Image Source: Getty

‘Social determinants of health’ are social and economic factors, like food security, financial stability, resources, education, social inclusion, and affordable health services, that influence health outcomes. For poor and disadvantaged populations, the persistent negative patterns in these variables have a disproportionately negative impact on their health outcomes. With the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbating the impact of the various social determinants of health, there is an urgent need to connect people to a social protection network of schemes, programmes, and policies that can safeguard them against food insecurity, poverty, and vulnerability.

The pandemic highlighted the need to improve the awareness and access of target communities to existing social protection schemes.

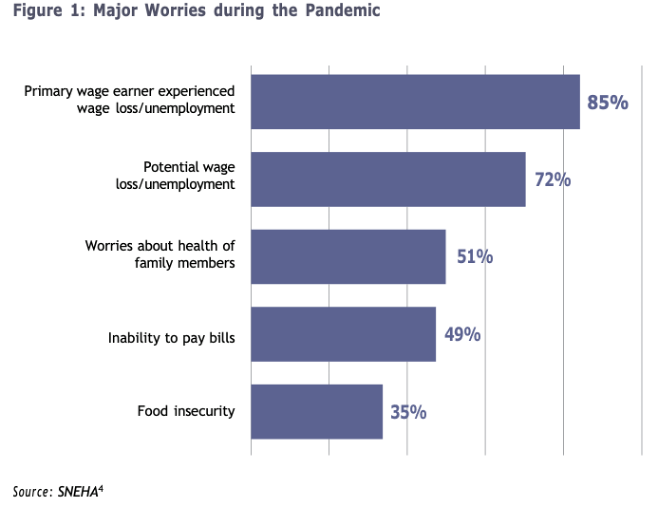

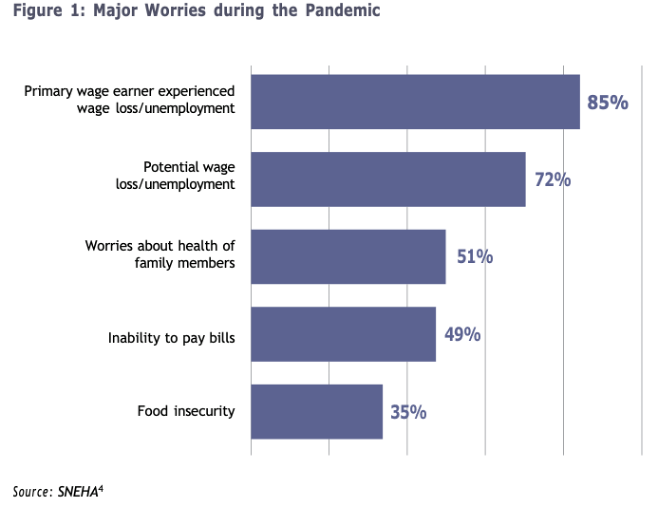

The pandemic highlighted the need to improve the awareness and access of target communities to existing social protection schemes. Towards this objective, in 2021, the Society for Nutrition Education and Health Action (SNEHA),[1] a non-profit organisation working to promote health equity for vulnerable communities in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, initiated a social protection helpdesk.[2] The helpdesk was set up following a needs assessment survey of 1,567 randomly selected community members which found that the pandemic was more of an economic than a health crisis. The extent and nature of the problem, as highlighted in the survey (see Figure 1), facilitated targeted interventions aimed at making the urban poor aware of their entitlements and improve their socio-economic resilience.

Source: SNEHA

Additional insights into the issue were gained through focused group discussions on social protection schemes and collected feedback about the Public Distribution System (PDS)[3]c from 337 ration card holders.

This article is based on findings from these qualitative and quantitative assessments and includes insights from field experiences and a literature review. It highlights disparities in the ground-level implementation of social protection schemes and although confined to the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, the findings can inform future policy interventions for the vulnerable urban poor, especially in slum communities across India.

Limited awareness

The most notable finding was a lack of awareness among intended beneficiaries about the various social protection schemes, their inclusion criteria and procedures, and the entitlements due to them. The pervasive confusion can be attributed to the existence of too many schemes with similar intent that have different eligibility criteria, procedures, and documentation requirements. For instance, both the Janani Suraksha Yojana and the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana aim to promote maternal and child health. The lack of awareness around eligibility criteria and procedures limits the access and uptake of these schemes.

Both the Janani Suraksha Yojana and the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana aim to promote maternal and child health.

Unlike in peri-urban areas and villages, where local administrations act as nodal points to receive scheme-related information and relay it to local communities, municipal ward offices in cities lack connections with vulnerable populations. Field-level government staff also do not have adequate information about the schemes that they are supposed to promote.

Multiple eligibility criteria

Different income-limit criteria for various social protection schemes further complicate the problem. For instance, while Below Poverty Line (BPL) ration card holders with an annual family income of INR 15,000 and less are eligible for benefits under the Janani Suraksha Yojana, those with an income of INR 20,000 or less can access pension under the Sanjay Gandhi Niradhar Anudan Yojana (SGNAY). For those with a disability, the income eligibility criterion for SGNAY is less than INR 50,000. Such mandates create confusion for families that have multiple vulnerabilities, especially since income certificates are usually scheme-specific.

Moreover, the income criteria set by the government for accessing most social protection schemes have remained unchanged for decades. For example, in Maharashtra, after the National Food Security Act (2013) came into force, priority and Antyodaya households, which are entitled to benefits under the Act, were identified based on the socio-economic survey of 1997, disregarding significant changes in the socio-economic status of beneficiaries over the years.

The income criteria set by the government for accessing most social protection schemes have remained unchanged for decades.

Documentation is another challenge, especially for migrants who constitute most informal urban communities. The transient hutments of old migrants make it difficult to safekeep the required documents to prove their eligibility for state schemes such as the SGNAY. The booming land prices make landlords reluctant to provide tenants with the mandatory “no-objection certificate” to obtain a local ration card. For new migrants, food security benefits and other schemes such as the Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Jan Arogya Yojana and the Lek Ladki Yojana, which necessitate the possession of a ration card, remain inaccessible.

Corruption and lack of transparency

“Middlemen” posing as “ration card agents” often charge up to INR 20,000 to supposedly help people in these communities procure new ration cards. Community members highlighted numerous instances of their applications being accepted only if routed through these agents. Such experiences alienate marginalised communities and discourage them from reporting their grievance and seeking redressal.

Further, pilferages and leakages of food grains from PDS have continued despite computerisation. Ration shopkeepers rarely issue receipts from electronic point-of-sale devices, justifying their malpractices as the only way to survive, given low incentives from the government. Ration shopkeepers also often refuse to recognise the interstate portability of ration cards, leaving rightful migrant beneficiaries in the lurch. The inclusion and exclusion errors in recipient lists have also increased over the years. Recipients fear punitive action if they register a complaint about the poor ration quality or that they are receiving less than the quantity entitled to them.

Ration shopkeepers rarely issue receipts from electronic point-of-sale devices, justifying their malpractices as the only way to survive, given low incentives from the government.

Transitioning the social security schemes on digital platforms is also accompanied by its own challenges. For example, the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana portal was non-functional for a long part of 2023, creating a backlog and provoking backlash from communities. Limited and far-flung access points further hamper the uptake of some of the schemes. Janaushadhi Yojana shops that sell generic medicines and provisions like sanitary napkins at reasonable rates are scarce and located far from pockets where such services are most needed.

Streamlining access to social protection schemes

Three years is a short time for vulnerable families to recover after a pandemic. Though questions have been raised about the measurement of the depth of poverty in the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey 2022-23, the indices considered for the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)—the critical socio-economic indicators, including employment, poverty, and access to nutrition (and not just food)—have been reduced to academic concerns. Ground realities call for the following urgent interventions:

- Awareness and capacity building: The implementing government agencies and non-profit organisations must undertake regular awareness-building exercises using media and audio-visual material about various schemes, their benefits, eligibility, and required documents. The Citizen Facilitation Centres (CFCs) in different municipal ward offices can provide information about various social protection schemes as well as their basic documentary requirements. Updated information about all social protection schemes should be made available and accessible over the internet, social media platforms, and SMS channels. Non-profit organisations and civil society partners must play an active role in creating awareness, educating communities to navigate technology, providing guidance to procure documents, linking communities with systems, and building their confidence to demand their rights to social protection. Governments must also ensure periodic capacity building and training of personnel entrusted with implementing the schemes.

- Poverty measurement: The governments must undertake a fresh study to identify BPL families by using revised criteria that align with contemporary contexts, including inflation rates and price indices, rather than relying on sporadic and arbitrary efforts to identify households whose incomes are not commensurate with that specified on their ration cards. Adopting a multidimensional poverty index that does not forgo consumption poverty or the Social Assistance Base concept should be considered to determine eligibility criteria.

- Ease of access: Lack of access leads to a lack of demand, which affects supply. Increased availability and visibility of Janaushadhi shops can be ensured by setting them up at locations that are familiar and accessible to vulnerable communities. Similarly, for other schemes, there is a need to decentralise the application process and create multiple access points.

- Improved digital processes: The digital processes for social protection schemes must be streamlined and contain in-built grievance redressal mechanisms. Mobile app-based information and application processes can be easier than navigating websites.

- PDS surveillance: Vigilance groups such as Ration Dakshata Samiti, aimed at curbing malpractices by ration shop owners, can be reactivated through the participation of citizens and community-based NGOs.

Rama Shyam is the Programme Director of Empowerment, Health and Sexuality of Adolescents at the Society for Nutrition Education and Health Action (SNEHA)

Vinita Ajgaonkar is the Associate Programme Director of Collaborations and Partnerships at the Society for Nutrition Education and Health Action (SNEHA)

[1] The authors of this article are officials of SNEHA: Rama Shyam is a Programme Director and Vinita Ajgaonkar is an Associate Programme Director, leading the domain that works on social protection.

[2] Since 2021, SNEHA’s Social Protection Helpdesk has informed more than 100,000 citizens in vulnerable urban communities on various social protection schemes and benefited 60,000 people.

[3] Operated by the Centre and State/Union Territory governments, PDS ensures the distribution of foodgrains and other essential commodities at affordable prices through Fair Price Shops and is critical to managing India’s food economy.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV