Master plans form the basis for long-term land-use planning for the renewal of cities and urban agglomerations. India’s recent forward-looking urban planning initiatives include the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission, the Smart Cities Mission and the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation. Nevertheless, a 2021 Niti Aayog report states that 65 percent of the 7,933 Indian urban settlements do not have a master plan. As one of the major bottlenecks of Indian planning, almost half of the towns considered urban have the status of census towns<1>.

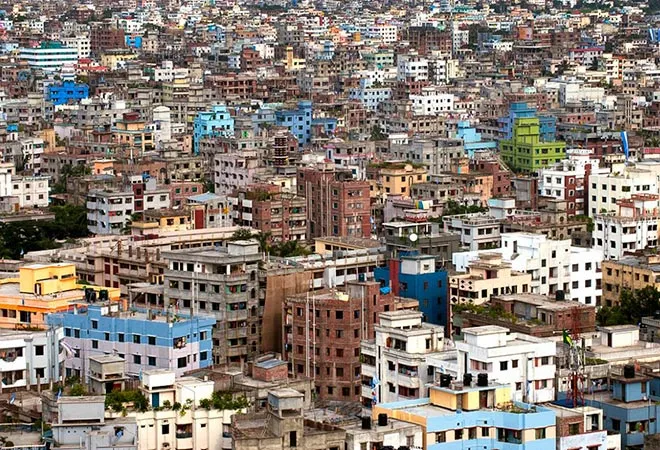

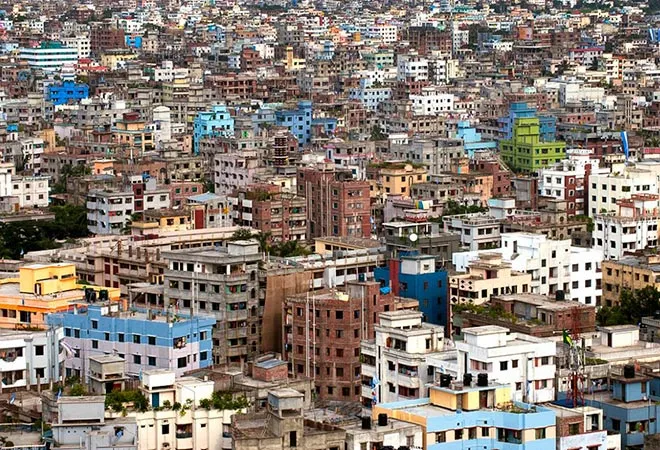

The 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (74th CAA) mandated the devolution of powers to Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) or city governments as the lowest governance unit. State urban planning laws further grant Special Planning Authority status to entities for a notified area, within or outside the jurisdiction of a ULB. Despite these leads, piecemeal interventions and acute gaps continue to mar India’s urban growth. While cities such as Chandigarh and Gandhinagar are exemplary, India’s large metros continue to face haphazard constructions, urban sprawl, drinking water, electricity, and sanitation issues, environmental degradation, and flooding, amongst other issues.

State urban planning laws further grant Special Planning Authority status to entities for a notified area, within or outside the jurisdiction of a ULB.

The concerns may seem commonplace in a nation on the developing curve. Yet, given the size of India’s population, the low quality of urban living calls for a deeper enquiry into the shortcomings of current urban planning and design approaches. As per the 2011 census, 42 percent of India’s financial capital, Mumbai, live in slums blurring the definition of what constitutes the ‘urban’. As a coastal city, Mumbai also bears the destruction of ecosystems and seasonal flooding. Despite its stated focus on affordable homes and job creation, Mumbai’s initial development plan 2034 (DP2034) faced public outcry. The initial DP failed to demarcate the locations and boundaries of its traditional settlements and slum pockets, revealing the shortcomings of the current planning process. Moreover, the DP is amended every 20 years in three stages. Actual implementation takes much longer, by which time existing inhabitants make several land-use alterations. In 2018, Mumbai’s DP2034, for the first time, actively invited suggestions from the public at large. However, the plan’s heavy focus on infrastructure continues to face opposition from various citizen groups and fringe communities, leading to the refrain that public inputs did not find much resonance.

The lack of a participatory approach diminishes even well-meaning interventions. For instance, in Delhi’s Resettlement Programme, squatters of the Sanjay-Amar Colony moved back to live in precarious and unhygienic conditions abandoning their secure resettlement quarters, as the programme failed to take into account their aspirations and needs. Likewise, the camps for farmers’ consent about the second phase of Noida International Airport (NIA) at Jewar face protests for fair rehabilitation and resettlement compensation.

The pattern repeats in city after city, calling into question existing approaches and presenting the pressing need to bridge urban fault lines in a reflexive, participatory, and flexible manner.

Model urban paradigms

Reinforcing that ‘space’ is a limited resource, the UN’s New Urban Agenda deems urbanisation a positive transformative force for people and communities by reducing inequality, discrimination and poverty. Cities such as Singapore, London, Seoul, and Kigali have evolved successful participatory development models, steering a distinct metamorphosis of their urban spaces. A direct comparison may not be entirely appropriate from the Indian standpoint. Yet, analysing these templates can provide frameworks for setting the pace for urban India’s progression and malleability.

Singapore, one of the world’s best-planned cities, reviews its integrated Master Plan every five years, making it flexible to contemporary requirements. The city’s current planning system comprises the Concept Plan with long-term land-use strategies that inform the Master Plan. The plans are reviewed regularly, incorporating public feedback. Singapore’s 2019 Master Plan included multiple local engagement strategies via public exhibitions, focus group sessions, community workshops, and stakeholder meetings.

The London plan likewise involves citizens in local area planning, which builds into the larger regional plan giving importance to aspects such as social infrastructure and heritage conservation. Public involvement in borough planning builds a sense of ownership and responsibility amongst residents leading to the cost-effective and sustainable growth of neighbourhoods. The borough’s plans are seamlessly aligned to the London Plan with the overall strategy of urban renewal through an integrated city planning system.

The living area plan accounts for smaller geographical units to balance development between regions and sub-regions through governance and citizen participation.

Similarly, Seoul follows a three-stage plan that places citizens at the centre: Urban master plan, living area plan, and urban management plan. As an intermediary, the living area plan accounts for smaller geographical units to balance development between regions and sub-regions through governance and citizen participation. Though not statutory, it became a critical addition focusing on peoples’ day-to-day life, including transport, education, leisure, and recreation. The 2030 Seoul Plan themed “Happy Citizens’ City with Communication and Consideration” addresses five core areas and 17 action points. Citizens’ Groups and sub-committees which shape and implement Seoul’s vision include experts, planners and members of the civil society.

On the other hand, Kigali’s transformation from a conflict zone to a safe capital within two decades delivers an ideal template for greenfield planning approaches. Kigali’s Master Plan offers Flexible Zoning Plans shrinking the number of commercial and residential zones. Its mixed-use developments align with the concept ‘Our Kigali’, inspiring participatory city-making as a ‘City for Citizens’ and preserving its local identity. Apart from developing the Central Business District, its plan underlines redevelopment for restoring existing structures.

Even ideal plans and well-governed models cannot deliver if they are not participatory, inclusive, and contextual. As one of the most sustainable models, the Brazilian provincial capital of Curitiba was famed for its innovative planning approach—a unique mass transport system, systematic lane-planning, large public parks, grass fields to combat flooding, and advanced waste management practices. Yet, Curitiba’s inability to integrate the aspirations of its different regions coherently led to non-sustainable on-ground practices significantly diminishing expected outcomes.

Lessons for India

India’s growing urban crisis goes against the spirit of the constitutional right to live with dignity. Approaches remain over-standardised, plagued by implementation glitches with key concerns specific to regions and communities often unaddressed or under-addressed. While legislations such as the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition Rehabilitation & Resettlement Act, 2013 and the 74th CAA offer several creative solutions and promote a participatory approach, their implementation has been tardy. Even in those cases where public participation was solicited, they have remained perfunctory, with little follow-through activity and a lack of accountability. This erodes trust in the participatory process, as exemplified in the events post Mumbai’s DP2034. Replacing intermittent processes with result-oriented public participation, where substantive outcomes follow suggestions, is central to creating a trustworthy and sustainable co-creation model. Cumbersome traditional approaches need to be replaced with cost-effective ones that allow greater transparency and accountability.

Equitable land and sea use must resonate with the needs of citizens, reflecting contextual ground realities. India’s cities, characterised by rich culture and heritage, often face dissonance by the top-down imposition of technical, spatial plans. Homogenous and static approaches in the case of highly stratified societies such as India may not be able to present solutions for a heterogeneous urban mix. A case in point is the Bus Rapid Transit system, which has not been successful in most cases, despite public transport usage by the majority.

Successful global models illustrate how urban transformation must go beyond optimising land-use and zoning rules and the importance of intensive community engagement and feedback as integral to the planning process.

Replacing intermittent processes with result-oriented public participation, where substantive outcomes follow suggestions, is central to creating a trustworthy and sustainable co-creation model.

Master plans must prioritise vigour and community well-being through sustainable and integrated frameworks. While infrastructure and mobility are essential, there must be a balanced emphasis on quality of life, access to basic facilities and everyday needs such as jobs, housing, education and healthcare towards more humane urban designs. The success of the civil society-driven Versova Koliwada makeover project in Mumbai offers a good local template in this regard. The project gives fisher communities the ownership to rethink their coastal habitats. As a bottom-up approach, this project is driven by community feedback interlinking the sea and livelihoods with economies, creek, solid waste management and climate change.

Adopting theme-based models with clear focus areas may have merit in the Indian context while considering the specific development needs of different cities. It is, however, crucial to avoid delays in the overall development process and include comprehensive response mechanisms with shorter deadlines.

Indiscriminate planning drains precious public money and cannot be easily undone. It also has cascading consequences on subsequent development, resulting in a continuing breakdown. The biggest challenge in making cities resilient is building mutual faith between planners, policymakers, and citizens to develop and implement an urban plan with a shared vision. These resolutions will come from going beyond urban aesthetics and fusing diverse views within the city’s social, political, cultural, and economic fabric. Multi-stakeholder approaches can cultivate, enhance, and restore India’s cities to be simultaneously competent, attractive, adaptable and socially inclusive, providing opportunities for future growth and enabling a fulfilling life.

<1> a census town is one which is not statutorily notified and administered as a town, but nevertheless whose population has attained urban characteristics.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV