This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed existing vulnerabilities associated with international trade, especially for developing countries that are heavily linked into existing global value chains (GVCs). Disruption in the existing manufacturing GVCs due to the pandemic, on the back of disruptions caused by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, has led to a drastic fall in the exports of many developing countries and a decline in the import content of their exports. This has necessitated a rethinking of trade policies in developing countries.

With growing digitalisation and amid the ongoing pandemic, India needs to reorient its trade policy with emphasis on developing its own GVCs and upgrading existing ones to accelerate its export diversification. This has become important given India’s falling export competitiveness, especially in labour-intensive sectors like textiles and clothing, gems and jewellery, and leather and leather products. India can achieve a sustainable V-shaped recovery — a strong recovery after a harsh economic decline — in its manufacturing exports by adopting certain specific strategies, such as strengthening the ‘right kind’ of GVC linkages and leveraging digital technologies.

India’s export competitiveness

Although India’s overall exports have been rising, crossing over US$ 300 billion in 2018, there has been a steady and sharp decline in merchandise export growth after 2011<1>. While this has coincided with the global slowdown, importantly, India’s comparative advantage in its traditional exports has been shrinking. Between 2011 and 2017, India experienced a fall in its revealed comparative advantage in over 75 products at the three-digit product level, including in traditional export products — precious stones, spices, jewellery, cotton, tea, fabrics, clothing articles and leather<2>.

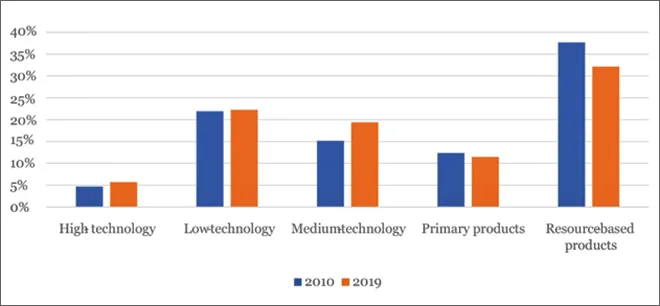

Resource-based exports and low-tech exports continue to dominate India’s export basket.

However, some export diversification has taken place, both in terms of products and markets. In 2018-19, the top 10 exported products accounted for 60.6 percent of total exports, a decline from the 62.7 percent in 2010-11, indicating that India’s dependency on its traditional exports have fallen by roughly 2 percent<3>. Products that have seen an increase in India’s export basket include nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery and mechanical appliances; vehicles other than railway or tramway rolling stock or related parts and accessories; organic chemicals; pharmaceutical products; and iron and steel. Diversification has also occurred in terms of destination markets, with the total share of India’s leading export markets declining from 50 percent in 2010-11 to 45.5 percent in 2018-19<4>.

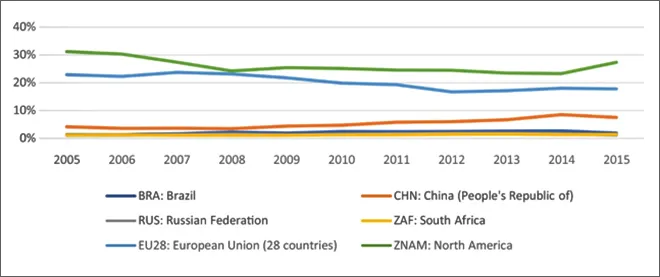

Overall, the share of primary products and resource-based products in India’s total exports declined in 2019 as compared to 2010, with a significant rise in the share of medium-tech exports, from 15 percent to 19 in the period (see Figure 1). However, resource-based exports and low-tech exports continue to dominate India’s export basket; in 2019, 32 percent of India’s exports were resource-based, followed by 22 percent of low-tech exports. High-tech exports accounted for less than 6 percent of total exports.

Figure 1: India’s goods export structure, by type of good (percent)

Source: Author, constructed from the World Integrated Trade Solutions database<5>

Source: Author, constructed from the World Integrated Trade Solutions database<5>

Note: Lall’s classification categories (2000) are followed<6>. Primary products include fresh fruit, meat, rice, cocoa and tea. Resource-based products entail simple and labour-intensive processing, such as prepared meats/fruits, beverages and wood products. Low technology products include textile fabrics, clothing, headgear, footwear and leather manufactures. Medium technology products include vehicles/motorcycles and parts, synthetic fibres, chemicals and paints. High technology products have “advanced and fast-changing technologies, with high R&D investments and prime emphasis on product design,” such as office/ data processing/telecommunications equipment, TVs and pharmaceuticals.

COVID-19: Accelerating the need for export diversification

As the pandemic struck in early 2020, the need for export diversification in terms of products and markets emerged as a necessary strategy for building economic resilience against such shocks. India’s GDP and exports were significantly hit by supply and demand disruptions. In the first quarter of the financial year, India registered a negative growth rate of 23.9<7>. In November 2020, India’s exports declined by 9 percent year-on-year and imports by 13.3 percent<8>. In response to the pandemic, manufacturing firms began re-purposing production towards the manufacturing of personal protection equipment (PPE), medicines and other medicinal equipment. For instance, Mahindra and Mahindra and Maruti Suzuki, India’s major automobile producers, geared production towards the manufacturing of ventilators<9>. Similarly, textile and garments manufacturing firms moved towards the production of masks and PPE<10>. Meanwhile, the electronics and pharmaceutical sectors were critical during the pandemic for boosting exports.

A PLI scheme has been introduced to attract large investments to promote domestic manufacturing of critical active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), in addition to a scheme for bulk drug parks, with the aim to reduce the manufacturing costs of bulk drugs in the country.

Government efforts to curtail the spread of the virus in India also accelerated digitalisation across the country. Data consumption peaked at about 70 percent of pre-lockdown levels<11>, with growth in education technology, work-from-home business models, mobile commerce, e-commerce and digital payments. To meet the subsequent increase in demand in the electronics sector, India announced the production linked incentive (PLI) scheme for large-scale electronics manufacturing, schemes for electronics manufacturing clusters (EMC) 2.0 and the promotion of manufacturing of electronics components and semiconductors<12>. The pharmaceutical industry has also emerged as a key sector for India’s export development. A PLI scheme has been introduced to attract large investments to promote domestic manufacturing of critical active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), in addition to a scheme for bulk drug parks, with the aim to reduce the manufacturing costs of bulk drugs in the country<13>.

Climbing-up the GVC export ladder

The positive effects of learning by exporting and learning by importing are well-documented. Exporting enables firms to gain access to foreign markets and international consumers and induces competition and innovation, which improves the exports performance of supplier firms. Similarly, access to import markers allows supplier firms to access cheaper and better-quality intermediate inputs and to learn from the technology embedded in them. The GVC trade-related literature looks at two-way trading. Some studies find that GVC firms (two-way traders) fare better than one-way traders since they can learn from both importing and exporting, and benefit from the rising cost complementarities of simultaneously engaging with both activities<14>. The benefits of GVC participation towards increased efficiency gains and export diversification are well documented<15>, and evidence suggests that GVC firms are more likely to introduce new products<16>. However, linking into GVCs is not enough; it is also important to increase the domestic value-added content in exports<17>.

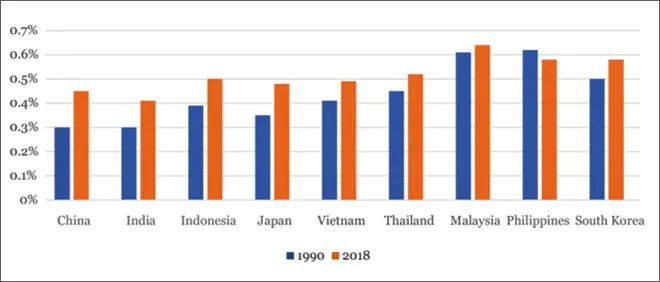

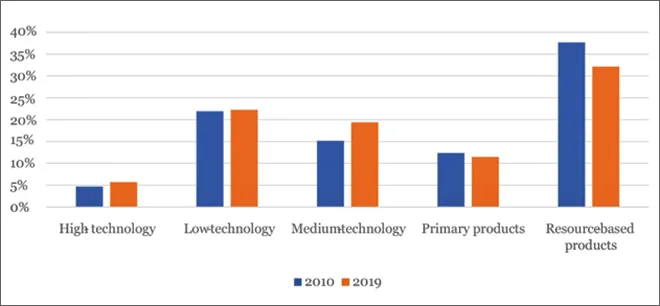

India has been a unique case when it comes to participation in GVCs. Despite being in proximity to ‘Factory Asia,’ it is less linked in GVCs than its comparators (see Figure 2) due to a range of factors, including stagnant growth in the manufacturing sector, lower ability to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) to the sector, an unfavourable business environment and financial constraints faced by manufacturing firms<18>. A key strategy for export diversification is to link into GVCs. Although caution is warranted, linking into GVCs is not the end-goal, nor are the benefits from linking automatic or homogenous. The aim should be to diversify into more sophisticated products that capture higher economic rents and value-added. Rising product sophistication shifts out the technological frontier of a country and improves its growth performance, enabling the country to climb up the export value chain<19>.

Although caution is warranted, linking into GVCs is not the end-goal, nor are the benefits from linking automatic or homogenous.

For Indian manufacturing firms, the average product sophistication in GVC firms is roughly 2 percent higher than that in non-GVC firms<20>. Ultimately, opportunities for Indian firms to undertake export diversification and sophistication are crucially linked to the governance structures of the GVC they are operating in<21>. For instance, vertically integrated (FDI-driven) chains offer higher opportunities for supplier firms to upgrade products<22>. Knowledge spill-overs from downstream multinational enterprises (MNEs) have been found to positively impact Indian firms’ product sophistication<23>.

India has great potential for attracting investment from MNEs, particularly as several MNEs look to diversify and shift their production facilities away from China in the post-pandemic era. But if the aim is export diversification, a more nuanced understanding of FDI is needed. FDI has a positive impact on the total factor productivity of Indian manufacturing firms, but the impact is higher for FDI from developed economies, such as the US and European countries, while for productivity spill-overs from FDI in upstream sectors, the impact is higher in the case of Asian countries compared to US and Europe<24>. Efficiency gains from productivity spill-overs can be reinvested into export diversification.

If the aim is export diversification, a more nuanced understanding of FDI is needed.

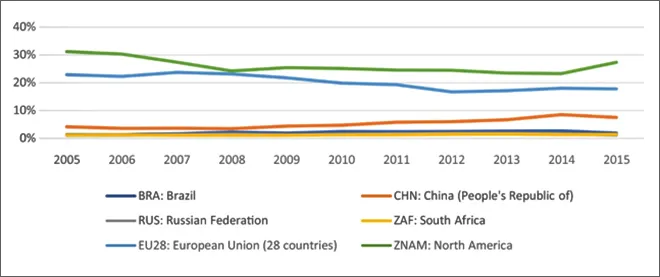

Figure 2: GVC participation rate of India and comparators

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development- World Trade Organisation<25>

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development- World Trade Organisation<25>

Note: GVC participation rate is measured as the sum of imported intermediates used in the production of a country's exports and local inputs used in the production of other countries' exports, expressed as a percent of gross exports. A higher value signals deeper integration into GVCs.

Initiating India’s global value chains

The maximum gains in GVCs are derived by the lead firms, which initiate and control the value chains and are predominantly based in the Global North. But there appears to be a growth in South-South trade — with emergence of lead firms in the Global South that supply to end markets within the Global South<26>. For example, South African supermarkets have expanded their retail operations across different parts of Sub-Saharan Africa<27>, while Southern Africa’s apparel sector has witnessed an expansion of regional value chains<28>.

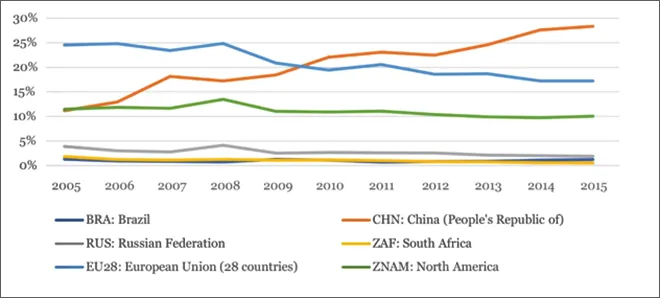

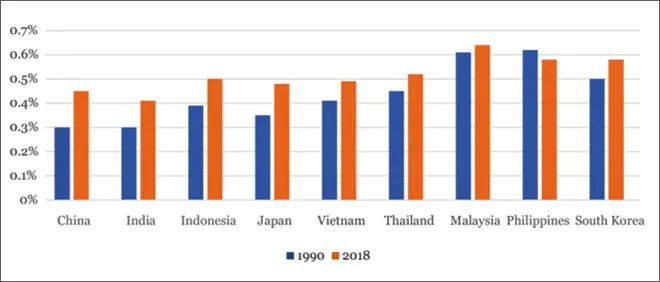

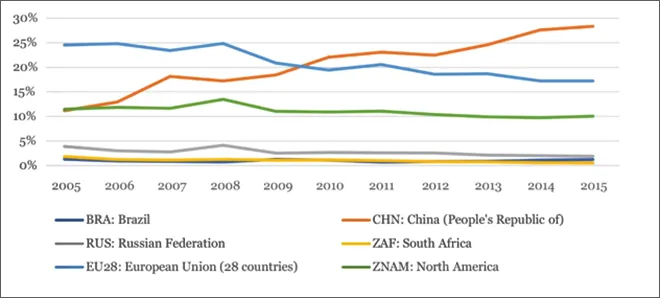

India falls behind other developing countries in terms of its participation rate in GVCs and has very few GVCs of its own with Indian firms as the lead potentially due to skills shortages, lack of access to finance and customs procedures (an exception is as Tata Motors in automobiles)<29>. Nonetheless, data suggests a growing importance of Global South partners for India in GVC trade. The share of manufacturing foreign value-added in India’s domestic final demand originating from the European Union (EU) and North America declined in the 2005-2015 period, while that of China has significantly increased from 11.17 percent in 2005 to 28.35 percent in 2015 (see Figure 3). At the same time, domestic value-added by India’s manufacturing sector in foreign final demand (by partner shares) declined in the EU and North America, and increased in Brazil, China, South Africa and the Russian Federation, with the largest increase for China — from 4.2 percent in 2005 to 7.49 percent in 2015 (see Figure 4).

Data suggests a growing importance of Global South partners for India in GVC trade.

Figure 3: Manufacturing foreign value-added in India’s domestic final demand, by partner shares

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Figure 4: India’s manufacturing domestic value-added in foreign final demand, by partner shares

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

A 2016 study scoped out India’s potential to form its own GVCs through the identification of probable lead products<30>. Using the Harmonised System — an international nomenclature for the classification of products — the study identifies potential lead products for India, which include products like processed fish, cashew nuts, appliances, dyes, leather articles, footwear, carpets, women’s dresses, textiles furnishing articles, jewellery, machinery, turbines, transformers and tractors. It is estimated that the total potential market share in the identified lead products is around US$ 22.8 billion in addition to India’s existing exports, implying that there is a potential to increase total exports of lead products by 112 percent. It is estimated that in the US market, potential exports can rise by almost 120 percent in the lead products. In the UK, potential exports can increase by 125 percent. In EU, the exports of lead products have the potential to rise by 80 percent. However, this would require increasing the competitiveness of the lead products through potential GVCs led by India.

The 2016 study further identifies 20 least developed countries (LDCs) that are more cost-competitive as sources of inputs for India that the existing ones. These LDCs can together export around US$ 12 billion worth inputs into exports of India’s lead products. Additionally, 129 unique inputs at HS-6 digit have been identified that can increase India’s competitiveness in its GVCs of the identified lead products.

It is estimated that in the US market, potential exports can rise by almost 120 percent in the lead products.

Digitalisation: New pathways for export diversification

The technological capabilities, including digital, of Indian firms are key for export diversification, linking into GVCs and forming GVCs in the country. Digital technologies have opened up new pathways for export diversification along the value chains:

• Digitalisation of pre-manufacturing activities has led to reductions in costs and timelines for product development. For example, automotive firms in India, such as Hyundai Motors India Limited and Mahindra and Mahindra, initially specialised in manufacturing commercial and utility vehicles, but later developed capabilities to serve the passenger car segment through the use of digital technologies, which enabled higher output major changeover costs, with faster delivery time and higher quality<31>.

• Digitalisation of post-manufacturing activities, such as sales through e-commerce, has opened avenues for new products and sectors. Analysing market-related data, for instance, can enable designers to uncover the functionalities and features that customers particularly value, thereby identifying demand for specific products<32>. Similarly, big data analytics of online sales can enable firms to take a more targeted approach in product development, allowing for more profitable diversification. In Bangladesh, for instance, online trade is more diversified than offline trade<33>.

• Digitalisation and automation in manufacturing tasks can boost efficiency in the production process, leading to higher output and exports and more profits, which can be reinvested into the development of new and more sophisticated product lines.

Evidence from Indian firms suggests that investment in information technology (IT) and digital infrastructure positively impacts exports diversification, either directly or indirectly (through efficiency gains). A positive relationship between IT investment and export performance is seen in the Indian pharmaceutical industry<34>. Similarly, an analysis of several Indian manufacturing firms across sectors over the 2001-2015 period shows that increasing the share of digital assets in a firm’s infrastructure significantly and positively impacted firm-level export intensity<35>. The average product sophistication is also found to be 4 percent to 5 percent higher in digitally competent Indian GVC firms as compared to digital laggards<36>.

In the pharmaceutical GVC, India and China are major producers of APIs, together accounting for 31 percent of API manufacturing facilities in the world. Despite this, India imports around 70 percent of its APIs from China.

The Indian pharmaceutical sector has leveraged digitalisation to build resilience against the pandemic and future economic shocks. In the pharmaceutical GVC, India and China are major producers of APIs<37>, together accounting for 31 percent of API manufacturing facilities in the world<38>. Despite this, India imports around 70 percent of its APIs from China<39>. As a result, the Indian pharma sector was hit hard when the pandemic struck; Indian manufacturing firms reported a decline of between 20 percent to 30 percent in their capacity and a rise in the prices of APIs imported from China<40>. The adoption of digital technologies can transform the sector. The average export intensity and research and development intensity in Indian pharma firms that invest in digital capabilities is 45 percent and 2.7 percent, respectively, compared to 28 percent and 1.7 percent in firms that do not invest in digital capabilities, with average product sophistication also higher in digitalised pharma firms<41>. Given that pharmaceutical products dominate India’s exports to Africa, along with petroleum products, accounting for about 40 percent of total Indian exports to the African market, this could be Indian pharma’s big opportunity in Africa<42>.

Currently, India lags behind many developing countries in the digitalisation of manufacturing exports; the value added by digital services in India’s exports is largely concentrated in the computer, programming and telecommunication services sectors (accounting for 88 percent of total value added by digital services in exports<43>. The value added by digital services in manufacturing exports is 9 percent, much lower than in comparators — 78 percent in Turkey, 60 percent in China, 57 percent in Indonesia and 54 percent in Brazil<44>.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

The unfolding of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic have increased the challenges facing developing countries like India. Rising digitalisation is leading to loss of export competitiveness even as the pandemic is disrupting existing exports and imports. To face these twin challenges, India must reorient its trade policy to achieve V-shaped recovery and build resilience.

Attracting FDI in Indian manufacturing is key to upgrading existing GVCs, but more careful analysis is needed on the differential impacts of FDI by country-origin.

Targeted sector-level policies are needed to ensure firms are ‘gainfully’ linking into GVCs. For instance, backward GVC linkages (FVA in exports) can be boosted in those sectors where Indian firms are not competitive, and FVA can thus complement production, increase productivity and diversify firms rather than substituting or displacing existing domestic value chains. At the macro-level, there is a need for policies to facilitate the ease of doing business, improve trade logistics, address infrastructural challenges and last-mile connectivity to expand GVC linkages. India’s logistics costs continue to be triple that of China and double that of Bangladesh<45>. Attracting FDI in Indian manufacturing is also key to upgrading existing GVCs but more careful analysis is needed on the differential impacts of FDI by country-origin.

It is crucial to provide a conducive environment and right conditions for developing digital innovation and knowledge systems that can help linked Indian firms to climb up the value-chain ladder. Comprehensive innovation policies at the national level, along with adequate incentives in targeted sectors that are more linked into GVCs, can help achieve this. At the micro-level, the right incentives need to be created for firms to invest in their technological and digital capabilities, and for the development of Indian lead firms. This can help Indian micro, small and medium enterprises link with larger and more productive firms, further facilitated through digital platforms.

Successful and gainful integration and upgrading in GVCs can facilitate technology transfer and skills development in India. However, advancing digitalisation and bridging digital divide within the country is important. This can be achieved through domestic policies targeting infrastructure and communication technologies (ICT) development, investment in ICT goods and services, and investment in skills development of supplier firms, which can enable them to develop complementary competencies to the lead firms and move into more power symmetrical GVC linkages.

With the EU and other developed economies emphasising on their ‘industrial sovereignty,’ there is likely to be a shift in their existing GVCs, making them shorter and closer to the home countries of the foreign firms.

Further, digital servicification of manufacturing exports can increase the competitiveness of Indian firms and enable diversification. Policy interventions need to target the development of ‘soft’ digital infrastructure, such as cloud computing capabilities, data infrastructure and intellectual property networks capacity. Similarly, in services, there is potential to leverage sectors of electronic hardware, storage devices and computer services exports and diversify into high-quality information solutions<46>. To seize the rising opportunities, India must urgently invest in its digital competencies.

India must strategise to increase its export competitiveness. With the EU and other developed economies emphasising on their ‘industrial sovereignty,’ there is likely to be a shift in their existing GVCs, making them shorter and closer to the home countries of the foreign firms. This is an opportune moment for India to fill the gap. In sectors like appliances, leather articles, jewellery, machinery and others identified, India must take the lead and form its own GVCs through investment and joint ventures with partners in the Global South that can supply intermediate inputs at competitive rates. This will not only increase India’s export competitiveness but will also increase its export diversification.

Endnotes

<1> Rashmi Banga and Karishma Banga, "Digitalization and India’s Losing Export Competitiveness," in Accelerators of India's Growth — Industry, Trade and Employment, eds Suresh Chand Aggarwal, Deb Kusum Das and Rashmi Banga (Singapore: Springer, 2020), pp. 129-158.

<2> Banga and Banga, "Digitalization and India’s Losing Export Competitiveness"

<3> S.P Sharma and Ashima Dua, "Product and Market Diversification of India’s Exports,” Employment News Weekly, vol. 18 (3-9 August 2019), http://employmentnews.gov.in/newemp/MoreContentNew.aspx?n=Editorial&k=40239.

<4> Sharma and Dua, “Product and Market Diversification of India’s Exports”

<5> WITS, “UN COMTRADE,” World Bank, https://wits.worldbank.org/.

<6> UNCTAD Stat, “SITC rev.3 products, by technological categories (Lall (2000)),” UNCTAD, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/en/Classifications/DimSitcRev3Products_Ldc_Hierarchy.pdf.

<7> World Bank, “The World Bank in India,” World Bank Group, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/india/overview.

<8> Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Department of Commerce, Government of India, 2020, https://commerce.gov.in/press-releases/indias-merchandise-trade-preliminary-data-november-2020/.

<9> Arindam Majumdar and Sohini Das, “Coronavirus: Govt asks car manufacturers to explore ventilator production,” Business Standard, 25 March 2020, https://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/coronavirus-govt-asks-car-manufacturers-to-explore-ventilator-production-120032501475_1.html.

<10> Narayan V, “India's textile industry is crafting a future in global fashion mask market,” Hindu BusinessLine, 24 May 2020.

<11> “How India managed biggest data surge during Covid-19 lockdown?” Dataquest, 7 July 2020.

<12> Invest India, “Schemes for Electronics Manufacturing,” National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency of India.

<13> Press Information Bureau, Government of India, 2020.

<14> J.R. Baldwin and Beiling Yan, “Global Value Chains and the Productivity of Canadian Manufacturing Firms,” Statistique Canada, no. 090 (2014).

<15> P. Kowalski et al., “Participation of Developing Countries in Global Value Chains, Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policies,” OECD Trade Policy Papers, no. 179 (2015).

<16> R. Veugelers, F. Barbiero and M. Blanga-Gubbay, “Meeting the Manufacturing Firms Involved in GVCs,” in Manufacturing Europe’s Future, ed. R. Veugelers (Brussels: Bruegel, 2013).

<17> Rashmi Banga, Gainfully Linking into Global Value Chains: Experiences and Strategies, (GlobeEdit, 2019)

<18> Saon Ray and Smita Miglani, “India’s GVC integration: An analysis of upgrading efforts and facilitation of lead firms,” ICRIER, working paper 386 (2020).

<19> Ricardo Hausmann, Jason Hwang and Dani Rodrik, "What you export matters," Journal of Economic Growth 12, no. 1 (2007): 1-25.

<20> Karishma Banga, “Global Value Chains and Product Sophistication: An Empirical Investigation of Indian Firms,” CTEI, Working Paper no. 2017-15 (1 December 2017).

<21> Gary Gereffi, John Humphrey and Timothy Sturgeon, "The governance of global value chains," Review of International Political Economy 12, no. 1 (2005): 78-104.

<22> Gereffi et al., “The Governance of Global Value Chains”

<23> Katharina Eck and Stephan Huber, "Product sophistication and spillovers from foreign direct investment," Canadian Journal of Economics 49, no. 4 (2016): 1658-1684.

<24> Bishwanath Goldar and Karishma Banga, "Country origin of foreign direct investment in Indian manufacturing and its impact on productivity of domestic firms" in FDI, Technology and Innovation, (Singapore: Singapore, 2020), pp. 13-55.

<25> OECD-WTO Trade, “Trade in Value Added (TiVA): Principal indicators’” OECD.Stat.

<26> Rory Horner and Khalid Nadvi, "Global value chains and the rise of the Global South: unpacking twenty‐first century polycentric trade," Global Networks 18, no. 2 (2018): 207-237.

<27> Stephanie Barrientos, Peter Knorringa, Barbara Evers, Margareet Visser and Maggie Opondo, "Shifting regional dynamics of global value chains: Implications for economic and social upgrading in African horticulture," Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48, no. 7 (2016): 1266-1283.

<28> Giovanni Pasquali, Shane Godfrey and Khalid Nadvi, "Understanding regional value chains through the interaction of public and private governance: Insights from Southern Africa’s apparel sector," Journal of International Business Policy (2020).

<29> Ray and Miglani, “India’s GVC integration”

<30> Rashmi Banga, “Boosting India’s Exports by Linking LDCs into India’s Potential Global Value Chains,” Commonwealth Secretariat, 2016.

<31> Saon Ray and Smita Miglani, Global value chains and the missing links: Cases from Indian industry, (Taylor & Francis, 2018).

<32> Jörg Mayer, “Digitalization and industrialization: Friends or foes?” UNCTAD Research Paper no. 25, (2018).

<33> “What Sells in E-commerce: New Evidence from Asian LDCs,” International Trade Centre, April 2018.

<34> Savita Bhatt, “Information Technology Investments and Export Performance of Firms: A Study of Pharmaceutical Industry in India,” FKGS Conference, 2015.

<35> Banga and Banga, "Digitalization and India’s Losing Export Competitiveness"

<36> Karishma Banga, “Digital Technologies and Product Upgrading in Global Value Chains: Empirical Evidence from Indian Manufacturing Firms,” The European Journal of Development Research (2021), pp.1-26.

<37> Eric Palmer, “Concern for drug shortages grows as COVID-19 outbreak drags on,” Fierce Pharma, 14 February 2020.

<38> U.S. Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Government, 30 October 2019.

<39> “India's dependence on China for APIs exposes vulnerabilities in pharma: Jairam Ramesh,” Business Today, 19 August 2020.

<40> G Naga Sridhar, “Lockdown : Pharma, medical devices units working only at 20-30% capacity,” The Hindu BusinessLine, 10 April 2020.

<41> Karishma Banga, “3 ways digital technology can help drug makers fight COVID-19,” World Economic Forum, 21 July 2020.

<42> Oommen Kurian and Kriti Kapur, “Covid-19 outbreak could be Indian pharma’s big opportunity in Africa,” Quartz India, 2 April 2020.

<43> Banga and Banga, "Digitalization and India’s Losing Export Competitiveness"

<44> Banga and Banga, "Digitalization and India’s Losing Export Competitiveness"

<45> World Bank, World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains, World Bank Group, 2020.

<46> Rahul Anand, Kalpana Kochhar and Saurabh Mishra, “Make in India: which exports can drive the next wave of growth?” IMF Working Papers no. 15-119, International Monetary Fund (29 May 2015).

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: Author, constructed from the World Integrated Trade Solutions database

Source: Author, constructed from the World Integrated Trade Solutions database Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development- World Trade Organisation

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development- World Trade Organisation Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Source: Author, constructed from the Trade in Value Added database, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development PREV

PREV