-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

It is about recognising that while cities offer economic opportunities to millions, they come with poor and overcrowded housing, lack of safe water and sanitation, lack of education and primary healthcare, high risk of disasters and climate change events.

This article is part of the series — Colaba Edit.

The COVID-19 pandemic, many believe, was the major story and prime disruptor of human life in 2020. But this is only partially correct. For anyone with a passing knowledge of urban affairs, the big story lay in what the pandemic unravelled about our cities and their inadequacies, a revelation that did not conform with the idea of cities as the power engines of the modern (or post-modern) world.

At least two truths stare at us from shiny First World or chaotic Third World cities — one, cities may be formidable economic engines for their nations’ economies, but they have not become home to millions who migrated for work; and two, in a crisis like the pandemic, it is the much-maligned urban public infrastructure that has become the rescuer-deliverer-redeemer beyond the celebrated private sector.

Knowing these, besides the other challenges, it will be foolish to simply go back to business as it were to discuss policymaking for cities, debate approaches to urban environments and join forces on global forums. Cities across the world were theatres of a pandemic not witnessed in over a century. It showed the hollowness of certitudes about cities, urban planning and design, resilience and sustainability, technology and smart cities that had fuelled conversations for the last 25 years.

In 2021, a discussion on cities must include the inescapable impact of the pandemic and those it hit the hardest — some recorded by media and citizens, the rest falling in between crevices of public and personal domains — but must necessarily go beyond. This forces us to ask a set of questions, such as what or who makes cities and sustains them, what ruptures them and where do the fault-lines lie. This must be followed by a second set of questions on who plans cities and for whom, how they are planned, and what policies lead us to cities that are mostly a living hell for millions and turn into desolate concrete spaces in crises. So, have our cities largely failed us and has urban policymaking come a cropper?

Even a hesitant nod in the affirmative to these questions should make it clear that urban policymaking that guided the world in the last hundred years — more robustly and globally since the late 20th century — is due for a revision and rethink. What is called for is a rethink on at least three aspects: a) cities imagined and built only as economic centres of neo-liberal economies; b) policymaking for cities that has mostly revolved on the sustainability-technology-resilience paradigm; and c) the mind-boggling array of forums that between them have not ensured life of dignity to millions in the world’s cities.

The numbers are staggering. An estimated 55.3 percent of the world’s population lived in urban settlements in 2018, according to the United Nations; this is projected to be 60 percent by 2030. One in every three persons in the world will live in cities with at least half a million citizens, 28 percent will live in cities with more than a million, and the world’s megacities (cities with at least 10 million) are expected to cram in 752 million or roughly nine percent of the world’s population by then, states the UN.

It is not sufficient to merely have forums, and there is no dearth of global policy institutions and think-tanks on urban issues. It is necessary to ask hard questions of them and force them to rethink. It is important to call out their mistakes, nudge them to embrace a new way of discussing, making and sustaining cities. It is critical to go beyond private interests and profit motives in making cities. Why, for example, do urban policymaking forums not place ideas of equality and humanity at the very centre of all policy and planning? Why is inequality — obscene levels of inequality in access to life-essential services, opportunity and wealth — taken as a sine qua non for urban development? Is it even development if millions are left out?

Hardly any purpose will be served in establishing yet another global policymaking forum for cities when the existing ones, both in the developed North and developing South, cover vital areas such as health, education, transport, land use, infrastructure, heritage conservation, poverty, climate change and sustainable development. They comprise many variants of the UN, philanthropic entities with vast influence, private institutions, dedicated universities and schools, niche and non-governmental organisations, and more, all with an overarching influence across the world. Naming even a few of them makes for a veritable word salad. If urban policy and planning through such institutions has left a legacy of mostly uninhabitable, unequal, unsustainable cities for millions, does the world really — honestly — need another global forum?

It will be in the fitness of things to repurpose and realign a few existing forums to go beyond their clichéd frameworks and delve beyond their tired paradigms, to remake our cities to be inclusive and sustainable for the largest number who live in them. Cities and city-making need more participatory democracy, not less. Urban policy must not be devised behind closed doors based on the dogma of a self-appointed few; it must be participatory and evolve bottom-up, based on consultations with those it most affects and pivoted to local or regional requirements. To assume that a new forum will somehow magically steer us in this direction is to be childishly naïve. It makes more sense to reorient the existing ones to be more participative, democratic and inclusive than they have been.

This, then, is hardly about a forum or the jargon of urbanism it adopts, the symposia it organises and reports it spews out. It is about the politics and vision of a forum — new or existing — that seeks to make cities more inclusive and sustainable for millions. It is about a fundamental reimagination of cities, an imagination that goes beyond gated communities and islands of opulence linked by toll roads amidst crumbling public infrastructure and squalid informal housing. It is about going beyond the framework of cities as markets, points of exchange of capital and labour, sophisticated finance and banking.

Urban theorist Saskia Sassen identified a global city, in her work of 1991, as a major node in the inter-connected systems of information and money beyond national boundaries, making global cities of our era dramatically different from the great cities of the 19th century. The downside of this has meant the disintegration of the public space, pools of squalor, wide disparity and more.

It is time to recognise urban poverty as an endemic reality, even an outcome of global city-making policies, and speak up about and for the urban poor, a class whose numbers are projected to rise after COVID-19 by even World Bank’s estimates. It is about recognising that while cities offer economic opportunities to millions, they come with poor and overcrowded housing, lack of safe water and sanitation, lack of education and primary healthcare, high risk of disasters and climate change events. The poorest urban children are more likely to die before their fifth birthday than the poorest rural children in most countries, UNICEF told us in 2018.

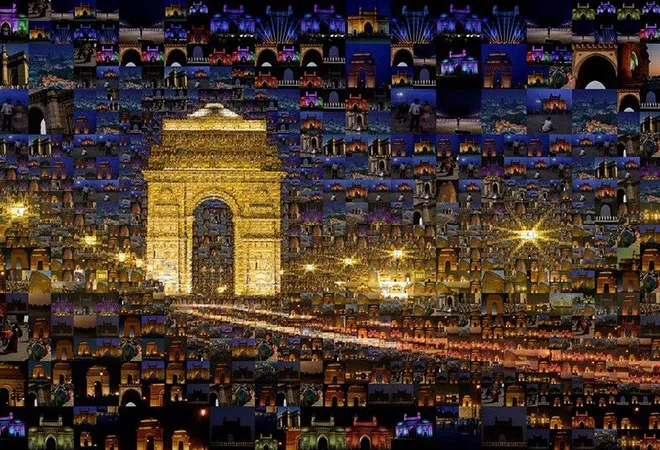

Cities, then, are far more than hubs of commerce and private enterprise. Policymaking discussions, especially in 2021, must begin at this point. By the end of this decade, Delhi is projected to be the world’s largest city by population and Mumbai the sixth largest. The question to ask is not how wealthy they will be but how to build them as socially inclusive, equitable and vibrant cities.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Smruti Koppikar Mumbai-based independent journalist essayist and city chronicler writes at the intersection of urban issues politics technology gender and media. She worked in senior ...

Read More +