In the past two decades, Sino-Cambodian bilateral relations have shifted from a primarily military partnership to a multifaceted one encompassing trade, development finance, military ties, security cooperation and deepening people-to-people ties. These developments were facilitated by the current Cambodian Prime Minister’s deepening relationship with the Chinese government, BRI cooperation between the bilateral partners, and Cambodia’s deteriorating ties with the United States (US). The involvement of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in financing and constructing the Cambodian Ream Naval base since 2020 and the subsequent presence of two Chinese naval warships since December 2023 is a key example of the deepening Sino-Cambodian relationship. It is also noteworthy that the Cambodian government demolished four US and Australia-backed structures in the naval port before the Chinese navy commenced port development.

The Ream Naval base holds geostrategic and geopolitical significance for China. It is close to the Malacca Strait, a critical chokepoint through which 70 percent of China’s energy imports come. China’s strategic infrastructure development in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea is also part of its increasing power projection in a region which it claims as its territory. Developing strategic infrastructure is also aimed at hedging against the US security architecture in Southeast Asia and India in the Indian Ocean region.

The Ream Naval base holds geostrategic and geopolitical significance for China. It is close to the Malacca Strait, a critical chokepoint through which 70 percent of China’s energy imports come.

This article analyses China’s strategic infrastructure development through the BRI in Cambodia and delineates its geopolitical and geostrategic implications.

China’s economic footprint in Cambodia

Cambodia and China signed their BRI cooperation agreement in 2013 at the first BRI Summit in Beijing. Since then, China has invested, loaned, and contracted projects worth US$15 billion in Cambodia. Transport and energy sector engagements between 2013 and 2023 comprised 68 percent of total BRI engagement in Cambodia, at US$ 8.1 billion and US$ 3.75 billion respectively. While China has faced backlash from the Cambodian people over cost overruns, displacement and low rate of employment generation due to the BRI, the Cambodian government has supported the expansion of BRI in Cambodia. After 10 years of BRI, China is the Southeast Asian nation’s largest development partner (US$ 20 billion) and creditor (US$7 billion). So much so, that Chinese FDI (US$ 2.46 billion) and aid comprise 50 percent of total inward investment (US$ 4.92 billion) and 84 percent (US$ 2.31 billion) of total aid (US$ 2.76 billion) to Cambodia in FY23. Coupled with being Cambodia’s largest trading partner since 2007, the balance of payments skewed heavily in Beijing’s favour. In 2023, China-Cambodia trade amounted to US$ 10 billion, with Chinese exports accounting for US$ 8.2 billion.

These data figures delineate a pattern of Cambodian economic dependency on China. However, this is a dependency that the Cambodian government willingly created.

These data figures delineate a pattern of Cambodian economic dependency on China. However, this is a dependency that the Cambodian government willingly created. There are several reasons behind this. Cambodia does not have a territorial dispute with China in the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, Cambodia’s government and the royal family have shared close and deep ties with the Chinese Communist Party, since the times of Mao Zedong and China’s immense economic footprint in Cambodia, so much so that collectively China’s outstanding loans (US$ 7.5 billion) and ongoing and finished investments (US$21.23 billion) between 2010 and 2023 amount to 64 percent of Cambodia’s nominal GDP (US$ 45.15 billion).

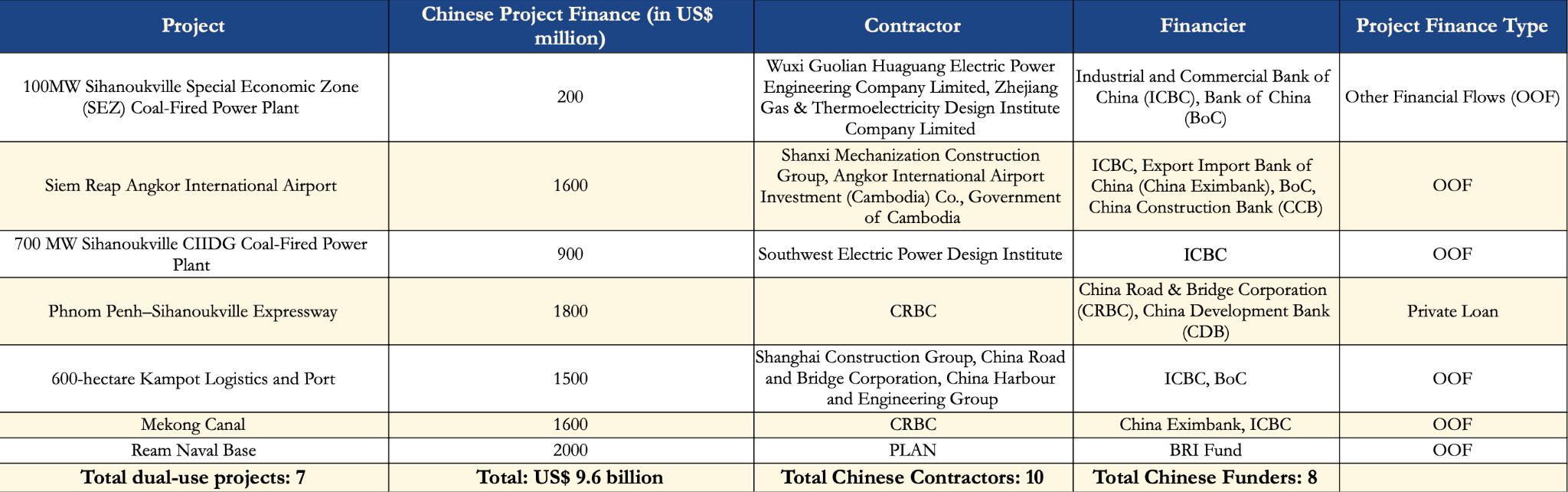

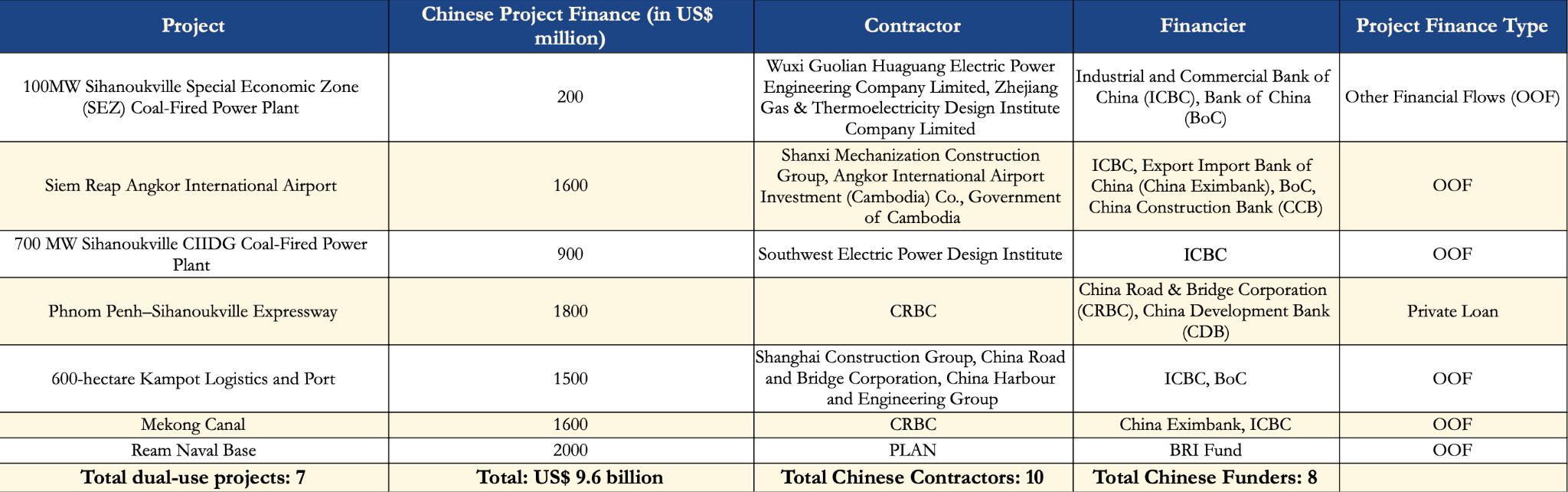

Table 1: China’s Dual-use Overseas Infrastructure in Cambodia

Source: AidData

Owing to these multifaceted and deep ties, China’s BRI strategy in Cambodia focuses on building dual-use infrastructure to promote President Xi Jinping’s idea of ‘civil-military’ fusion to augment China’s military capabilities. A mandatory requirement for BRI projects in numerous recipient nations is for Chinese overseas projects to meet military standards. Of the US$ 15 billion invested under the BRI, China-funded projects worth US$ 9.6 billion have followed dual-use implementation methodologies in their construction (see Table 1). These projects include two airports, one road network, one canal, two ports and two power plants. These are mainly built by 10 Chinese state-owned companies and financed by eight Chinese state policy banks (see Table 1). Instances of dual-use infrastructure include—the Techo canal, which connects Phnom Penh city to Kampot, Ream and Tek ports on the Gulf of Thailand, bypassing Vietnam's traditional hold on the mouth of one of Asia's biggest waterways, has raised regional suspicions that the canal can grant Chinese navy access to the interiors of the Cambodian and Vietnamese mainlands. Similarly, China-built and renovated airports have long, wide runways for fighter jets to land and take off. Commercial ports have also been renovated and built to accommodate berths deep and wide enough for accommodating warships.

Owing to these multifaceted and deep ties, China’s BRI strategy in Cambodia focuses on building dual-use infrastructure to promote President Xi Jinping’s idea of ‘civil-military’ fusion to augment China’s military capabilities.

Moreover, five out of seven projects are in the Sihanoukville SEZ (see Table 1), owned by a consortium of four Chinese state companies and one Cambodian company, consolidating Chinese influence in the Cambodian province. These developments have raised concerns in Hanoi and Washington DC, which are China’s regional rivals in the Gulf of Thailand, and China’s encroaching influence is perceived as detrimental to their own.

Beijing’s geopolitical motivations and Cambodia’s hedging foreign policy

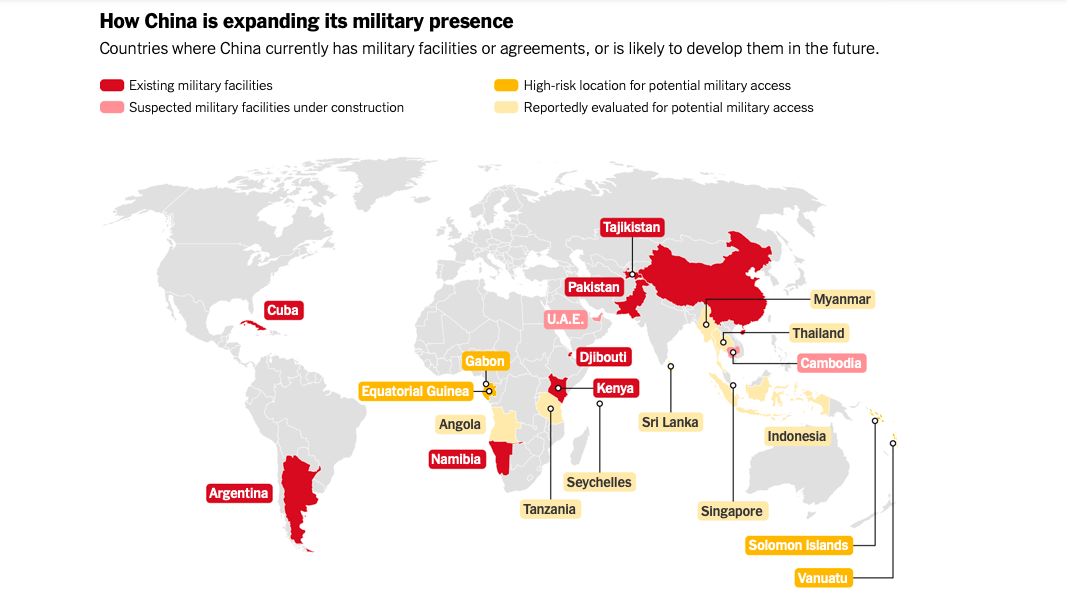

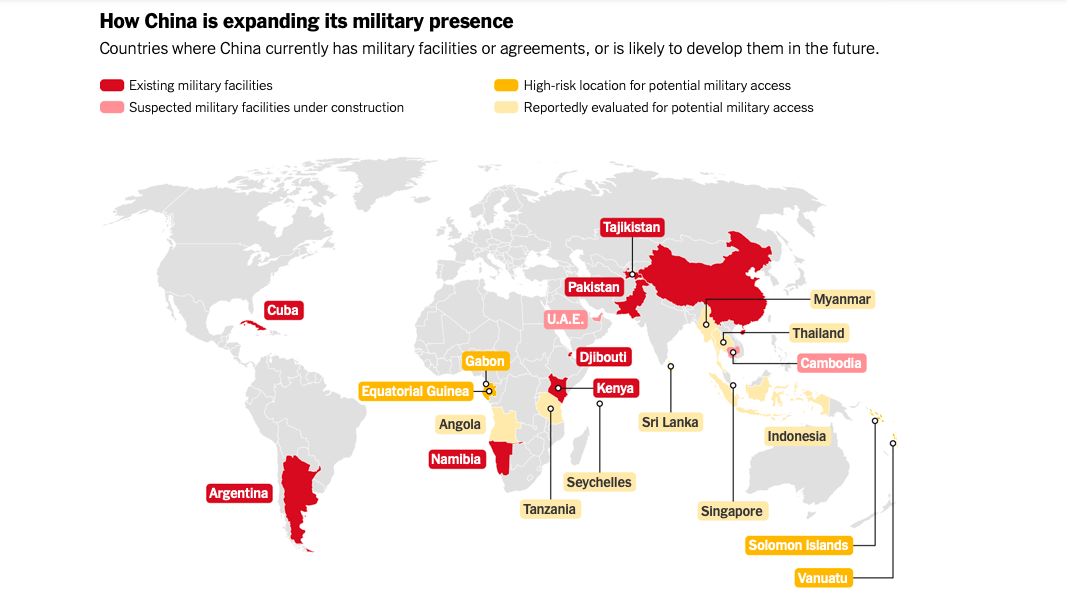

After 2017, China’s strategy was to benefit from the vacuum left by the US, fill it with BRI-linked economic investment, political support, and aid, and use closer economic relations to build strong defence cooperation. Beijing saw the worsening relations between Phnom Penh and Washington as a signal to hedge its bets, pushing more investments in a country with a strategic location in the South China Sea. Amidst these developing relations, most BRI projects have been mired with opaqueness and irregularities, mimicking Beijing’s dual-use investment strategy in Pakistan, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Sri Lanka, and the Pacific Islands (See Figure 1). China has not outrightly rejected the acquisition of the Ream Naval base; rather it has used Cambodia’s sovereignty card to divert attention from its dual-use infrastructure investments. It is likely that these investments are strategic and meant for logistic support as the threat increases in the South China Sea.

Figure 1: China’s expanding overseas bases

Source: Foundation of Defense of Democracies

Conversely, for Cambodia, increasing investments from China is a way to ensure continuous investment flows into its growing economy while maintaining support for the Hun regime’s stability, which has not received support from the Western capital due to its undemocratic tendencies. Therefore, amidst mounting pressure from the US, Cambodia’s earlier actions must be viewed through the lens of a small state trying to bolster its regime security by adopting bandwagoning with Beijing and rejecting hedging. However, since Hun Manet, the son of Hun Sen, took over as the Prime Minister, he has tried to diversify Cambodia’s foreign policy, reaching out to the US, Japan, South Korea, France, and Australia, realising the changing geopolitical trends in the Indo-Pacific region and reasserting Cambodia’s independent, rules-based and smart foreign policy. Against this backdrop, Cambodia is again opening doors to the US; recently, the US Secretary of Defence and the CIA director visited the state to discuss resuming bilateral defence cooperation, which seems to be a course correction on Washington’s part and Cambodia's return to hedging strategy. Cambodia’s adjustment is also a result of the US upgraded partnership with Vietnam and China’s increasing coercive actions in the South China Sea. Through these foreign policy modifications, Cambodia is also signalling to its neighbours, Vietnam and Thailand, that it is committed to strengthening relations and doesn't want to be a pawn in great power rivalry. All these actions are taken to maximise Cambodia's national interests. Despite the readjustments, cooperation with China will likely increase while simultaneously its diversifying foreign policy continues.

Conclusion

China's growing influence in Cambodia, driven by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has deepened bilateral ties. Substantial infrastructure investment, including dual-use projects like the Ream Naval base, serves both economic and strategic ends. While Cambodia benefits economically, concerns over debt and over-reliance on China persist. However, recent diplomatic approaches to Western powers signal a desire for a more balanced foreign policy. As Cambodia navigates this complex situation, balancing economic gains with strategic autonomy will be crucial.

Prithvi Gupta is a Junior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Abhishek Sharma is a Research Assistant at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV