-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

There is an urgent need for RUTA to enhance regional transport planning, connectivity, and promote inclusive, sustainable mobility solutions across urban and rural areas

Image Source: Getty

As India’s urban populations continue to rise, its mobility landscape is experiencing a profound transformation. The shift is evident in the rise of cities with populations of more than 500,000—from 100 in 2011 to 150 in 2023, accommodating an additional 150 million inhabitants.

A glaring disparity has emerged between the major metropolises and their smaller and medium-sized counterparts: While the transport systems of large cities benefit from technical capacities and bureaucratic support, smaller urban centres are struggling to rejuvenate theirs. In the small and medium-sized cities, the support is limited to national schemes such as the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and the Urban Infrastructure Development Scheme for Small and Medium Towns (UIDSSMT).

A glaring disparity has emerged between the major metropolises and their smaller and medium-sized counterparts: While the transport systems of large cities benefit from technical capacities and bureaucratic support, smaller urban centres are struggling to rejuvenate theirs.

If India aims to become a US$5-trillion economy in the next three years, seamless and robust public connectivity would be among the prerequisites. However, the absence of efficient State Transport Undertakings (STUs) and private operators-run local intracity and mofussil bus services[1] at a regional level has resulted in the dominance of private modes of transportation. Analysis by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) indicates that in 2018, car registrations increased by 35 percent and two-wheeler registrations by 98 percent compared to 2010. While private vehicles may address immediate mobility needs, the inclination towards using these modes worsens congestion, increases emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) and pollutants, and adds to India’s fuel import dependence.

The transport sector is a significant contributor to India’s GHG emissions and is the fastest-growing source of nitrogen oxides (NOX) in the country. This challenge leads to substantial health and welfare losses, currently estimated by the World Bank at 7.7 percent of India’s GDP.

Therefore, development strategies to foster equitable growth across all tiers of cities and rural areas demand a bold regional approach. Such a framework encompasses transportation solutions and institutional reforms to ignite decentralised, integrated initiatives.

As urbanisation becomes more rapid, the urban continuums along highways and railways are blurring the administrative boundaries between cities, semi-urban areas, and rural areas. A symbiotic relationship exists between the rural and urban regions, with the latter increasingly becoming the focal points of economic activity and opportunity, resulting in a significant spike in migration trends towards megacities and state capitals.

With metropolises and megacities fast approaching their population thresholds, an analysis of the Census 2011 data and the trends in the past decade shows that small towns are urbanising at a rapid pace. For example, a 2020 Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) survey ranked Kerala’s Malappuram as the world’s fastest-growing city, recording a 44.1-percent population growth rate from 2015 to 2020. Kozhikode (34.5 percent growth) and Kollam (31.7 percent) in Kerala were the other two Indian cities ranked among the world’s top ten fastest-growing cities. Overall, too, smaller and medium-sized city areas grew by 31 percent between 2001 and 2011. The growing predominance of these smaller urban areas will make it even more difficult for them to balance the trade-offs between job availability and the provision of services and utilities, including affordable housing.

A symbiotic relationship exists between the rural and urban regions, with the latter increasingly becoming the focal points of economic activity and opportunity, resulting in a significant spike in migration trends towards megacities and state capitals.

On the other hand, although the urban economic output has overtaken that of the rural economy, overall urban employment remains less than half of that in the rural regions. Consequently, despite rural areas contributing 70 percent to the total workforce, India experienced a decline in job generation in these districts. Therefore, to foster a balanced approach between cities, towns, and rural regions, it is essential to not segregate urban and rural mobility planning within the same region.

Evidence from the National Sample Survey Office’s Household Consumption Expenditure Survey 2022-23 indicates higher expenditures on private modes and higher travel costs for both urban and rural areas. For example, of the 14 percent monthly per-capita consumption expenditure in both rural and urban areas, expenses towards conveyance (travel fare and fuel) exceeded the spending on education and healthcare. Further, rural areas, which are generally underserved in transport connectivity, pay more than their urban counterparts.

Mobility planning must therefore transcend traditional boundaries and integrate intra-city and regional transport for inter-towns and rural areas. Though India’s rural areas are governed under district panchayats or zilla parishads, and urban areas are under municipal councils or municipal corporations, mobility planning must be integrated under a single agency. This would ensure seamless connectivity with similar service levels. Leveraging economies of this scale will streamline and rationalise the operational costs for transit services and make it more cost-effective for users across India. Further, technical expertise from large cities can be leveraged for progress in small towns and rural areas.

Several central government policies, schemes and programmes—such as the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (2005), the National Urban Transport Policy (2006), and the National Metro Rail Policy (2017)—have repeatedly highlighted the urgent need for city-level Unified Metropolitan Transport Authorities (UMTAs). Only a handful of cities, however, have attempted to constitute such a body, and the few active UMTAs are unable to integrate regional mobility planning needs. The concept of UMTA, which remains largely ineffective in building the desired level of synergy among various transport agencies, must evolve to accommodate the transport needs of small- and medium-sized towns in the region as well as inter-city, and rural areas. This article recommends that the existing UMTA framework evolve and transition into the Regional Unified Transport Authority (RUTA).

The concept of UMTA, which remains largely ineffective in building the desired level of synergy among various transport agencies, must evolve to accommodate the transport needs of small- and medium-sized towns in the region as well as inter-city, and rural areas.

By expanding the purview to a more extensive jurisdiction area, RUTA can effectively navigate the interdependence of rural, metropolitan areas and nearby small and medium-sized towns. Such an expanded scope can foster greater connectivity and accessibility across a spectrum of habitats, thereby enhancing mobility at the regional scale. RUTA can leverage its technical expertise to fulfil the mandates effectively and, most significantly, bridge the gaps in urban transport infrastructure.

Furthermore, RUTA fosters cross-boundary and cross-agency coordination for faster project implementation, traffic management, and other accessibility concerns. It can navigate competing interests effectively, such as prioritising mobility enhancements while mitigating emissions. It can emerge as the guiding force, championing solutions that strike a balance between diverse stakeholder needs for the collective benefit of urban and ‘rurban’ populations alike. Additionally, RUTA can streamline transport budgets to ensure just and inclusive spending, leading to decentralised development.

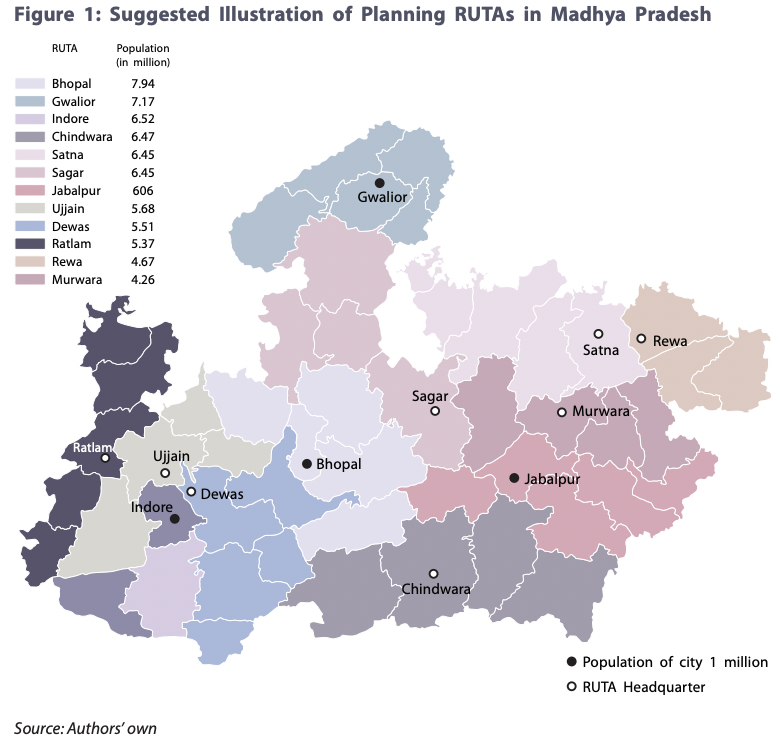

Formed at the state level, RUTA must consider all regions mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (MECE). Each region must have a distinct mobility interdependence with at least one million- plus city or a large economic hub or urban continuum. States can explore the development of RUTA boundaries based on proximity to the hub, its development policies and focus, overlapping administrative district boundaries, and RTOs.

For instance, according to the 2011 census, Bhopal, Indore, and Jabalpur are three million-plus cities in Madhya Pradesh. Urban centres like Ratlam, Ujjain, and Dewas often receive less attention due to their non-metro status. Instead of Indore as a standalone UMTA, the RUTAs, covering 4-7 million population regions, would address the needs of all cities, towns, and rural areas for more holistic planning.

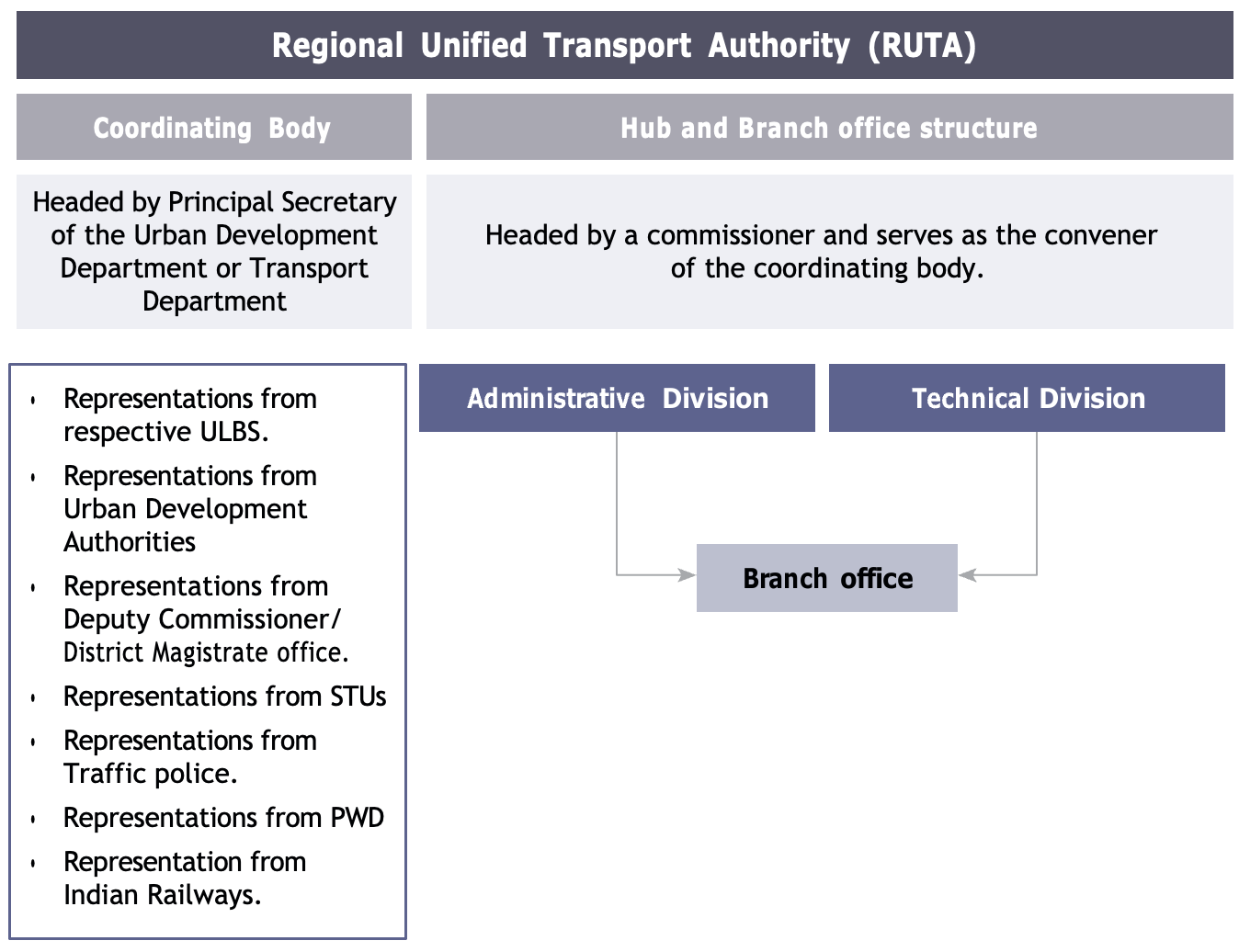

States must envision RUTAs as overarching entities to develop vision and strategic planning across the region, transcending the confines of traditional metropolitan boundaries. The staffing pattern proposed in UMTA operational guidelines must be adequately revised to include small-medium town representatives, block development officers, and zilla parishad officials. The proposed RUTAs must specifically focus on public transportation and freight planning, with responsibilities in coordinating with state-level agencies and local authorities. RUTAs may establish hub offices in large cities, with branch offices across regions for efficiency and outreach. RUTAs can be pivotal in managing transport budgets, funding projects, and overseeing their implementation. Moreover, RUTA can take the role of technical capacity building and monitoring for districts and smaller towns.

The RUTA offices must have administrative and technical divisions. Oversight can be provided by a coordinating body chaired by the Principal Secretary of the Urban Development Department or Transport Department, with representatives from STUs, Urban Local Bodies, District Collector, Public Works Department, and the traffic police. A commissioner must head RUTA, serving as the coordinating body’s convener. Meanwhile, the technical section, housed within RUTA, must focus on planning, project implementation, and building technical capacity for small-medium towns.

Source: Authors’ own

RUTA can integrate and consolidate fragmented mobility and transport governance while retaining local participation. It will also ease the implementation of state-level policies and programmes, such as EV policies, bus programmes, low-emission zones, scrapping mandates and related public information outreach. Fewer administrative delays and better coordination will substantially fast-track and ease the execution of decisions and projects. The regional confluence will ease synced public transit planning, optimise operations costs, and facilitate private sector participation due to consolidated mobility services markets. RUTA will help rethink India’s mobility planning to be more just, equitable, and inclusive.

This essay is part of a larger compendium “Policy and Institutional Imperatives for India’s Urban Renaissance”.

Himani Jain is a Senior Programme Lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW)

Sourav Dhar is a Programme Lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW)

The authors acknowledge the support provided under the ‘Cleaner Air & Better Health’ project of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

[1] These are short-distance bus routes connecting cities with nearby towns, villages, and other non- urban regions.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Himani Jain is a Senior Programme Lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) ...

Read More +

Sourav Dhar is a Programme Lead at the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) ...

Read More +