This article is a chapter in the journal — Raisina Files 2023.

This article is a chapter in the journal — Raisina Files 2023.

Beginning in late March 2022, as Sri Lanka experienced its worst economic crisis yet, over a hundred self-organised and creative protests spread across the country.

<1> In the weeks preceding the protests, Sri Lankans battled power cuts that lasted over half a day and soaring prices of food and other essentials as inflation reached 25 percent in only a few months.

<2> People stood in queues for many hours to purchase fuel and gas; at least four elderly people died of heat exhaustion in that chaos.

<3>

Sri Lankans then took to the streets demanding the resignation of the president at that time, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, and the relinquishing of power of the entire Rajapaksa family. Slogans echoed— “GoGotaHome”, “GoRajapaksaHome”, and “GoHome225”—demanding an end to nepotism in government and the resignation of Cabinet Ministers.

<4>

In April, all 26 Cabinet Ministers resigned, with 42 MPs deciding to function as independent Members of Parliament. The Government quickly fell to a simple majority with only 114 MPs, turning the economic meltdown into a political crisis.

<5> This was followed by Mahinda Rajapaksa stepping down as prime minister in early May 2022 amidst violent clashes between pro-and anti-Rajapaksa camps.

<6>

The Gotabaya Rajapaksa government tried but failed to quell the protests—it declared a state of emergency, imposed island-wide curfews, and deployed security forces. Finally, the protesters stormed and occupied the President’s House and the Prime Minister’s Office, demanding the resignation of leaders. Gotabaya, elected in 2019 with an overwhelming majority, fled the country.

<7> Upon Gotabaya’s official resignation on 14 July 2022, lawmakers, from a secret ballot, chose Ranil Wickremesinghe as the elected Executive President.

The events brought back into focus, earlier discourse on China’s debt trap in Sri Lanka. Ever since the Western media reported on Sri Lanka’s leasing the Hambantota Port to China for 99 years as a case of debt-to-equity swap, Sri Lanka had become a poster child for the ‘Chinese debt trap’ narrative. While it was not the first time that Sri Lanka was dragged into a global discussion on China’s growing role as a capital exporter, the Western reportage was pivotal. When the economic crisis hit the island nation in 2022, the debate resurfaced.

<8> Following Sri Lanka’s sovereign debt default in April 2022 with China being the largest bilateral creditor, the impact of Beijing’s lending on Sri Lanka’s crisis gained the spotlight.

Yet, Sri Lanka’s economic crisis is far more complex than indebtedness to China. To begin with, China is not the largest contributor to Sri Lanka’s rising external debt servicing requirements. However, the increase in servicing in loans from China has been significant over the years, making Beijing an important stakeholder in Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring measures.

In this backdrop, this article attempts to unravel Sri Lanka’s economic crisis and explore both, Beijing’s role and domestic policy failures. It shows what role China has played in Sri Lanka as a bilateral creditor and how this has evolved over the years, and offers lessons for countries facing similar debt distress.

Unpacking Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis is a culmination of multiple economic and political factors that had simmered over decades.

<9>,<10> Indeed, the country has been experiencing macroeconomic instability and economic stagnation and was suffering from a twin deficit problem—in balance of payment and foreign exchange reserves—due to years of economic mismanagement and corruption in government.

<11>

Its failure to attract foreign direct investment after opening up in 1977, the civil war that created a volatile business environment for investors, and a lack of policy consistency by successive governments—all have resulted in an import-led economy that was deep in debt, in turn resulting in balance-of-payment problems and a foreign reserve deficit. Successive governments’ populist economic policy decisions tied with populist electoral policies and favouring reciprocal relationships between the bureaucracies and the wealthiest, led to an unhealthy balance between government revenue collection and gross domestic product (GDP). A combination of tax exemptions and reduced tax collection granted to wealthy people, multinational corporations, and local businesses resulted in a steady decline in tax revenues beginning in the 1990s.

<12> As of 2021, the tax revenue amounted to only 9.6 percent of GDP, against expenditure close to 20 percent of GDP. Poor revenue performance resulted in a decline in the government’s expenditure-to-GDP ratio and called for deficit financing.

<13>

Limited access to concessional loans from bilateral and multilateral partners as a result of graduating to a middle-income country forced Colombo to go to international capital markets for commercial borrowings to finance its needs, especially in infrastructure. Consequently, the debt-to-GDP ratio, which had declined by 2009, steadily increased by 2014.

<14> Constant domestic and external shocks since 2018 did not help, either. The political crisis in 2018, where then President Maithripala Sirisena sacked then Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, the Easter Sunday attack in 2019, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022—caused direct and indirect impacts on the economy.

Perhaps the final nail in the coffin were continuous policy missteps and less-than-desirable economic management of the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government. The Value Added Tax (VAT) cut from 15 percent to 8 percent, resulting in Sri Lanka being downgraded to a ‘substantial risk’ investment category in 2020, closed doors to international financial markets. As the COVID-19 pandemic impacted exports, remittance and tourism revenues, as Colombo had to continue servicing its debts without earning dollars, and as imports continued to balloon—Sri Lanka’s forex reserve decreased at a rapid rate. A ban on chemical fertilisers in the guise of shifting to organic agriculture, backfired overnight when it affected the agriculture yield, ultimately resulting in food shortages. The tea industry, one of the main sources of foreign exchange, saw its yield plummet by half.

<15> The rise in the global fuel market due to the Ukraine war compounded the challenges. The result was a sharp decline in government revenue, a dramatic dip in government reserve, and an increase in imports.

Continuous shortages in essentials, including food, medicine and fuel, hyperinflation and prolonged power outages, forced the government to default on its international payments in April 2022. After ignoring calls from experts to seek IMF assistance, Sri Lanka began negotiating a bailout in April 2022. On 12 April 2022, whilst negotiating, Sri Lanka

temporarily suspended its foreign debt payment as a preemptive measure. About a month later, in mid-May 2022, Colombo missed the 30-day grace period of repayment, making a ‘preemptive default’ for the first time in history, leading Fitch to downgrade Sri Lanka as a ‘restrictive default’.

<16> The new government under President Ranil Wickremesinghe is seeking an IMF bailout to secure a US$2.9-billion assistance to be released over four years to help the flailing economy.

<17>

Sri Lanka’s Debt Story with China

Prior to the early 2000s, China’s role as a creditor to Sri Lanka was minimal. While China accounted for approximately 10.1 percent of the country’s public debt in the mid-1970s, its lending significantly declined in the following years. As such, China’s debt profile in Sri Lanka at the end of the 1990s was merely 0.3 percent. Official aid loans provided by China were on interest-free basis, with long maturity periods and adequate grace periods. Since then, there has been a dramatic evolution of China’s role, and today it is Colombo’s largest lender and development partner.

<18> China’s debt composition in Sri Lanka moved from 0.3 percent to 16 percent between 2000 and 2016. By the end of 2022, China’s debt stock in Sri Lanka had reached some US$7.3 billion, amounting to 19.6 percent of Colombo’s public external debt. These figures include debt recorded in Central Bank and state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

<19>

According to Muramudali and Panduwawala (2022), China’s role as a lender to Sri Lanka evolved in four distinct phases, from being purely a bilateral lender to a project-based lender, and finally to a balance of payments supporter.

<20> The first phase, between 2001 to 2005, began with China lending US$72 million through China Exim Bank for the state-owned Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC). It was the first time that China introduced China Exim Bank (ChExim) as a lending agency. The loan was obtained in 2001 to finance the Muthurajawela Oil Tank Farm project. It was a loan with interest payable, carrying a maturity of 20 years and a grace period of five. This phase also introduced Chinese construction companies such as CHEC and China Metallurgical Corporation to develop infrastructure projects.

During the second phase, between 2007 and 2010, there was a boom in disbursements from China, and Beijing’s role changed from being a small, predominantly non-commercial lender to a large-scale commercial lender embarking on high-profile infrastructure financing. ChExim provided loans, including export or buyer’s credits, for high-profile infrastructure projects such as Norochcholai Coal Power Plant, Hambantota Port, Mattala Airport and Expressway network, some of them at high interest rates.

<21> Even so, the average public debt interest rate for Sri Lanka at that time was only at 3.1 percent, and therefore still affordable.

<22>

The third phase occurred between 2011 and 2014, when the Sri Lankan government borrowed greater amounts from ChExim to expand mega infrastructure projects, and for some new transport sector projects including railways, expressways, and rural roads. This phase coincided with China introducing its flagship Belt and Road Initiative, and some of the projects were included under the BRI umbrella. It also coincided with the end of the grace period on principal repayments of some of the loans obtained during the first and second phases, resulting in an increase in the principal payments from 2013 onwards.

After a slowdown in disbursements between 2015 and 2016, a fourth phase began in 2017. At this time, Sri Lanka was already showing signs of debt distress due to borrowings at the international capital market and its debt stock piled up. As the island nation’s Balance of Payment became increasingly vulnerable, its foreign debt repayment continued to rise, and export performance stagnated. China then emerged as a lender of both project financing and budgetary financing. While the ChExim provided disbursements for infrastructure projects, China Development Bank (CDB) provided a US$1-billion Foreign Currency Term Financing Facility (FCTFF) as direct budgetary financing in October 2018. Since then, China has continued to provide FCTFF regularly as BOP support for Sri Lanka, allowing debt inflows from China to remain higher than the rising debt service payment to them. Credit facilities obtained from China have helped Sri Lanka strengthen its foreign reserves at a time when Colombo’s public debt-to-GDP ratio was at an all-time high, and is left with little option but to borrow further for investment purposes. FCTFF provided during the subsequent years have helped tide over external financing during the pandemic period.

Is China the Problem?

Contrary to popular belief, however, it was not Chinese debt alone that entrapped Sri Lanka in debt. More recent scholarly research has discredited the so-called ‘Chinese debt trap’ argument. Even though Beijing’s debt stock in Sri Lanka has increased, the debt problem was not made in China.

<23> As Chatham House notes, the borrowing from China in the BRI period only saw a modest rise from its pre-BRI period.

<24>

Sri Lanka’s debt problem is created primarily in the international capital market in the West due to the government’s excessive borrowings at commercial rates. According to recent calculations by Sri Lankan economists, the country’s outstanding public external debt stood at US$40.654 billion as of end-2021. Of this, US$37.615 billion was borrowed by the Central Government and guaranteed SOE debt.

<25> Its public debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 91 percent to 119 percent between 2018 and 2021.

<26> As of the end of March 2022, its external debt service payments per year were at US$6 billion, whilst its foreign reserve was only US$1.9 billion.

<27>

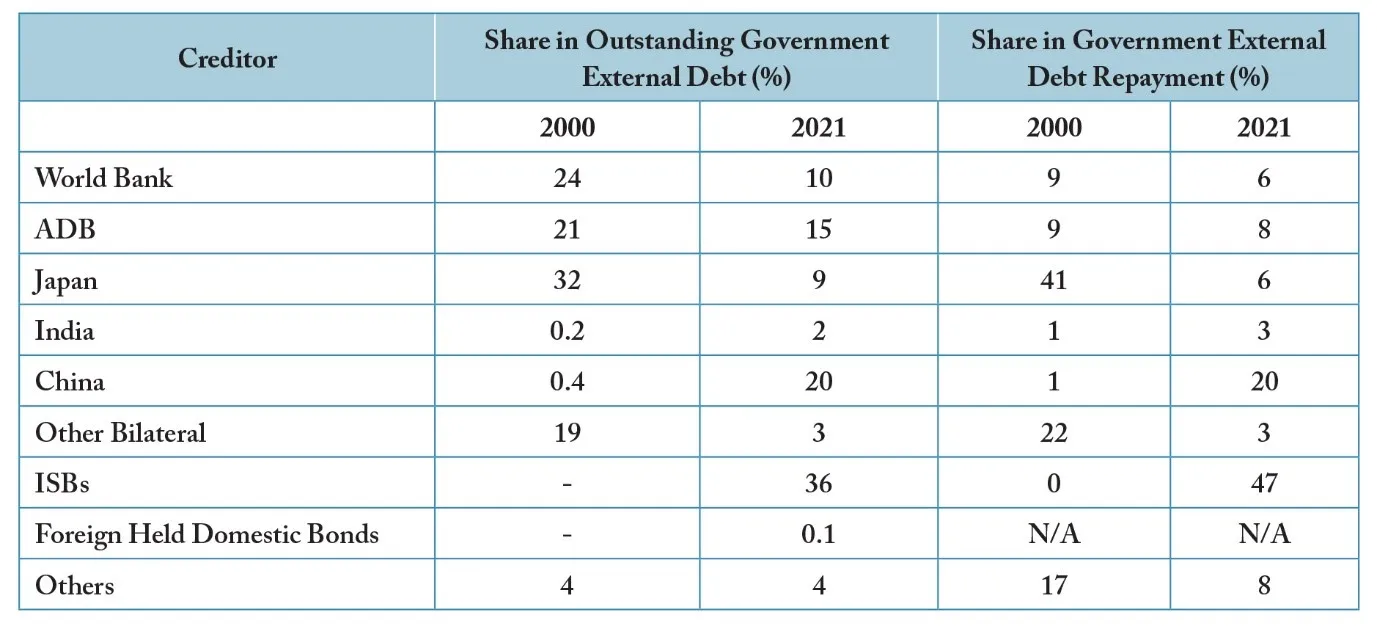

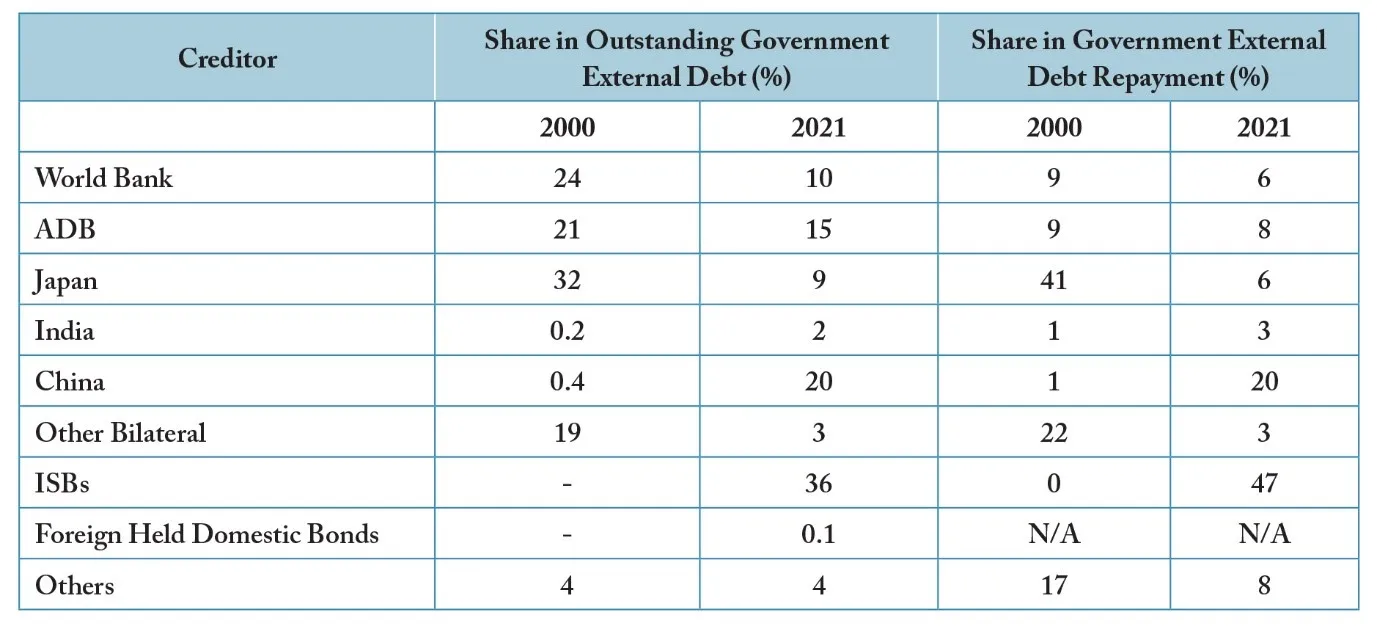

Table 1. Sri Lanka’s External Debt Stock (2000 and 2021)

Source: Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022)<28>

Source: Moramudali and Panduwawala (2022)<28>The main driver of Sri Lanka’s debt problem is the increase in the dollar-denominated international sovereign bonds (ISBs) or Eurobonds borrowed from the international capital market. As of the end of 2021, the share of Sri Lanka’s ISBs is US$13 billion, or 35 percent of total government foreign debt.

<29> In 2021, Sri Lanka repaid US$1 billion in principal and a further US$934 million in interest for the ISBs—47.5 percent of the government’s external debt servicing that year, and twice the debt to China. Moreover, there was no immediate issue for Sri Lanka in servicing Chinese loans, nor was the lease of Hambantota port an equity swap as it has been perceived by the international media. The loan for the Hambantota Port is still being serviced by the Sri Lankan government and is recorded under the Treasury, after moving it from the books of the Sri Lanka Port Authority (SLPA).

<30> Thus, China’s role in making Sri Lanka a debt-ridden country is exaggerated.

Lessons to Learn

China’s complicated debt story in Sri Lanka provides some useful lessons for other debt-distressed economies. It offers insights into China’s nature as a lender in times of debt distress.

Despite being a latecomer, China today is the world’s largest sovereign creditor in overseas development finance.

<31> Two of its banks, the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (ChExim), together provide as much international development finance as the next six biggest multilateral lenders combined.

<32> It is also a player that uses a different rule book than other bilateral lenders. As a result, China follows less stringent procedures for disbursing its finances. Unlike Japan or other members of the Paris Club, China does not conduct its own due diligence before providing sovereign credits and is available for every kind of project. This has allowed borrowing countries to obtain loans quickly and use them for any project. While this has made China an attractive lender to developing nations, this very quality is now proven to have serious implications for international debt management.

Sri Lanka’s story shows that even though China is lenient in its lending policies, it is not so when the borrowers cannot adhere to the repayment arrangement. In general, China does not respond well to requests for debt restructuring. Sri Lanka previously sought Chinese support to restructure its debt in 2014 and 2017, but both requests were dismissed.

<33> In 2022, when Sri Lanka made the same request as the crisis unfolded, and as Colombo defaulted on its debt, Beijing’s response was lukewarm. As a result, Sri Lanka’s efforts to begin an IMF programme have been delayed. At the time of writing this article, Sri Lanka’s other creditors are awaiting China’s call on the debt restructuring process.

This reveals that no matter how good a political relationship a country has with China, it cannot expect an immediate response during a time of debt distress. China’s delayed response could be due to several reasons. For one, China is a newcomer to the system and is inexperienced in overseas lending.

<34> It is equally inexperienced in debt restructuring. It has continuously dismissed Western-led rules and norms in the past for ideological reasons. Yet now Beijing has learnt that such norms and practices exist to protect both the lender and the borrower. Thus, China is buying time to understand the system and find ways of responding to the new developments strategically.

<35> At the same time, as the world’s largest sovereign credit holder, China may want to be careful to not set a precedent in its lending practices.

<36> As the entire world is going through a recession, a large number of its debtors are going through debt distress. Unilaterally granting a debt moratorium for Sri Lanka would set a precedent for having similar negotiations with other debtors. This has put China in a strategic dilemma.

Meanwhile, it is to be noted that debt restructuring in China is a complicated process. Multiple Chinese financial institutions have provided loans to Sri Lanka, and these institutions have their own processes and make their own decisions.

<37> ChExim and CDB—the two largest banks that have provided loans to Colombo—operate in different ways. Moreover, the debt profile varies as Sri Lanka has borrowed both commercial and concessional loans, with the concessional loans having lower interest rates and subsidised by the Chinese government. In this context, a greater consensus within and between the banks and other financial institutions will require China to formulate an acceptable debt restructuring process for all. Similar consensus would also be required between China, other bilateral creditors such as India and Japan, and ISB bondholders. China’s past behaviour in debt restructuring with countries like Zambia and Ecuador has shown that it prefers getting preferential treatment.

<38> However, all the other creditors would prefer to be treated with equity relative to each other.

Finally, China’s equation with other creditors will play a significant role in succeeding debt restructuring efforts. China has a complicated relationship with Sri Lanka’s other major bilateral creditors, i.e., India and Japan. Their political complications will likely play out in the negotiation table. This will not only delay Sri Lanka’s debt restructuring but will also affect future bilateral relations.

In conclusion, Sri Lanka’s debt issue is a result of the country’s weak macroeconomic policies and its high dependency on commercial borrowings and export credits to finance its twin deficit problem. China’s role in this debt story is complicated and controversial. While China may not have created the debt problem, it has a crucial role in resolving it. The way China would respond will set precedence for addressing the debt distress of emerging markets.

Endnotes

<1>Thilina Walpola, “

The Art of Dissent: The Aragalaya Showcased the Most Creative Form of Protest,”

The Island, August 28, 2022.

<2> Deutsche Welle, “

What’s behind Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis?,”

The Indian Express, April 2, 2022.

<3> Keshini Madara Marasinghe, “

Economic Crisis in Sri Lanka and Its Impact on Older Adults,” Oxford Institute of Population Ageing, May 5, 2022.

<4>“

Photos: Sri Lanka Protesters Defy Curfew after Social Media Ban,”

Al Jazeera, April 3, 2022.

<5> Chandani Kirinde, “

Gota’s Govt. Hangs onto Simple Majority in Parliament for Now,”

Daily FT, April 6, 2022.

<6> “

Mahinda Rajapaksa Steps down as Sri Lankan Prime Minister amid Economic Crisis,”

The Indian Express, May 9, 2022, ; Alasdair Pal and Uditha Jayasinghe, “

Sri Lanka Protesters Call for New Government a Day after Clashes Kill Eight,”

Reuters, May 11, 2022, sec. Asia Pacific.

<7> “

Sri Lanka: Protesters ‘Will Occupy Palace until Leaders Go,’”

BBC News, July 10, 2022, sec. Asia.

<8> Ananth Krishnan, “

‘Entrapment’ or ‘Ineptitude’? Sri Lanka Debt Crisis Reignites Debate on Chinese Lending,”

The Hindu, May 7, 2022, sec. World.

<9> Chulanee Attanayake, “

Years of Policy Failure and COVID Throw Sri Lanka into Deep Crisis,”

East Asia Forum, April 24, 2022.

<10> Vagisha Gunasekara, “

Crises in the Sri Lankan Economy: Need for National Planning and Political Stability,” Institute of South Asian Studies, November 23, 2021.

<11> Chulanee Attanayake and Ganeshan Wignaraja, “

Sri Lanka’s Simmering Twin Crises,”

The Interpreter, August 26, 2021.

<12> Gunasekara, “Crises in the Sri Lankan Economy”

<13> Yougesh Khatri, Edimon Ginting, and Prema-chandra Athukorala, “

The Sri Lankan Economy: Charting A New Course, Chapter 2 Economic Performance and Macroeconomic Management,” ADB, 2017.

<14> Gunasekara, “Crises in the Sri Lankan Economy”

<15> Joanik Bellalou, “

Photos: How Sri Lanka’s Forced Organic Transition Crippled Its Tea Industry,”

Mongabay Environmental News, October 1, 2022.

<16> Peter Hoskins, “

Sri Lanka Defaults on Debt for First Time in Its History,”

BBC News, May 20, 2022, sec. Business.

<17> “

Unprecedented economic and political crisis mark 2022 in Sri Lanka; India’s assistance provides breather,”

The Print, December 30, 2022.

<18> Attanayake, Chulanee, and Archana Atmakuri. “

Sri Lanka: Navigating Sino-Indian Rivalry,” in

Navigating India-China Rivalry: Perspectives from South Asia, C. Raja Mohan and Jia Hao Chen, eds., 67–77. Singapore: Institute of South Asian Studies, 2020.

<19> The figure is little higher than often quoted 10% of the total. However, it is to be noted that this is because of the complexity in Sri Lanka’s recording of debt stock. For more information see Umesh Moramudali and Thilina Panduwawala, “

Evolution of Chinese Lending to Sri Lanka since the Mid-2000s - Separating Myth from Reality,”

Briefing Paper, no. 8 (December 28, 2022); Umesh Moramudali and Thilina Panduwawela, “

Demystifying China’s Role in Sri Lanka’s Debt Restructuring,”

The Diplomat, December 20, 2022.

<20> Umesh Moramudali and Thilina Panduwawala, “

Evolution of Chinese Lending to Sri Lanka since the Mid-2000s - Separating Myth from Reality,”

Briefing Paper, no. 8 (December 28, 2022).

<21> Moramudali and Panduwawala, “Evolution of Chinese Lending to Sri Lanka since the Mid-2000s”

<22> Umesh Moramudali and Thilina Panduwawala, “

From Project Financing to Debt Restructuring: China’s Role in Sri Lanka’s Debt Situation,”

Panda Paw Dragon Claw, June 13, 2022.

<23> Dushni Weerakoon and Sisira Jayasuriya, “

Sri Lanka’s Debt Problem Isn’t Made in China ,”

East Asia Forum, February 28, 2019.

<24> Ganeshan Wignaraja et al., “

Chinese Investment and the BRI in Sri Lanka” (Chatham House, March 2020).

<25> Moramudali and Panduwawala, “Evolution of Chinese Lending to Sri Lanka since the Mid-2000s”

<26> International Monetary Fund, “

Sri Lanka: 2021 Article IV Consultation-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Sri Lanka,” IMF, March 25, 2022.

<27> Central Bank of Sri Lanka, “

Presentation by the Governor of the Central Bank Ajith Nivard Cabraal at the All-Parties Conference on 23rd March 2022,” March 28, 2022.

<28> Moramudali and Panduwawala, “Evolution of Chinese Lending to Sri Lanka since the Mid-2000s”

<29> Moramudali and Panduwawala, “Evolution of Chinese Lending to Sri Lanka since the Mid-2000s”

<30> Saliya Wickremesuriya, interview by Chulanee Attanayake, December 1, 2022.

<31> Jue Wang and Michael Sampson, “

China’s Approach to Global Economic Governance from the WTO to the AIIB,” Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank, December 2021.

<32> Robert Soutar, “

China Becomes World’s Biggest Development Lender,”

China Dialogue, May 25, 2016.

<33> Umesh Moramudali and Thilina Panduwawela, “

Demystifying China’s Role in Sri Lanka’s Debt Restructuring,”

The Diplomat, December 20, 2022.

<34> Micheal Pettis, “

Twitter Thread,” Twitter, September 27, 2022.

<35> “

BRI Notebook: Chinese Central Bank Official Calls for Balanced Approach to Debt Crisis,”

Panda Paw Dragon Claw, November 15, 2022.

<36> Ganeshan Wignaraja, “

China’s Dilemmas in Bailing out Debt-Ridden Sri Lanka,”

East-West Center, January 20, 2022.

<37> Moramudali and Panduwawela, “Demystifying China’s Role in Sri Lanka’s Debt Restructuring”

<38> Anushka Wijesinghe, China’s Role in Sri Lanka’s Debt Crisis, interview by Paul Haenle,

China in the World, August 10, 2022.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is a chapter in the journal —

This article is a chapter in the journal —

PREV

PREV