-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

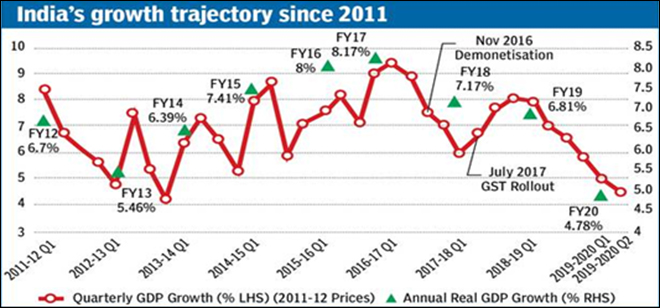

The Indian economy had already been showing signs of distress much before the arrival of the pandemic. Any attempts of reviving the economy have only become more difficult as the effects of a lockdown have intensified the downward pressures on the economy. In simplistic terms, the national income of a country is determined by private and government consumption expenditure, investments and net exports. With countries shutting down foreign trade in almost all goods and services, there is little hope for export-driven growth now. According to estimates, global trade is going to take some time before it returns to pre-pandemic levels, not to mention the inability to return to pre-2008 levels. Therefore, economic policy making must focus exclusively on the domestic front and harness the country's immense labour potential to make significant progress along developmental indicators.

Figure 1. India's Growth Trajectory

Source: "COVID-19: Another blow to India's economy", The Hindu Business Line, March 30, 2020.

Source: "COVID-19: Another blow to India's economy", The Hindu Business Line, March 30, 2020.

Indicators of economic activity such as automobile sales and production have been reflecting a very pessimistic outlook, with major producers in the automobile sector downsizing their existing capacities or reporting a steep decline in their growth figures. Additionally, in the last two months the manufacturing purchasing manager's index (PMI) has also experienced its sharpest decline, and was among the lowest globally. Surprisingly, despite several service sector activities continuing amidst the nationwide lockdown, the decline in the services PMI was even more extreme (falling to 5.4 in April from 49.3 in March) caused by a negative expectation of future business prospects, and thus dampening the likelihood of a services-led revival of the Indian economy. Furthermore, the growth rates related to gross fixed capital formation dipped to -0.61% in the year 2019-20, implying negative investments.

Akin to the great depression of the 1930s, the problem today is also that of effective demand. As such, stimulus packages must focus on reviving demand. Although the government has announced an additional package aimed at infusing liquidity into the economy, its efficacy is dependent on the stimulation of demand. With the aspirational class and the lower segments of society exhibiting higher propensities to consume, it is necessary to boost their income and/or income earning opportunities. However, as a result of non-inclusive policies, income inequality in India has seen a rising trend. Growing inequality further aggravates the problem of effective demand by leaving lesser income in the hands of those willing to spend more.

In this vein, it is important to identify the right policy mix of both fiscal and monetary measures that will directly boost employment and effective demand in the economy, which will then automatically feed into private investments by boosting business sentiments. This can be achieved through employment generation facilitated by direct fiscal expansion or redistributive taxation resulting in income redistribution and higher consumption demand. The government may find it more favourable to work towards fiscal expansion led by expenditure in infrastructure development- both social and physical.

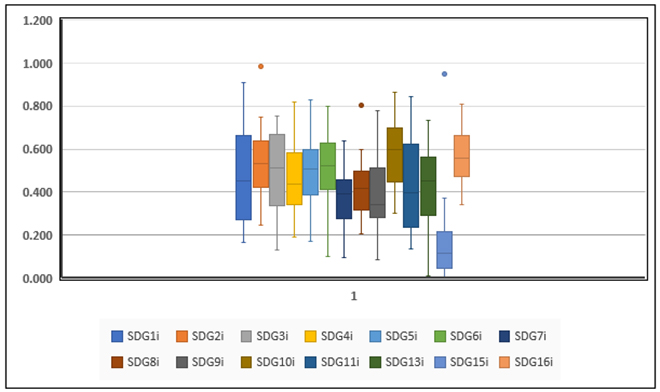

Identifying gaps in social development across the country can provide a yardstick for developmental policy making. The objective of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is likely to get delayed due to impacts of a nationwide lockdown. But policy makers can capitalise on the current situation by targeting fiscal expansion in sectors that improve India’s status across developmental indicators. Not only will this provide a significant boost to the development trajectory, but also ensure progress along the SDGs. In the following figure, the distribution of state-wise performance across SDGs has been depicted. Each box represents the spread of the scores of the individual states across various SDGs. The line inside the box represents the median score and can depict the average performance in terms of these respective goals. Based on the median score, SDGs 1, 4, 7, 8 and 9 are some of the goals that have shown laggard performance.These goals across parameters such as poverty alleviation, quality education, clean energy, decent work and infrastructure; and capture elements of social, physical and human capital. They have strong forward and backward linkages and investments in one can have positive spill-overs on the others.

Figure 2. Distribution of index scores across various SDGs

Source: Author’s calculations using data from Ghosh, Bhowmick and Saha (2019)

Source: Author’s calculations using data from Ghosh, Bhowmick and Saha (2019)

Improvements in SDG 1, i.e. ‘No Poverty’, can be brought about through expansion of employment guarantee schemes such as MGNREGA in rural areas and expanding it to include informal workers in urban areas as well. Protection of urban informal workers is extremely important because most of them are migrant workers and they can fall prey to uncertainties that leave them in abject poverty. The aftermath of the lockdown has provided ample evidence of this. These expenditures will not only ensure social security, but also help in reducing income inequality. Furthermore, investments in clean and renewable energy (SDG 7), through government schemes can provide jobs, and energy security. Funds can be channelled through the Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency (IREDA) to boost investment in the sector. It has high employment potential across skill levels, and can strengthen progress towards achieving SDG 8 as well.

Achievement of 'education for all' as enshrined in the goals of SDG 4 provides another area of opportunity to expand government expenditure. Although estimates suggest that government expenditure in education has increased over the five years, it is still below 6 percent of GDP- a figure that the NITI Aayog suggests is necessary to achieve quality education, thereby suggesting the potential of increasing government expenditure in this sector. With adequate focus on the primary and secondary levels of schooling, additional expenditure must be focussed on vocational training, higher education and research and development. They have a strong favourable influence on human capital development.

SDG 9 focuses on Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, and developing basic infrastructure has a huge potential of creating jobs and generating income. In the current context, with a lack of convergence across states in terms of infrastructure development, fiscal measures must promote investment in states that have remained relatively backward. These states are also the native states of the migrant labours across the country. With uncertainty over inter-state transport, and the plight of the migrant labourers, employment opportunities closer to home would be widely acknowledged. Through the respective state governments, infrastructure development, in the form of roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, drainage systems etc., can be undertaken in the relatively backward states. This will greatly help in increasing income and aggregate demand in the economy, and also promote balanced regional development by reducing the gaps between states across the country.

Generating employment opportunities through large scale investments in some of the aforementioned sectors will have a multiplier effect on the economy. It is not just in the context of post-pandemic economics, but in the overall developmental planning of the country, that these expenditures are necessary as they entail certain essential public goods.

It may be argued that additional government expenditure might not be compatible with the fiscal discipline of the economy by generating larger fiscal deficits. But, one must understand that a country cannot afford to focus excessively on fiscal discipline especially at a time when unemployment is at a high and economy is in a turmoil. Undoubtedly, there are macroeconomic impacts of a high fiscal deficit, but they can be circumvented if government expenditure is incurred in developmental activities that underpin future demand. Therefore, one can most definitely argue that increased government expenditure need not necessarily lead to an increase in fiscal deficit which results in inflationary pressures. In fact, pegging the fiscal deficit to the GDP can be counter-cyclical with lower expenditure resulting in lower income and lower tax revenue entailing further decline in government expenditure to maintain the FRBM norms. This is a viable option when the economy is functioning well, and unemployment is at the natural rate, with very little need for government expenditure. But, in the current context, where the economy was already slipping downhill (figure 1), curtailing government expenditure may not be desirable.

Also, once the economy is set on its path to recovery, greater demand will also encourage private investors, ultimately leading to what may be termed as a “crowding-in” effect of government expenditure. It is only then that the monetary policies pursued by the RBI may complement the fiscal policy. Additionally, the banking and finance institutions have been wary of lending, consequently lower repo rates have not translated into lower PLRs. Furthermore, this unwillingness is ratified by the quantum of cheap funds being made available being more or less the same as the increase in the amount being deposited back in the RBI. But the current credit support scheme might address this gap to some extent. Nonetheless, even if the PLRs go down, there is no actual demand for credit in the market owing to the uncertainties.Thus, even for a monetary policy to work its magic in reviving the economy, a large fiscal stimulus, aimed at generating employment and demand, is necessary.

Roshan is a Research Assistant, and Debosmita is a Research Intern at ORF, Kolkata.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Debosmita Sarkar was an Associate Fellow with the SDGs and Inclusive Growth programme at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation, India. Her ...

Read More +

Roshan Saha was a Junior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation Kolkata under the Economy and Growth programme. His primary interest is in international and development ...

Read More +