-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The US-Taliban agreement on February 29, 2020, after 18 months of negotiations, and more importantly, 18 dreadful, even desultory, years of incessant fighting and killing, offers an opportunity to turn things around in Afghanistan. But, there is widespread concern about what the future holds for the war-weary country. Not only does the ‘peace deal’ between the US and Taliban leave the question of Afghanistan’s political future open, it is predicated on a rather heroic assumption that the Taliban have transformed and evolved, and they are no longer the fanatical, barbaric and uncompromising force they were in the 1990s. There is, however, no evidence to justify this assumption. Quite to the contrary, the Taliban have dropped enough hints that when it comes to the future political dispensation, “in the presence of a legal emir

While the US urge to withdraw from Afghanistan is entirely understandable – politically it enjoys no support at home, economically it is a drain, strategically it is diverting attention from other bigger challenges, and militarily it is a quagmire – what doesn’t make sense is the Americans frittering away all the gains made in Afghanistan in the rush for the exit. It makes even lesser sense for the US to throw its Afghan allies to the wolves by entering into a bad deal with the Taliban when, with an exit with no deal but with a minimum level of economic and military support to the current dispensation in Kabul, the Americans can change the chessboard in Afghanistan. In other words, the US can gain a lot more for a lot less than lose a lot more to save a lot less. What the US needs to do is upend the calculations of their enemies by using the leverages they still enjoy in Afghanistan in spite of all the political mess and the military morass.

The leverages are: 1) no one really wants to see the Taliban ruling the roost in Afghanistan – not the Americans, not the Russians, not the Iranians, not the Chinese. And yet, this is exactly what will happen if the things continue on the current trajectory; 2) Not everyone wants to see the Americans continue their presence in Afghanistan – not the Americans, not the Russians, not the Iranians, not the Taliban, and perhaps not even the Chinese. It is this negative leverage that can be invoked by the US to threaten the other players with what can be called the Samson Option; 3) No one is sure who will financially underwrite whichever dispensation replaces the current regime – it is unlikely that the Russians, Chinese, Iranians, Saudis, Emiratis (Pakistan doesn’t count because it cannot manage its own finances) would don the mantle. The Afghan state is quite simply unviable and without some kind of financial support, the entire edifice of government will collapse. Although, the US has promised to stay engaged, there is deep scepticism about the US bankrolling Afghanistan once it exits. US allies too are unlikely to pump money in Afghanistan once the US funding is squeezed; 4) No one, especially the Pakistanis, wants to see an abrupt withdrawal. What Pakistan wants is to comprehensively influence and dictate the political dynamics of the Afghan state, while the US, the NATO or any other entity, foots the bill. Everyone therefore, including the Pakistanis, wants a smooth transition of power to the new dispensation. A hasty withdrawal could lead to a civil war like situation in Afghanistan, something that will lead to prolonged regional instability. The ultimate beneficiaries of such a situation are going to be the Islamists – Taliban, Al Qaeda, ISKP and the rest of the menagerie of jihadist terror groups operating from Afghanistan. Taken together, these leverages contain the seeds of a new policy that doesn’t involve a Faustian bargain with the Taliban and the consequences that flow from such a bargain.

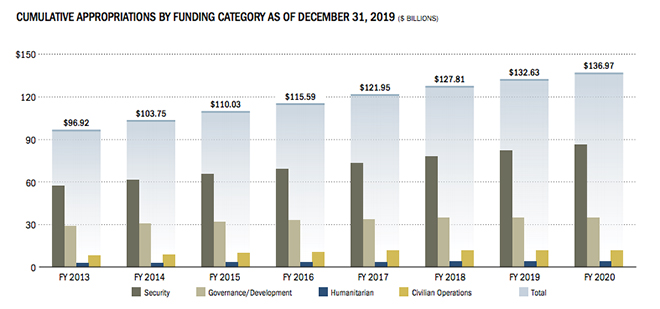

According to the US Department of Defence ‘Cost of War’ report dated September 30, 2019, the US has spent around $776 billion until now, of which 16% was directed towards reconstruction efforts. The cumulative aid provided solely for use by Afghan authorities for security, governance and development, humanitarian assistance, and oversight and operations, is $137 billion. (See figure below)

Given that around 75% of the Afghan government’s public expenditure is sourced from donor countries in the form of international aid, a possible decision by the US, the biggest donor, to rescind a significant amount of monetary assistance in the near future, would surely cause irreversible damage to the war-torn country. Owing to heavy dependence on international aid at the moment, a sharp decline in the ready availability of military and developmental grants would render the Afghan government helpless and unable to meet even the most pressings demands of the population. No other country from the existing list of donors would be in a position to fill in for the US, given the sheer size of the American aid package.

For much of its history, Afghanistan has been a war economy in which regimes fall when they were no longer able to sustain themselves economically and pay the soldiery – precisely what happened to the PDPA regime of Dr. Najibullah after the drying up of military and economic assistance, following the collapse of the Soviet Union. This inevitably led to desertions and switching sides, which in turn paved the way for a new dispensation. This cycle can be broken, provided the US and its allies forsake the pennywise pound foolish policies that seem to be guiding their choices in Afghanistan.

The withdrawal of all foreign troops from Afghanistan would take away the biggest reason touted by the Taliban to justify their insurgency. The withdrawal will also satisfy domestic constituencies in the US and its allied countries, which suffer from a fatigue with a war that seems to be going nowhere. Regional powers, which aren’t exactly keen on a Taliban-led regime but are more spooked by US presence in Afghanistan, will turn their focus on preventing a Taliban takeover once the US exits. For its part, the US will no longer need to spend over $100 billion per year in its war effort in Afghanistan. For a fraction of this amount, and at virtually no cost in American lives the US can ensure that it doesn’t create a situation in which the Taliban capture power in Afghanistan.

Although the momentum is currently with the Taliban, and as is normal in such circumstances, many of the people who aren’t exactly enamoured of the Taliban, will shift their support to them as part of a survival strategy. But there are also those who face an existential danger if the Taliban come to power. These include powerful warlords, tribal chiefs, ethnic groups, political leaders, soldiers and officials. These are people who face the stark choice of either fighting or dying, and this being Afghanistan, many of them would rather die fighting than be slaughtered by the Taliban. What they need is support – monetary and military. Not boots on the ground, but money to run the government, to pay the soldiery, and weapons to fight the Taliban. The budget of the Afghan state is around $6-8 billion. While this number seems pretty substantial, for the US and its European/NATO allies, which together generate a GDP of over $ 40 trillion, to spend this money to fund forces which will fight the Taliban is really a pittance, even more so considering the money which they are spending on keep their forces in Afghanistan at present.

Instead of undermining the Afghan government, and empowering the Taliban (which is what the US-Taliban accord has actually done), the US should beef up the Afghan government and anti-Taliban forces by giving them the wherewithal needed to fight the Taliban. Let them decide how they want to fight this fight. Don’t impose unrealistic conditions on them on fighting this war in an antiseptic way when their enemy doesn’t follow any rules of civilised conduct.

The US administration must realise that just because the military solution proved grossly inadequate, does not mean other tools of reconstruction should not be employed to retain the gains of the past. In the absence of boots on the ground, it must continue to not only provide the Afghan government with the military and financial aid it requires to combat the Taliban and affiliated organisations, but also use trade pacts and development aid to keep the stakeholders hooked onto any power-sharing arrangement that takes shape in future. In order to achieve this, the US needs to double down on using economic leverages against countries like Pakistan, which have sabotaged the war effort since after 9/11. In the past, the US has been rather diffident in using economic sanctions has a lever against Pakistan, but in recent months, we have seen that the Americans have used military and economic assistance, FATF, and the IMF package to force a degree of compellence on Pakistan. This strategy needs to be taken to the next level, to ensure a favourable outcome in Afghanistan, post withdrawal.

President Trump must therefore curate an exit strategy that calibrates to contemporary economic realities, to avoid delivering a blow to Afghan institutions and socio-economic practices in the presence of a resurgent Taliban. Doing so would be essential in order to sustain and consolidate conditions of peace in Afghanistan.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sushant Sareen is Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation. His published works include: Balochistan: Forgotten War, Forsaken People (Monograph, 2017) Corridor Calculus: China-Pakistan Economic Corridor & China’s comprador ...

Read More +

Shubhangi Pandey was a Junior Fellow with the Strategic Studies Programme at Observer Research Foundation. Her research focuses on Afghanistan particularly exploring internal political dynamics ...

Read More +