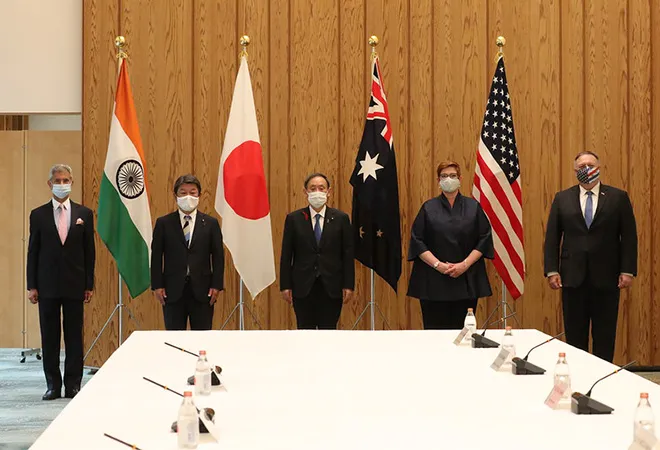

Despite all the hype, the Quad ministerial meeting in Tokyo turned out to be predictable and fairly routine. The meeting, hosted by the Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne and the External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, was significant since it was the first “stand-alone” one, as compared to the first which was held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly session last year.

The meet has come at a time when the Indo-Pacific region, along with the rest of the world, has been reeling from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Simultaneously, China’s aggressiveness has been manifested in the straits of Taiwan, South China Sea, eastern Ladakh and, of course, Hong Kong. However, expectations that the meeting could see moves towards the “institutionalisation” of the Quad have been belied.

As expected most of the sound and fury were generated by the

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo who called for the democracies to collaborate “to protect our people and partners from the Communist Party of China’s exploitation, corruption and coercion.” With reference to this, he spoke of the Chinese activities in the East China Sea, the Mekong, the Himalayas, and the Taiwan Straits.

Expectations that the meeting could see moves towards the “institutionalisation” of the Quad have been belied.

The other ministers present were more restrained and avoided naming China directly. In his opening remarks, the Indian

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar was content to call for “like minded countries to coordinate responses,” this notwithstanding the difficulties India is in with China on its borders. He went on to add that “we remain committed to upholding the rules-based international order, underpinned by the rule of law, transparency, freedom of navigation in the international sea, respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty and peaceful resolution of disputes.” The formulation was fairly standard, but for the pointed reference to the “respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty,” though there was no reference to China in his public remarks.

The minister was clear, too, that India’s objective remained in “advancing the security and economic interests of all countries having legitimate and vital interests in the region.” It should be clear that while India has an Indo-Pacific policy

, articulated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June 2018, it is not part of the grouping that places the qualifier “Fee and Open” in front of the “Indo-Pacific.”

In that sense New Delhi continues to

belie expectations that it would become as active a votary of the Quad as Japan, US and Australia after its Himalayan standoff this summer. The key marker of New Delhi’s attitude though is likely to be India’s invitation or the lack of it, to Australia, to participate in the annual Malabar naval exercises that are scheduled to be held later this year. While sufficient hints are there that Canberra will be invited, as of now no formal invitation has been sent.

The key marker of New Delhi’s attitude though is likely to be India’s invitation or the lack of it, to Australia, to participate in the annual Malabar naval exercises that are scheduled to be held later this year.

The Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne too was careful not to name China because

she insisted that the Quad has a positive agenda based on the shared interests of democratic countries. These interests include an upholding of individual rights, the importance of settling disputes under international law. At present, however, the focus was on recovery from Covid-19.

She spoke of the longer range cooperation in areas including maritime security, cyber affairs, technology, humanitarian aid and disaster relief and referred obliquely to the ongoing efforts to move supply chains away from China and to compete with Beijing on developing “quality infrastructure.”

A press release issued by the Japanese foreign ministry after the meeting and the ministerial dinner noted that the ministers had “exchanged views on the regional situation in North Korea, East China Sea and South China Sea.” No reference was made to China or the eastern Ladakh standoff. The release spoke of the need to broaden the cooperation with more countries, especially that of the ASEAN.

In a sense, the elephant in the room is the ASEAN. Many of the issues that the Quad is speaking about, the South China Sea and the Mekong, relate to ASEAN. However, as of now there are no signs that the ASEAN is willing to take a united stand on them. It would be difficult for the Quad to execute any effective policy minus the cooperation from the ASEAN countries. Payne did talk in her remarks of ASEAN centrality and the need for ASEAN-led architecture for the success of the Indo-Pacific agenda. Likewise, the Japanese press release noted that the ministers had “reaffirmed their strong support for ASEAN’s unity and centrality.” But slowly and steadily, the security mechanisms like East Asia Summit, ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) and the ASEAN Defence Ministers Meeting Plus, where China is also a member, are being brushed aside by the Quad, which is working along an entirely different agenda.

It would be difficult for the Quad to execute any effective policy minus the cooperation from the ASEAN countries.

The June 2019 ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific self-consciously steered itself away from creating any new mechanism or replacing existing ones. Aimed at underscoring the centrality of the ASEAN to any Indo-Pacific strategy, it declared its goal as one of further strengthening and optimisation of ASEAN-led mechanisms like the ARF, ADMM Plus and so on.

But as Prof. Swaran Singh has noted, there has been a clear drift away from the ASEAN occupying the driving seat on the issue of a regional security architecture. He points out that “the centrality of the ASEAN was premised on never hurting the core interests of major powers” but that this has been “compromised with China emerging as a global power with system shaping capabilities.”

Not surprisingly, given its foreign policy activism, Beijing has now become much more critical of the Quad than it has been in the recent past. Last month, China’s vice foreign minister and the previous ambassador to India

Luo Zhaoui gave a speech in which he squared the UNCLOS circle and insisted that China had upheld it in the South China Sea. He accused the US of creating the Quad, “an anti-China frontline, also known as the mini-NATO.”

The focus of the Quad is largely on the western Pacific Ocean. However, countries like India, and now France and Germany, see the need for a larger Indo-Pacific strategy that takes into account the entire Indian Ocean as well as the Pacific. In his speech to the Shangri-La Dialogue,

Prime Minister Narendra Modi had emphasised that in the Indian vision, the Indo-Pacific extended “from the shores of Africa to that of the Americas” where India would promote a “democratic and rules based order, in which all nations, small and large thrive.”

India has huge and complex interests in the western Indian Ocean where there is a huge opportunity to step up cooperation with the EU.

Countries like France and Germany have more recently begun to speak of the need for an Indo-Pacific strategy whose scope goes beyond issues of security. In this vision, there is a certain duality about the Indo-Pacific. It is a region of economic opportunity, as well as one of problems. The goal of the partnership of democratic nations is to enhance the former and deal effectively with the latter. India partners with the US, Japan and Australia in the western Pacific and eastern Indian Ocean region. But it has huge and complex interests in the western Indian Ocean where there is a huge opportunity to step up cooperation with the EU.

The scope of cooperation in the Indo-Pacific ranges from security, ecology, trade, disaster relief, development and so on. There is a need to build a coalition of like-minded states to encourage an observance of the rule of international law, peaceful settlement of disputes, tackling climate change or trade and industrial policies. But the scope of the policy needs to cover the entire Indo-Pacific, not just one part of it.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Despite all the hype, the Quad ministerial meeting in Tokyo turned out to be predictable and fairly routine. The meeting, hosted by the Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne and the External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, was significant since it was the first “stand-alone” one, as compared to the first which was held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly session last year.

The meet has come at a time when the Indo-Pacific region, along with the rest of the world, has been reeling from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Simultaneously, China’s aggressiveness has been manifested in the straits of Taiwan, South China Sea, eastern Ladakh and, of course, Hong Kong. However, expectations that the meeting could see moves towards the “institutionalisation” of the Quad have been belied.

As expected most of the sound and fury were generated by the

Despite all the hype, the Quad ministerial meeting in Tokyo turned out to be predictable and fairly routine. The meeting, hosted by the Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne and the External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar, was significant since it was the first “stand-alone” one, as compared to the first which was held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly session last year.

The meet has come at a time when the Indo-Pacific region, along with the rest of the world, has been reeling from the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Simultaneously, China’s aggressiveness has been manifested in the straits of Taiwan, South China Sea, eastern Ladakh and, of course, Hong Kong. However, expectations that the meeting could see moves towards the “institutionalisation” of the Quad have been belied.

As expected most of the sound and fury were generated by the  PREV

PREV