The 2020 BRICS Summit was held virtually amidst the COVID-19 pandemic under the chairmanship of Russia, which adopted the motto for the year as ‘BRICS Partnership for Global Stability, Shared Security and Innovative Growth.’ At the end of the 2019 summit in Brazil, President Vladimir Putin had declared that special attention would be paid to “expanding foreign policy coordination between our states on key international platforms, primarily at the UN.” Another goal was to update the strategy for economic partnership signed in 2015 and formulate a strategy that will set the agenda for BRICS cooperation till 2025.

The achievement of these goals in 2020 took place in the backdrop of the pandemic, which has hastened the upending of the post-Cold War order.

These goals also form part of broader Russian strategic objectives towards BRICS, which include reforming the prevailing institutions of economic governance, pursuing a multi-vector policy and expanding foreign policy cooperation with BRICS members, and to use these measures to strengthen the international position of the country. The achievement of these goals in 2020 took place in the backdrop of the pandemic, which has hastened the upending of the post-Cold War order. The impact of this development on BRICS as an organisation and on its stated aims can hardly be underestimated.

Key documents

In a step forward, the Strategy for BRICS Economic Partnership 2025 was signed, having been up for review at the end of a five-year period. Focusing on three priority areas — trade, investment and finance; digital economy; and sustainable development — it seeks to chart out the future course of action for BRICS economic cooperation. It is clear why these three areas were chosen, having also formed an integral part of the previous strategy developed in 2015, reflecting the future economic priorities and focus areas of member-states.

Focusing on three priority areas — trade, investment and finance; digital economy; and sustainable development — it seeks to chart out the future course of action for BRICS economic cooperation.

The adoption of the strategy does indicate a commitment to carry forward the existing cooperation between members on areas like promoting cooperation among businesses of BRICS countries; reforming of WTO, IMF and World Bank; advancing the Contingency Reserve Arrangement (CRA); and strengthening the New Development Bank (NDB). Other areas include innovation and technology, challenges of digitalisation and the Fourth Industrial Revolution, sustainable development, climate change, energy, infrastructure development and food security. The coordination of Russia with Brazil, India and China over tests and production of COVID-19 vaccines has been presented as a win for intra-BRICS coordination. Also, the NDB setting aside $10 billion to help members deal with the cost of the coronavirus crisis has been an important development for the bank at a time when discussions about the expansion of its membership are gathering steam.

While these are all areas of concern for BRICS, where cooperation is seen to be beneficial and, indeed, the economic and financial sector is the core area where the organisation has had the most success through institutionalisation of mechanisms like NDB and CRA, the short to medium term is hardly expected to be a smooth ride. For instance, while China has called upon BRICS states to build cooperation on “digital transformation, especially in 5G, AI, the digital economy and others,” India has since the recent border clashes set out to prevent Chinese telecoms from participating in its 5G trials. In the aftermath of India-China border tensions earlier in 2020, India has ruled that for any FDI originating from a country that shares its border, government approval will be mandatory citing national security concerns. This means that all investments from China will have to go through this route, even though the BRICS strategy calls for strengthening investment cooperation. By July, this had already led to about 200 Chinese proposals being left pending before the Indian home ministry.

All investments from China will have to go through this route, even though the BRICS strategy calls for strengthening investment cooperation.

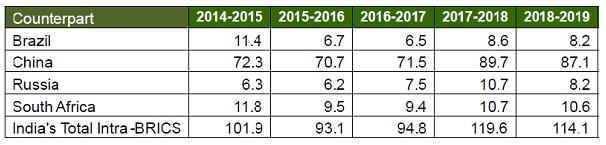

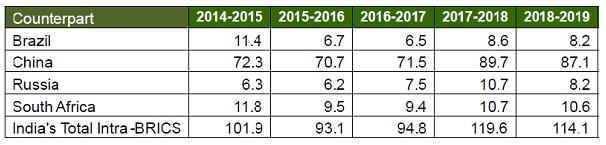

In terms of enhancing trade in an intra-BRICS setting, Russia has had limited success. In 2019, its overall trade with BRICS touched $125 billion, of which $110 billion was with China. Its trade with India, though registered a growth, still remains at the $10-11 billion mark. India’s total intra-BRICS trade, which stood at $114.1 billion in 2018-19 also saw China contribute the vast majority of it at $87.1 billion.

India’s trade with BRICS ($ billion)

In 2014, Russia’s trade with Brazil and South Africa stood at $6.25 billion and $975 million respectively. By 2019, the former had registered a decline to reach $4.61 billion while the latter had improved very marginally at $1.11 billion. UN Comtrade data suggests that Brazil-South Africa bilateral trade stood at $2.06 billion in 2010 while in 2019 it had declined to $1.88 billion. While these challenges do not preclude the viability of the economic partnership strategy, the challenges of an intensifying US-China bipolarity on economic decision-making will have to be factored in, especially given that two key member states are also experiencing deterioration in their bilateral ties, limiting the avenues for cooperation for the organisation as a whole.

The challenges of an intensifying US-China bipolarity on economic decision-making will have to be factored in.

The members also signed the BRICS counter-terrorism strategy with the objective of contributing to the global efforts to combat terrorism while also strengthening intra-BRICS ties in the area. This includes improving intelligence sharing on terrorist organisations listed by the UN Security Council, cracking down on their sources of finance and preventing the spread of terrorism. India has noted that as it takes up the presidency of BRICS for 2021, it will “pursue this task further.” The Moscow Declaration, in general, did not contain any major new announcements and the themes of last year were repeated almost throughout the document under the sub-headings of Policy and Security; Economy and Finances, Intergovernmental Cooperation; and Cultural and People-to-People Exchanges.

Russia’s announcement of wanting to expand foreign policy coordination within BRICS at the start of its presidency has been one of the most elusive aims in the past year. Despite the long list of ongoing international events that find mention in the declaration, it has largely been simply an expression of ‘opinion.’ This has led scholars to note that ‘expressing a shared stance’ does not translate to setting rules as a grouping.

The international situation

The emerging global trends have also made Russia’s goals with respect to BRICS more complicated, given that the global system in which the organisation was established has been altered radically in the present times. While it is true that BRICS nations list one of their aims as establishment of a multipolar world order, they are hardly on the same page regarding its realisation, especially as Chinese power has outstripped that of any other member-state. A more aggressive China in recent years has put it in a contentious relationship with India, in particular after the border clashes earlier this year amidst an ongoing pandemic.

While it is true that BRICS nations list one of their aims as establishment of a multipolar world order, they are hardly on the same page regarding its realisation.

While till now China has not asserted a dominant position within BRICS and both India and China have cooperated within its framework while managing their bilateral differences outside of multilateral frameworks, a continuation of a similar policy remains unclear at the moment. If the US-China bipolarity intensifies, as is being predicted, both India’s and Russia’s relations with these two major powers will reflect in their foreign policy behaviour. The actions of the three leading powers of BRICS will determine the internal dynamics and the resultant impact on the future of the organisation.

An adverse scenario has the potential to limit the role BRICS can play in global governance or serve as a non-western grouping building a multipolar world, thus ‘negatively impacting the viability’ of the organisation. Till now, BRICS has managed to deal with these challenges, but the changing world order will make the task of balancing more difficult than ever.

Overall assessment

Largely, the BRICS summit this year was built on the economic engagement of the previous years. In this context, it is clear that member states have found common interests on which they are willing to cooperate through the format of established mechanisms and institutions. Also, at a time when the global system is in flux, BRICS members have found it relevant to continue to explore areas of cooperation, especially as the new world order is yet to be formed.

It remains to be seen if the existing institutionalisation would be enough to continue to drive the organisation forward and how will it evolve in a changing world order.

Yet, it is safe to say that the BRICS 2020 summit did nothing to quell questions about its future course of action in light of the challenges mentioned above. It remains to be seen if the existing institutionalisation would be enough to continue to drive the organisation forward and how will it evolve in a changing world order. This will also determine whether the organisation will prove to be successful in fulfilling Russian strategic objectives in the coming years, in addition to helping it deal with the impact of economic sanctions and breakdown of relations with the West in the aftermath of the 2014 Ukrainian crisis.

India has already seen the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global system leading to a rethink of several of its foreign policy measures. As it takes over the presidency of BRICS for 2021, India’s conduct as the chair will be an indication of how New Delhi sees its own position within BRICS going forward. This will be an interesting development to watch in light of its complicated relations with China, a growing closeness with the US as well as the implications of the growing Russia-China rapprochement.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV