Singh Mann holds aMaster of Science in International Political Economy from the London School of Economics and Political Science and a Master of Arts ...

Read More +