On 16 August, Yuan Wang-5—a Chinese naval vessel—finally docked in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port. Operated by the People’s Liberation Army’s Strategic Support Force, this ‘

research vessel’ can monitor/gather satellite and technical intelligence and also track the trajectories of ballistic missiles. This episode has raised several questions about India’s assistance to crisis-hit Sri Lanka, Colombo’s lack of gratitude for India, and China’s relevance in the region. But India has fewer options except to counter China’s symbolic and strategic messaging, both within and beyond the region.

A Story of Many Contradictions

The episode of docking began amidst political and economic turmoil. The Sri Lankan Foreign Ministry agreed to host the Chinese vessel on

12 July when its President had already fled. Initially, the Sri Lankan Defence Ministry rejected these claims in public. However, in late July, it

was confirmed that the vessel would be docking in Hambantota from 11-17 August for ‘replenishment’ purposes and that there was nothing unusual about it. However, considering the ship’s

potential to track and survey Indian defence and nuclear instalments in its Southern states, New Delhi

expressed its concerns.

The Sri Lankan Foreign Minister met his Indian and Chinese counterparts in Cambodia and received verbal guarantees of further assistance from both. It is quite likely that China demanded guarantees to dock Yuan Wang-5 in these meetings, and India asked to deter the same.

On 4 August, the Sri Lankan Foreign Minister met his

Indian and

Chinese counterparts in Cambodia and received verbal guarantees of further assistance from both. It is quite likely that China demanded guarantees to dock Yuan Wang-5 in these meetings, and India asked to deter the same. Soon after, the Sri Lankan government requested China to defer the vessel docking

until further considerations.

Following this development, China indirectly urged India to

not disturb its normal exchanges and legitimate

maritime activities. The

Chinese embassy also sought an urgent meeting with the Sri Lankan authorities and allegedly held a closed-door meeting with the President. Following these meetings, China received its

new dates of docking from 16-22 August. Sri Lanka defended this move by citing its ‘

international obligations’ and by

ruling out the research activities for the vessel in Sri Lankan waters.

China’s Strategic and Symbolic Messaging

It appears that China’s pressure has played a significant role in docking the ship. This keenness can be explained by three potential reasons.

First, China urges that it will replenish and refuel its vessel in Sri Lanka. But, in that case, Sri Lanka should not be an ideal destination for replenishment, considering its persistent food and fuel shortages and skyrocketing inflation. In other words, replenishment in Sri Lanka does not seem to be the prime motive as it will prove to be a costly affair for Beijing when it can easily find cheaper alternatives.

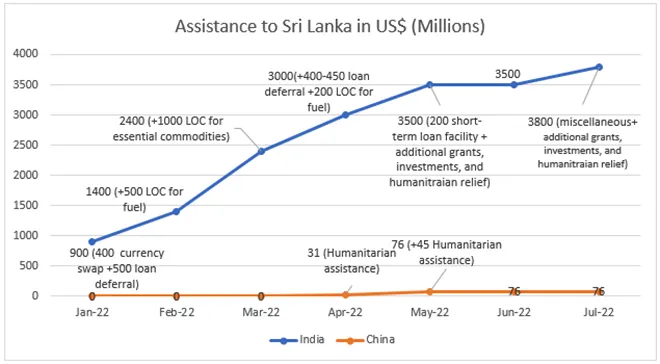

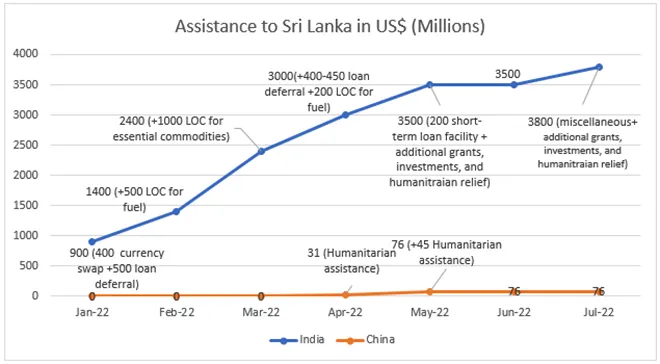

Beijing’s response to the Sri Lankan crisis has been passive (see graph1). It has withheld Colombo’s requests for financial assistance, worth US$ 4 billion, and loan restructuring, hoping to leverage them to further its interests.

Second, there is a growing interest in Beijing to conduct research/surveys and use oceans for its

space-related assignments. The docking could then be a genuine attempt to further China’s research objectives. But there is a contrast here too. While Sri Lanka has imposed restrictions on research, China has maintained that docking is

a part of its marine research activities. Given the context, restrictions from the Sri Lankan government could be to appease India and calm its security anxieties.

While the first two explanations are reasonable to some extent, they still do not justify China’s intense enthusiasm to dock the ship. However, this could be reasoned with an explanation that is subtle, yet more symbolic and strategic.

Traditionally, Beijing’s response to the Sri Lankan crisis has been passive (see graph1). It has withheld Colombo’s requests for financial assistance, worth

US$ 4 billion, and loan restructuring, hoping to leverage them to further its interests. China’s attempts to

expedite the Free Trade Agreement negotiations with Sri Lanka has been one such instance. In this context, the harbouring of the ‘spy ship’ should not be read differently.

China has used Colombo’s compulsion to deliver a strong message to India and the world—regardless of its assistance, Beijing still holds significant leverage in Sri Lanka and could challenge India in its backyard. This is something that China could be more determined to show to the world as its tensions with Taiwan continue to escalate.

China will also likely continue to compel Sri Lanka to toe with its interests in the future with no guarantees of assistance. China realises that President Wickremesinghe will

depend on Rajapaksa’s loyalists for his political survival and also remain sensitive to Chinese interests to improve the economic situation. Further, with Sri Lanka People’s Front parliamentarians

lobbying to dock the ship and

welcoming the vessel, it appears that Beijing is reviving its elite-capture networks in the country.

India: Far from a Diplomatic Failure?

Contradictory to the Chinese approach, New Delhi’s response is based on Sri Lanka’s humanitarian needs and its self-interests. It has assisted Sri Lanka with US$ 3.8 billion, expecting the island nation’s government to respect its interests and sensitivities. India’s assistance has taken in the

form of currency swaps, grants, credit lines, humanitarian supplies, and infrastructure development (see graph 1).

The agreement read that India would manufacture and gift two Dornier aircraft to Sri Lanka, and in the meantime, it would lend an aircraft and a training team to the island nation.

In return, Sri Lanka has

reciprocated by cancelling Chinese projects in the Jaffna peninsula and consenting to India’s investments in the energy sector, Free-Floating Dock Facility, Dornier aircraft, and a Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre (MRCC). One of the sub-units of this MRCC will also be installed in the China-operated Hambantota port.

Graph 1: Assistance to Sri Lanka

The Yuan Wang-5 docking episode might change this understanding between the two countries. It has reinforced fears of the potential misuse of Hambantota port, China’s intentions in the Indian Ocean, and Sri Lanka’s pro-China tilt. But as some

experts suggest, this should not be read as a complete diplomatic failure for the following reasons.

First, unlike China, India has no option but to assist Sri Lanka. New Delhi’s strategic and geographical compulsions barely allow it to sit back and watch Sri Lanka descend into chaos—a privilege that Beijing enjoys. Essentially, India’s approach to Sri Lanka has been

people-centric. It has

advocated to promote democracy, stability, and recovery, and has continued with the assistance regardless of the political and economic changes.

Second, New Delhi’s earlier assistance has already facilitated it to make some notable gains in Sri Lanka. One such instance is India’s leveraging of its agreement on Dornier aircraft. The

agreement read that India would manufacture and gift two Dornier aircraft to Sri Lanka, and in the meantime, it would lend an aircraft and a training team to the island nation. This was leveraged on

15 August—a day before the Chinese vessel docked. India’s Chief of Navy visited Sri Lanka to donate a Dornier aircraft that will now be supervised by an Indian team. This displays that India’s engagement has already created a ground to further its interests and counter Chinese offensive ambitions.

Any misadventure of denying or differing assistance to Sri Lanka also risks attracting more Chinese influence and undoing the positive gains of the last two years.

Third, the writing on the wall has always been clear. India’s assistance was not aimed to root out Chinese influence; it was out of compulsion and to reverse its lost influence. It is no secret that China’s investments and loans still largely outweigh New Delhi’s financial assistance. In fact, even India knows that the

IMF bailout solution it supports would require Sri Lanka to talk to China and restructure its loans.

In the end, India should continue with its diplomatic engagement and assistance. India’s response to the crisis is not only strategic and status-oriented, but also symbolic since its Indo-Pacific partners expect it to play a significant role in the region. Any misadventure of denying or differing assistance to Sri Lanka also risks attracting more Chinese influence and undoing the positive gains of the last two years. Something that could change is perhaps New Delhi’s message—if the Indian Ocean can no longer be India’s Ocean, then the China Sea will also no longer be China’s sea.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

On 16 August, Yuan Wang-5—a Chinese naval vessel—finally docked in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port. Operated by the People’s Liberation Army’s Strategic Support Force, this ‘

On 16 August, Yuan Wang-5—a Chinese naval vessel—finally docked in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port. Operated by the People’s Liberation Army’s Strategic Support Force, this ‘

PREV

PREV