The Indo-Pacific is an idea whose time has come. Recognising that the centre of gravity in Asia is shifting south and west, many governments have adopted the Indo-Pacific as a spatially-expanded conceptualisation of who and what constitutes the Asian region. The concept has a clear security logic: reflecting the strategic importance of sea lines of communication linking the Indian and Pacific oceans, and India’s demonstrable importance as a regional security actor.

However, the economic case for the Indo-Pacific is less developed. There is yet to emerge a critical mass of trade or investment ties linking South Asia to economies on the Pacific Rim, nor significant intergovernmental initiatives to build these ties. Tellingly, the most visible institutional manifestation of the Indo-Pacific — the “Quad” grouping of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States — is a maritime security-focused dialogue. Nor is India well-integrated into economic institutions. While it is a member of the East Asia Summit, the premier regional forum for strategic dialogue, it is not involved in the economically-focused Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC).

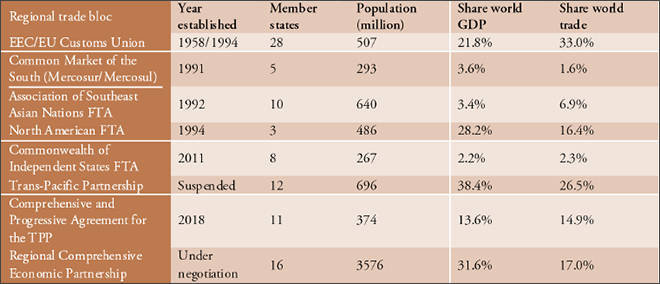

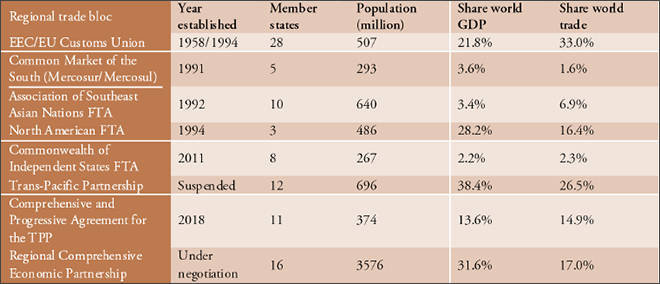

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) promises to change this. RCEP is one of several “mega-regional” free-trade agreements (FTAs) launched in recent years.<1> It seeks to create a sixteen-member trade architecture, comprising the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the six countries with which it has a plus-one FTA: Australia, China, India, Japan, Korea, and New Zealand. RCEP is systemically significant for the global trading system, accounting for almost half of the world’s population, over 30 percent of global GDP, and over a quarter of global exports.<2> In GDP and population terms, a concluded RCEP will constitute the world’s largest trading bloc (Table 1). Significantly, by including India, it is the first regional economic institution to have an Indo-Pacific geographic scope.

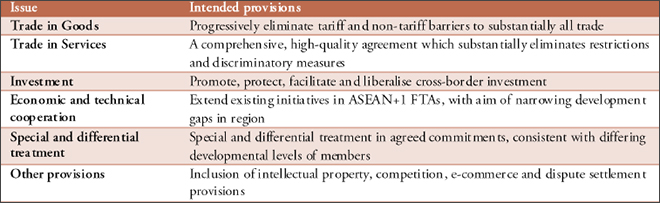

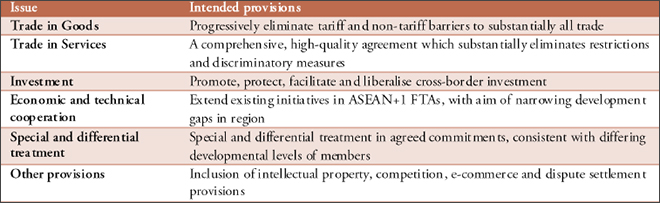

As per the “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership” of 2013, its principal purpose is to “achieve a modern, comprehensive, high-quality and mutually beneficial economic partnership agreement among the ASEAN Member States and ASEAN’s FTA Partners.”<3> Given the diversity of development levels within its membership, RCEP has focused on traditional trade reforms, such as tariff reduction and at-the-border measures. This is in contrast with the other mega-regional FTA in Asia — the recently-revived Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) — which includes a range of advanced trade-related regulatory measures across the investment and services domains. RCEP’s more modest ambitions in comparison to the TPP reflect its status as a multilateral FTA designed by, and to suit the needs of, developing economies in Asia.

At the regional level, RCEP’s developing country-focused model will likely become the template for the next phase of trade and investment liberalisation.

Notwithstanding its regulatory ambition, the successful conclusion of RCEP will establish the first genuinely Asian regional trade agreement since the ASEAN FTA of 1992, and the first Indo-Pacific economic institution of any kind. Amidst the turbulence confronting global trade politics and trading institutions, this will send a strong message that the region remains committed to a rules-based approach to trade and investment liberalisation. It will help knit India into the regional trading system, which was a critical foundation for the Asian economic miracle that began in the mid-1980s. It will also help ensure that the Indo-Pacific is a “complete” regional concept, containing both security and economic architectures. RCEP will thus be a landmark achievement in the maturation of the Indo-Pacific regional concept.

An Asian mega-regional trade agreement

RCEP was launched on the margins of the 2012 East Asia Summit. It emerged from a series of earlier proposals for a region-wide FTA and, along with the TPP, was positioned as a “pathway” to APEC’s longer-term goal of creating the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP).<4> But, unlike the TPP, RCEP offered a far more regionally-focussed approach to membership. It did not include the extra-regional APEC members of North and South America, but compensated with the inclusion of all Asian economies, including China, Korea, India, Japan, and the full ASEAN bloc. This Asia-focused approach to membership is reflected in its goals. RCEP embodies a desire to achieve a regional trade architecture that would ensure all members are “provided with the opportunities to fully participate in and benefit from deeper economic integration and cooperation.”<5>

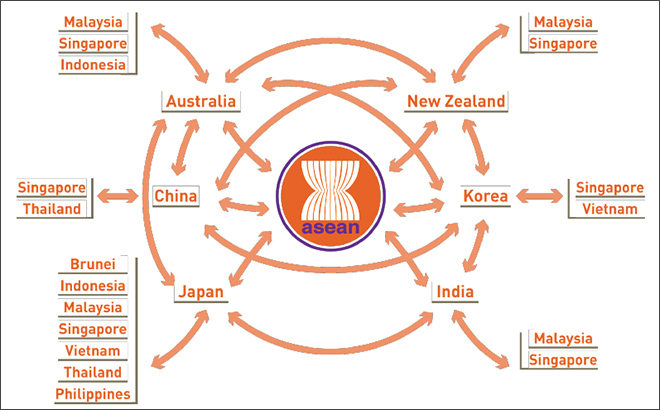

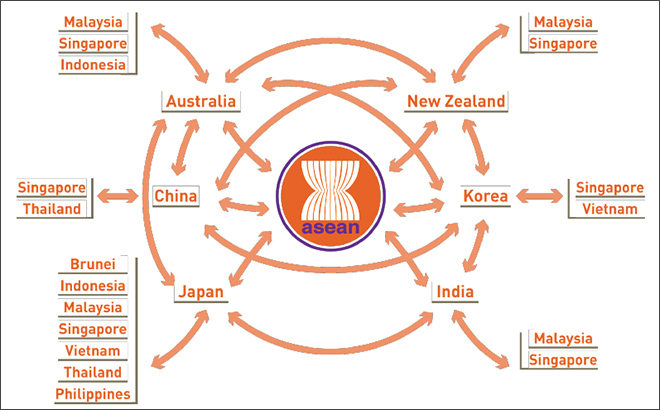

RCEP is frequently compared with the TPP, the other mega-regional trade agreement in Asia. Both share the common goal of offering a multilateral approach to trade liberalisation. Since the turn of the century, the number of bilateral FTAs within the Asia-Pacific has increased from four to fifty-two.<6> However, there are major differences across these bilateral agreements in terms of their tariff reduction commitments, investment protections, and other regulatory provisions. This has led to the so-called “noodle bowl” problem, where the regional trade system has fragmented into multiple, overlapping, and inconsistent bilateral FTAs. Bilateral FTAs also tend to favour the interests of larger developed economies, who have the heft to extract better deals in bilateral negotiations than smaller developing counterparts. In architectural terms, both the TPP and RCEP promise a return to trade multilateralism — albeit at the regional rather than global level.

Institutionally, RCEP offers an ASEAN-focused rather than APEC-based approach to trade multilateralism. RCEP formally endorses the principal of “ASEAN Centrality,”<7> and uses a closed membership model limited only to ASEAN and its current FTA partners. However, in economic terms ASEAN is a comparatively small party, accounting for only 11 percent of RCEP’s combined GDP. China (47 percent) and Japan (21 percent) are the economic heavyweights of the bloc. While India currently holds a modest share (9 percent), its high-speed growth trajectory promises to make it a core player in future years. One of the key challenges for RCEP negotiators is therefore to strike a balance between its ASEAN-centred institutional form and its China/Japan/India-dominated economic geography.

Indeed, this has proven to be a major challenge during negotiations over the last five years. As of December 2018, twenty-four rounds of negotiations have been conducted, supported by six intersessional Ministerial meetings, with Leaders’ discussions held on the margins of ASEAN summits. Only seven regulatory chapters have been concluded, and there remains several gaps to be closed in market access negotiations.<8> Aspirational deadlines for RCEP’s conclusion have consistently been missed. In its “Guiding Principles” statement, the end of 2015 was benchmarked as the deadline for negotiations. In November 2015, the deadline was moved to 2016, and in late 2016 Leaders called for a “swift conclusion” to RCEP.<9> At the second RCEP Summit in November 2018, the target was again moved to 2019.

These delays are in part explained by the considerable diversity within the RCEP bloc. Its members include some of the most advanced members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, alongside several lesser-developed economies, who naturally have major differences between their economic interests and capacity for trade reform. RCEP negotiations have also given prominence to China and India, two countries which have historically not performed leadership functions within regional economic organisations. They also have divergent views on which elements should be prioritised, with China favouring a strong outcome for trade in goods while India pushes for increased services liberalisation.<10> The scope and implementation timetable for bilateral market access exchanges between China and India has turned out to be one of the most challenging elements of the negotiations.<11>

The travails affecting the TPP have further increased RCEP’s importance for the regional trade architecture. When TPP negotiations completed first in 2015, many analysts expected it to become the principal vehicle for multilateralising the regional trade architecture. These expectations were decidedly quashed with the election of Donald Trump in late 2016, who campaigned extensively against the TPP. President Trump withdrew the US from the agreement with his first executive order in January 2017.<12> In the following months, the eleven remaining TPP members scrambled to find a way to salvage the agreement. Led by Japan, these efforts bore fruit in March 2018 with the signing of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for TPP (CPTPP).<13> While the CPTPP retains most of the original agreement’s advanced rule-making provisions (suspending only a range of intellectual property measures), the absence of the US has reduced the TPP bloc to less than half its original size (Table 1).

As a consequence, RCEP remains a leading prospect for driving a new phase of economic liberalisation in Asia. Its membership is genuinely inclusive of all Asian countries, and is of a sufficient size to claim systemic importance in the global trade system. A concluded RCEP will turn a page on two decades of bilateral trade deals in the region, returning the Asian region to an inclusive and member-driven multilateral architecture. The unresolved challenge for RCEP negotiators is being able to conclude an agreement that not only strategically integrates the economic forces of the region, but also drives economic development.

A developing-country calibrated trade model

RCEP offers a more “traditional” model for trade liberalisation than the TPP. Its objectives are principally focused on liberalising barriers to goods and services trade at the border, involving the elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers (Table 2). The broader range of regulatory provisions in the TPP — across issues as diverse as e-commerce, intellectual property, environment, labour, and financial services — are not core elements of the RCEP negotiating agenda. While RCEP will include an investment framework, this is intended primarily to facilitate cross-border capital flows, not harmonise national investment regimes. While the TPP is considered a “WTO-Plus” type of agreement, RCEP instead aims for a “WTO-consistent” approach.

RCEP’s WTO-consistent approach reflects the need to find a common ground that meet the needs of its diverse membership. This is particularly true for India and the Cambodia-Myanmar-Laos-Vietnam, or CMLV group, which have approached negotiations at an earlier stage of development than either other ASEAN or the more developed country members. Trade liberalisation is especially challenging for these economies. Tariffs often constitute a significant component of state budgets, requiring complex taxation reforms to compensate for lost revenues. Agricultural liberalisation also constrains several of the policy tools — including price controls and import quotas — which have historically been used to stabilise highly-volatile agricultural markets and ensure food security. Competition from manufacturing imports will also impose structural adjustment costs for certain sectors, even if the aggregate gains for the economy as a whole will be positive.

Table 1: Comparison of major regional trade agreements, 2016

Source: Authors’ calculations from WTO Regional Trade Agreements Database, UNCTAD Stat Database and United Nations Population Division Standard Projections

Source: Authors’ calculations from WTO Regional Trade Agreements Database, UNCTAD Stat Database and United Nations Population Division Standard Projections

RCEP’s modest ambitions are an explicit attempt to address these challenges for developing economies. By avoiding the more complex and costly WTO-Plus provisions in favour of a focus on conventional liberalisation measures, it poses lower reform costs for developing country members. While reform costs will certainly have to be carefully managed, their quantum is far easier to achieve than for a WTO-Plus agreement like the TPP. Another part of RCEP’s equitable development objectives are the special and differential treatment provisions for less-developed members, and the inclusion of economic and technical cooperation partnerships. The latter is especially important, and will offer assistance to improve the technical and bureaucratic capacity of smaller parties.

Even a modest RCEP agreement will be a landmark achievement. It will help alleviate the noodle bowl of bilateral trade deals, which, as Figure 2 illustrates, has become a challenge in organising regional trade arrangements. There are presently twenty-eight bilateral FTAs between the RCEP negotiating parties, in addition to the ASEAN FTA and its six plus-one extensions. Each contains radically different provisions, with varying standards on tariff reduction, rules-of-origin, customs procedures, dispute settlement, and investment and services regulations. Compliance with these complex rules impose significant transaction costs for businesses, which are especially pronounced when regional value chains several distinct markets. While RCEP will not eliminate existing FTAs, it will provide a single, consistent, and cohesive set of trade rules above them to mitigate the negative effects of the noodle bowl.

Significantly, RCEP will for the first time include India in a major piece of the regional economic architecture. India’s economy is not yet substantially connected into East and Southeast Asia: only one quarter of India’s two-way trade is with Asia (compared with approximately half of other Asian countries’ trade), and there are substantially lower levels of two-way investment between India and the rest of Asia.<14> Part of this lack of economic integration is due to India’s ongoing economic liberalisation process, as well as the greater geographical, infrastructural, and socio-political distance between it and many Asian countries. However, it also reflects India’s absence from the regional economic architecture. It is not a member of APEC or the ASEAN+3 (two key dialogue platforms for economic cooperation), and presently only has RCEP country FTAs with Malaysia and Singapore.<15> RCEP will provide an institutional foundation for closing these economic gaps, which major opportunities for both India and its regional partners to develop mutually-beneficial trade and investment ties.

Table 2: Key provisions in RCEP negotiations

Source: “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”

Source: “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”

There are also a number of other RCEP economies who do not have bilateral FTAs with one another, including China-Japan, China-India, India-Indonesia, Japan-Korea, and Australia-India. For some, bilateral trade negotiations are ongoing, while others are unlikely to be launched. RCEP offers the clearest path forward to establish a new network of trade arrangements to increase economic connections between these countries. For example, when establishing a Comprehensive Strategy Partnership in May 2018, the leaders of Indonesia and India prioritised RCEP as a key driver in their new economic partnership.<16> For Australia and India, who have long been unable to reach agreement on a bilateral FTA, RCEP offers a more practical avenue to realise stronger trade relations.<17>

RCEP and the emerging Indo-Pacific concept

RCEP would be the first regional economic institution with an Indo-Pacific geographic scope. The Indo-Pacific is a new geographic conceptualisation, extending the prior “Asia-Pacific” concept south and west to include India and countries along the Indian Ocean rim. Since the early 2010s, this concept has been adopted by many governments as a frame of reference for their regional and foreign policies.<18> This has occurred to recognise the rise of India as a major power, and appropriately address the growing economic and strategic linkages ning the Indian and Pacific oceans. Yet, the Indo-Pacific remains an embryonic concept, and intergovernmental institutions with an Indo-Pacific scope are yet to be formed. India’s involvement means the completion of RCEP will advance the realisation of an Indo-Pacific economic framework.

The revival of the CPTPP in early 2018 means that RCEP is not the only mega-regional trade agreement in Asia. Nonetheless, its conclusion will have lasting impacts upon both the regional and global trading architectures. A concluded RCEP will constitute the world’s largest trade bloc by both GDP and population, and be the second largest (behind the EU) in terms of share of world trade (Table 1). Moreover, the growth prospects of many RCEP parties — including China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam — are on a higher trajectory than the global average. Of the twenty economies predicted to be the world’s largest in 2050, seven are RCEP countries.<19> This will support the group’s growing stature and significance, and over time it is likely to grow faster than any other regional agreement.

Figure 2: Bilateral FTAs within RCEP bloc, 2018

Source: Asian Development Bank ARIC FTAs Database

Source: Asian Development Bank ARIC FTAs Database

The implications of RCEP’s current and expected future size for the regional and global trading architectures are significant. At the regional level, its developing country-focused model will likely become the template for the next phase of trade and investment liberalisation. Much larger than the CPTPP, and claiming all regional governments as members, its completion will make a “WTO-consistent” approach the leading model for regional trade law. At the global level, RCEP’s standards will also have a significant impact on ongoing efforts for new WTO agreements, subsequent to the breakdown of the Doha Round negotiations.

However, RCEP’s systemic impacts will depend on the nature of its final membership model. During the negotiating phase, it has used a closed model, including only the ASEAN and the six plus-one FTA partners in talks. While providing a degree of negotiating stability, this prohibits the addition of new members. In the “Guiding Principles,” it is stipulated RCEP will have an “open accession clause” for new partners once the agreement is completed and has entered into force. Whether and how RCEP includes such an open accession mechanism remains to be determined, and will ultimately bear upon the extent to which it advances regional integration. An accession mechanism which imposes high barriers to new members, and/or sets geographic constraints on the countries which may join would limit RCEP’s capacity to function as a nucleus from which further trade liberalisation can grow.

Geopolitical implications

As per its “Joint Declaration” and “Guiding Principles,” RCEP reaffirms ASEAN centrality in regional processes. While ASEAN lies at the heart of the Indo-Pacific region, and some member states have individually begun using the Indo-Pacific concept, ASEAN as a grouping is yet to formally adopt the construct. A concluded RCEP would likely advance its adoption in Southeast Asia by creating an Indo-Pacific institution in which ASEAN’s central position is secured. It would also be a victory for ASEAN consensus on trade and investment processes at the same time that the ASEAN Economic Community is seeking to grow in stature and institutional prowess. RCEP will support ASEAN remaining the strategic convenor of the broader region’s processes, particularly in economic integration matters.

With India becoming a great power both economically and strategically, it is now pursuing closer economic relations with its neighbours.<20> As detailed above, India is less economically integrated with the region than most other Asian economies. RCEP thus provides India with an eastern economic bridge into such arrangements, and will advance India’s economic integration in the Indo-Pacific region. The momentum from a concluded RCEP could also support India’s accession into APEC. If RCEP becomes the model for the realisation for APEC’s aspiration for FTAAP, India would be locked into this core APEC initiative. As India acts east by seeking economic and strategic interconnectedness in Northeast and Southeast Asia, RCEP will provide opportunities to develop the required trade and investment linkages.

With the US not a party to RCEP, its conclusion willenhance China’s rise as a multilateral leader. While an ASEAN-centred initiative, China is the principal economy of RCEP and therefore a lynchpin negotiator. Even though RCEP is not a rule-creating agreement of CPTPP standard, it nonetheless has provided China a platform to burnish its regional leadership credentials.<21> Occurring at a time when the international rules-based order is under strain, it allows China to position itself as an institution-builder that contributes to the supply of rule-making bodies. Additionally, a concluded RCEP (along with the CPTPP) will create another institution for Indo-Pacific regional integration to which the US is not a party. With President Trump skipping both the APEC and East Asia Summits in 2018,<22> this will contribute to a shift towards less US engagement in the multilateral architecture of the Indo-Pacific.

With the revival of the CPTPP, countries in the region will face strategic choices with respect to which agreement(s) they seek membership. RCEP offers a politically-easier prospect for regional trade multilateralism, given its Asian membership model and developing country-friendly standards. It remains to be seen whether and when RCEP can be completed, and if so, how its declared ambitions will be realised. But given its size and geographical scope, a concluded RCEP is the most likely template for creating the first piece of Indo-Pacific economic architecture.

This essay originally appeared in The Raisina Files

Endnotes

<1> Jeffrey Wilson, “Mega-regional Trade Deals in the Asia-Pacific: Choosing between the TPP and RCEP?,” Journal of Contemporary Asia 45, no. 2 (2015): 345-353.

<2> “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government.

<3> “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”.

<4> “Annex A: Lima Declaration on FTAAP”, Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation.

<5> “Joint Declaration by Leaders on the Launch of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”.

<6> Jeffrey Wilson, “The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership: An Indo-Pacific approach to the regional trade architecture?,” Indo-Pacific Insights Series, Perth USAsia Centre, January 2017.

<7> See note 5.

<8> “Joint Leaders’ Statement on the RCEP Negotiations – 14 November 2018”.

<9> “ASEAN’s nature and ‘endless’ RCEP negotiations,” The Jakarta Post, September 1, 2018.

<10> Melissa Cyrill, “The RCEP Trade Deal and Why its Success Matters to China”, China Briefing, September 6, 2018.

<11> “RCEP Members Agree to Liberalise Services Market, Other Concessions for India”, India Briefing, September 5, 2018.

<12> President Donald J. Trump, Presidential Memorandum Regarding Withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Negotiations and Agreement, 23 January 2017.

<13> Jeffrey Wilson and Hugo Seymour, “Expanding the TPP: Options, prospects and implications for the Indo-Pacific,” Economics of the Indo-Pacific series, Perth USAsia Centre, July 20, 2018.

<14> Jeffrey Wilson, “Investing in the Economic Architecture of the Indo-Pacific,” Indo-Pacific Insights series, Perth USAsia Centre, August 2017.

<15> India also signed a trade agreement with Thailand in 2004, but its limited sectoral coverage means it is presently registered with the WTO as a “partial scope agreement” rather than economy-wide FTA.

<16> “India, RI vow to widen economic ties,” The Jakarta Post, May 31, 2018.

<17> Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, An India Economic Strategy to 2030: Navigating from Potential to Delivery. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 2018.

<18> Jeffrey Wilson, “A New Region? Building partnerships for cooperative institutions in the Indo-Pacific”, Report from the Perth USAsia Centre Australia-US Indo-Pacific Strategy Conference, April 13, 2018.

<19> PwC, The World in 2050.

<20> Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue, delivered at Shangri La Dialogue, Singapore, June 1, 2018.

<21> “APEC Summit: Xi Jinping pledges economic openness as leaders seek free trade options,” ABC, November 20, 2016.

<22> “Trump Is Skipping All of These Asia Summits,” Bloomberg, November 11, 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: Authors’ calculations from WTO Regional Trade Agreements Database, UNCTAD Stat Database and United Nations Population Division Standard Projections

Source: Authors’ calculations from WTO Regional Trade Agreements Database, UNCTAD Stat Database and United Nations Population Division Standard Projections Source: “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership”

Source: “Guiding Principles and Objectives for Negotiating the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership” Source: Asian Development Bank ARIC FTAs Database

Source: Asian Development Bank ARIC FTAs Database PREV

PREV