As the economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic reveals itself, Russia has set a deadline of 1 June for the formation of a national economic recovery plan. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that the pandemic will result in the Russian economy contracting by 5.5 percent before achieving economic growth of 3.5 percent in 2021. Till now, the economic stimulus announced by the Russian government stands at roughly 2.8 percent of the GDP, leading to criticisms of an inadequate response, with some economists calling for spending between seven to 10 percent of the GDP to cope with the crisis.

The economic cost of the pandemic

As a result of the lockdown measures imposed to deal with the rising number of coronavirus cases, the government estimates at the beginning of the month showed that total economic activity had declined by a third since the pandemic began. Already, unemployment has risen by 30 percent since the pandemic hit Russia, according to official statistics, but the figures are believed to be vastly underestimated. This is due to the existence of a large informal sector that is estimated to be between 30-40 percent of GDP.

The regions are facing the threat of ‘highest budget deficits’ in two decades due to a loss of revenue owing to the economic slowdown and the crash in energy prices. It has been argued that support from the central government will not be enough to plug the gap. Efforts at the regional level to contain the economic damage and open businesses have been made difficult due to rise in number of COVID-19 cases.

Given the role energy exports play in Russian economy, the low demand and price crash is a worry for the Russian government.

Apart from dealing with the consequences of a national-level slowdown, Russia will have to formulate its recovery plans amid a worldwide recession and a crash in commodity prices due to reduced demand, leading to a loss of revenues from oil and gas exports. Given the role energy exports play in Russian economy, the low demand and price crash is a worry for the Russian government.

Even after 2014, when Russia faced sustained Western sanctions, its overall impact on the economy was worsened due to the declining oil prices at the time. Although experts note that it is difficult to separate the impact of the two events, the effect of sanctions is estimated to be comparatively lower than that of the oil price shock. And this was at a time when oil prices were still at $80 a barrel towards the end of 2014, coming down from a high of around $115 in June. Now, the Urals crude is hovering at $35, lower than the $57 on the basis of which the Russian budget was prepared for 2020.

Fearing a sustained period of low commodity prices, Russia currently is demonstrating great care in use of its $157 billion National Welfare Fund. Created as a rainy-day fund, it was set up in order to compensate for loss in tax revenue from oil exports if the prices slip below $42 a barrel. There are strict rules regarding spending of this Fund and the government has maintained caution, despite calls for the reserves to be utilised to give direct benefits to struggling businesses and citizens. In addition to the welfare fund, Russia has built up substantial reserves and maintains a low public debt, which gives it the ability to add to its stimulus plan in the coming days.

Fearing a sustained period of low commodity prices, Russia currently is demonstrating great care in use of its $157 billion National Welfare Fund.

A lot of decisions will ride on whether oil and gas prices recover in the coming months or not. The IMF estimates that oil exporting countries will have to deal with prices below $45 till 2023, and Russia has indicated that oil at $42 a barrel is a level Russia is comfortable with. However, at this point, costs of low commodity prices will be compounded by loss of economic activity due to the spread of the pandemic domestically, ‘tighter global financial conditions, and weaker external demand.’ There is also the uncertainty about when full economic activity will be restored and what changes would need to be brought to the existing business models in order to keep the workforce safe while keeping the economy going.

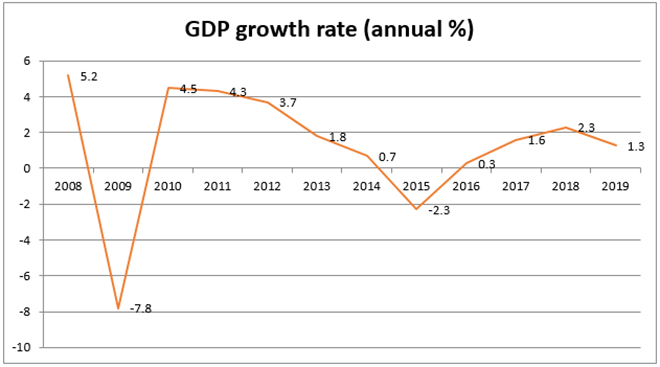

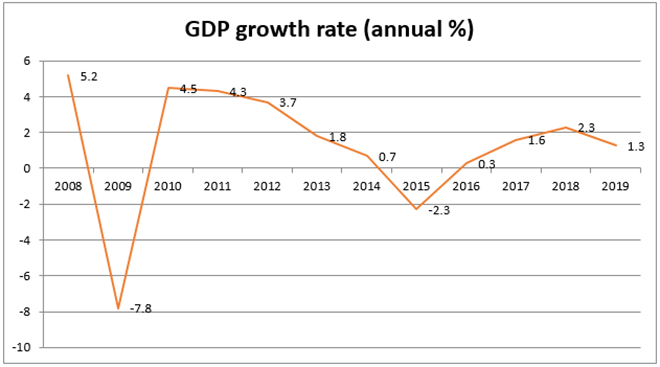

The global recession comes at a particularly bad time for Moscow, given that the economy had only begun to stabilise sometime in 2016 and modest signs of recovery were visible as energy prices inched higher aided by ‘a flexible exchange rate regime, and sizeable foreign exchange reserves.’ But the pandemic has destabilised this fragile recovery of an economy that was already growing at a relatively modest pace. The growth projection for Russia before the pandemic hit was at 1.8 percent for 2020, lower than the global growth projection of 2.9 percent.

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

The case for structural reforms

This low growth despite the strong macro-economic conditions of Russia — characterised by a low level of debt, high reserves and surplus budget — has been blamed on a lack of ‘systemic reforms.’ These include slow economic diversification, high state involvement in the economy, corruption, weak rule of law for business environment and a declining population.

While these issues remain unresolved, the Russian government in 2018 announced $400 billion worth national projects focusing on 13 main areas like health, education, infrastructure, housing, demography, environment, SMEs, exports, digital economy, etc. Faced with a significant decline in foreign investment due to western sanctions and plagued by economic stagnation, these projects were slated to be the growth driver for the economy in the coming years. But the slowdown, which will necessitate government spending in several sectors to shore up the economy, has raised questions about the ability of the state to invest in these projects as per the earlier plan.

Faced with a significant decline in foreign investment due to western sanctions and plagued by economic stagnation, these projects were slated to be the growth driver for the economy in the coming years.

Also, these projects will need to go hand-in-hand with structural reforms if they are to have a positive impact on Russian economy. As head of the audit chamber Alexei Kudrin has suggested, there is a need for ‘long-term sustainable improvement’ that would lead to ‘income growth, innovative economy and adequate state institutions.’ Apart from reducing its heavy dependence on energy exports, other suggestions have included a reform of the judicial structure, law enforcement reform, protection of property rights, dealing with corruption and creating the right business and investment climate to promote entrepreneurship.

Foreign policy costs

Russian analysts have long expressed concern about the slow pace of social and economic development in the country, in sharp contrast to the active decision-making when it comes to foreign policy decisions. As personal incomes of people decline and structural problems being faced by the economy remain unaddressed, it has impeded the development of wide-ranging bilateral relationships with Russia’s partners, who are eager to strike deals with economically stronger countries that can help in realization of domestic developmental goals. In other words, as Sergei Karaganov has noted, ‘Russia has a small market to attract allies and few opportunities to “buy” them.’

As emerging powers continue to gain in strength, Russia will have to deal with the presence of economically strong powers in areas where it is seeking to expand its influence – most prominently, Eurasia. This disparity between ‘Russia’s ambitions and capabilities’ remains a major cause of concern, primarily in the economic domain. At the centre of its Greater Eurasian vision is an economic body — the Eurasian Economic Union — one to which Russia contributes 90 percent of the GDP. A poor economic performance from the leading economy in the Union will have a direct impact on its overall fortunes. Already, China has become an important player in Eurasia and if it is able to further expand its presence in the region as West grapples with a growing coronavirus crisis within its boundaries, Russia will have to evaluate the overall impact on its position on the ground.

At the centre of its Greater Eurasian vision is an economic body — the Eurasian Economic Union — one to which Russia contributes 90 percent of the GDP. A poor economic performance from the leading economy in the Union will have a direct impact on its overall fortunes.

In addition, a further deepening of dependence on China economically as Moscow deals with the slowdown will pose uncomfortable questions about the position Russia will take in case of a rise in US-China rivalry. This is because as has been noted, any risk of ‘geopolitical mishaps’ exposing ‘economic weakness’ runs high.

A need to diversify relations with other regional powers to cope with the weaker economic position has been suggested as a way to keep the Russia-China relationship on an even keel, besides having the obvious advantage of strengthening the Russian position in Eurasia. With this objective, Moscow has in recent times sought to galvanise its ties with other players including India, ASEAN, Japan and South Korea. The impact of the recession on Russia at this particular moment in geopolitical history will impact its foreign policy trajectory in very specific ways. In order to establish itself as a key player in Eurasia, Moscow will need to build its domestic economic strength — a prospect that requires deep seated reforms that will affect the established elite power structures existing within the political and economic system of Russia. Whether the pandemic will provide the push to carry out the necessary structural economic reforms in Russia remains to be seen.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank PREV

PREV