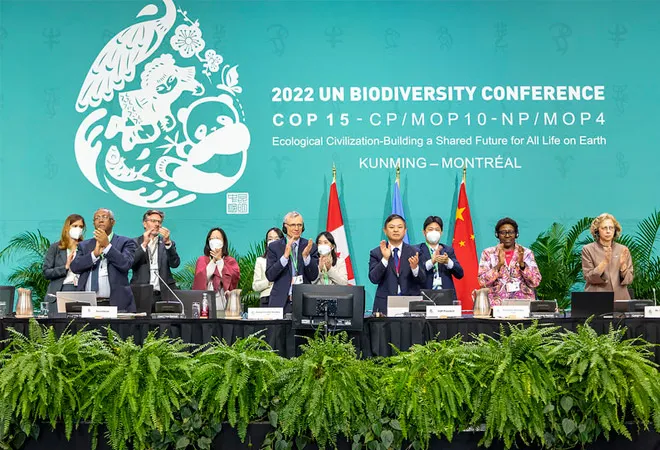

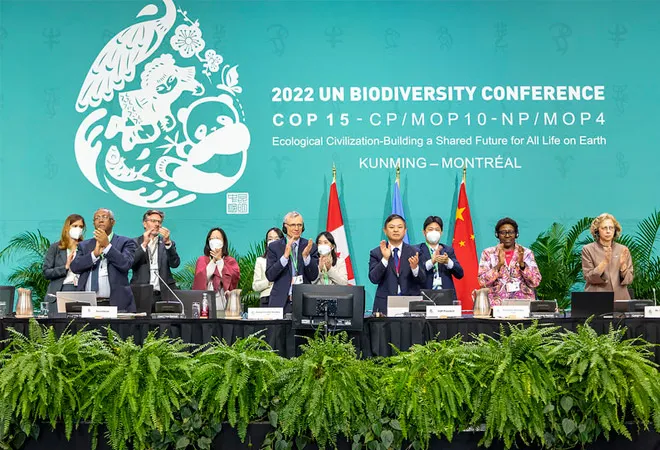

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted in December 2022 by the 15th Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has been held as a ‘historic and monumental’ framework for nature and people. The Framework comes at a juncture when biodiversity loss is accelerating due to industrial, extractive, and infrastructural activities, and is therefore aimed at halting and reversing biodiversity loss and putting nature on a path to recovery for the benefit of the planet and people. To do so, it has laid out four major goals and 23 targets to support the achievement of these goals. It also signifies the recognition of indigenous people and local communities’ rights to land and resources, includes the protection of environmental and human rights defenders, and includes gender equality by recognising women’s role in biodiversity conservation.

The Framework comes at a juncture when biodiversity loss is accelerating due to industrial, extractive, and infrastructural activities, and is therefore aimed at halting and reversing biodiversity loss and putting nature on a path to recovery for the benefit of the planet and people.

The success of the global targets set out in the Kunming Montreal Protocol would, to a large extent, depend on the operationalisation and implementation by nation-states. Therefore, it needs to be closely watched and monitored at the national level. Of particular importance is Target 3, popularly referred to as 30x30, which seeks to conserve and manage 30 percent of terrestrial and inland water and marine as well as coastal areas till 2030. This target is meant to build on the Aichi Targets set at the Conference of Parties in 2011. The thrust of this target is towards increasing Protected Areas (PAs) and Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs).

India’s progress?

It is interesting to note that India has reported that it has effectively brought 22 percent of its terrestrial area and 5 percent of its marine and coastal areas under the Protected Area Network, reportedly through the declaration of ‘Protected Areas’ as per six categories: National Parks, Wildlife Sanctuaries, Conservation Reserves, Community Reserves (under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972); Reserve Forests, Protected Forests, and Village Forests (as per Indian Forest Act, 1927); Lakes and Water Bodies (as per Wetland (Conservation and Management) Rules, 2017) and Biodiversity Heritage Sites (as per Biological Diversity Act, 2002). Earlier this year, the Union Minister of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change stated that, in the coming years, more areas will be brought under conservation and the 30x30 target will be “comfortably achieved” by 2030.

India has recognised all ‘reserved forests’ (officially reported as more than 442,000 ha as of February 2022) as part of its ‘Protected Area Network’. But what does it mean for “reserved forests”, a legal category of forests under the Indian Forest Act 1927, to be declared as PAs? If we consider this Act, its preamble states that it consolidates the law relating to ‘…forests, the transit of forest-produce and the duty leviable on timber and other forest produce’. Thus, reserved forests under this Act are clearly not created with the legal intention to protect or conserve but rather the creation of a forest estate for revenue generation. This category, therefore, has no biological basis, and large tracts of land have been legally classified as reserved forests without there being any ‘forest’ cover on these areas.

Two protected areas were completely de-notified, namely Galathea Bay Sanctuary and Megapode Sanctuary, which are both in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and form a part of the Important Marine Protected Areas of India.

Further, what does it mean for these areas to be ‘protected’? In a press release in December 2021, the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change reported that the PA coverage steadily increased from 4.90 percent in 2014 to 5.03 percent in 2021. However, according to a report by Legal Initiative for Forest and Environment, in the year 2021 alone, the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL) diverted (or converted for non-wildlife use) more than 1,000 ha of PA land out, of which nearly 800 ha was from tiger reserves. These diversions were for infrastructure projects like roads, railways, transmission lines, pipelines and canal projects, mining, quarrying, irrigation and hydel projects. Out of these, two protected areas were completely de-notified, namely Galathea Bay Sanctuary and Megapode Sanctuary, which are both in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and form a part of the Important Marine Protected Areas of India. Another report by the Centre for Financial Accountability states that from August 2014 to February 2019, the NBWL cleared 682 out of the 687 projects in and around PAs for diversion. This is a staggering rate of approvals.

The other way in which Target 3 is pushing for conservation is the emphasis on recognising ‘Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures’ (OECMs) defined as, ‘A geographically defined area other than a protected area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio–economic, and other locally relevant values’. The concept of OECMs was brought into CBD discussions by indigenous people and local communities to highlight the conservation value of landscapes that were their customary territories, to counter the exclusive conservation model of creating ‘human-free’ protected areas; the long-term vital issues of tenure insecurity and lack of access of local communities to their traditional conserved areas and their wanton destruction and diversion for extractive purposes.

India has identified 14 categories of OECMs under the broader categories of terrestrial, water bodies, and marine ecosystems over sites including privately managed areas owned by single individuals; municipal corporations; corporations (involved in manufacturing fertilisers, vehicles, etc); foundations and trusts and land managed by nature clubs; Biodiversity Management Committees and some local panchayats and villages, which is classified as government-owned land; or deemed and unclassed forests. The efforts towards protecting these landscapes by such institutions are laudable and cannot be written off.

Take the Aarey area in the heart of the bustling metropolis of Mumbai where parts of the landscape that adjoin the Sanjay Gandhi National Park were given to the dairy development board, the municipal corporation, and several real estate projects over the years.

Many of the proposed OECMs identified by India are areas conserved by citizen-led initiatives born out of threats posed to these landscapes. India’s first OECM—the Aravali Biodiversity Park in Gurugram, for instance, was a stone quarrying site before it was restored by some citizens. They have fought against plans to have a highway constructed in the landscape. One can think of several such citizen-led initiatives in and around urban and semi-urban areas as well as rural landscapes that are of very high conservation value and are being threatened due to various nefarious activities. Take the Aarey area in the heart of the bustling metropolis of Mumbai where parts of the landscape that adjoin the Sanjay Gandhi National Park were given to the dairy development board, the municipal corporation, and several real estate projects over the years. Concerned citizens from around the area as well as scheduled tribes have been protesting against illegal tree felling by the municipal corporation to build a metro car shed in the area. The Aarey area is a rich, diverse forest ecosystem but remains to be finally classified as a legal forest category. Another instance is the Degrai Oran in Rajasthan’s Jaisalmer. While the deliberations over the draft of the framework were taking place in Montreal, the villages that use and protect this Oran were on a yatra against large-scale renewable energy transmission power lines that are blocking and killing the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard and other birds as well as the region’s camels.

Such areas are ideal OECM and their classification as such should be able to recognise the conservation importance of the area as well as provide effective safeguards for local conservation efforts. However, in India, the current process of declaration of an OECM is entirely voluntary, in addition to the fact that the recognition of an area or landscape as an OECM will not have any legal, financial, or management implications. What this means is that while India will be able to ‘report’ such areas as being conserved landscapes, they will not be protected from diversion for any other non-conservation activity.

The implementation of these targets, therefore, needs to be critically examined through actual actions of nation-states to protect and conserve areas of biodiversity importance and not just the reporting of percentages of implementation. This will have to be done by empowering indigenous people and local communities, and by governments taking special interest towards legally safeguarding such areas from destructive activities.

Meenal Tatpati is a Senior Research and Advocacy Associate with Kalpavriksh Environment Action Group

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV