-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

LDCs in Africa struggle with high-risk loans for climate adaptation. Debt swaps, green bonds, and sustainability-linked bonds could provide needed funding

Image Source: Getty

Despite being at high risk due to climate change and being the lowest historical emitters, the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), primarily concentrated in Africa, are paying a high interest rate of 25 percent on loans from developed economies, development finance institutions, multilateral development banks (MDBs). LDCs need US$ 40 million per country, per year for adaptation finance to effectively deal with the climate crisis. According to the Global Environmental Fund (GEF), LDCs currently have a shortfall of US$ 20 million per country, per year. The only adaptation fund for LDCs is the Least Developing Countries Fund (LCDF), which extends US$ 1.7 billion in grants from the World Bank Group. However, funding from LCDF is directed towards mitigation rather than adaptation projects. The lack of adaptation finance, combined with high dependency on the international finance community through high-interest rate loans that are not suited to meet their domestic climate resilient infrastructure requirements, is affecting the climate readiness of LDCs.

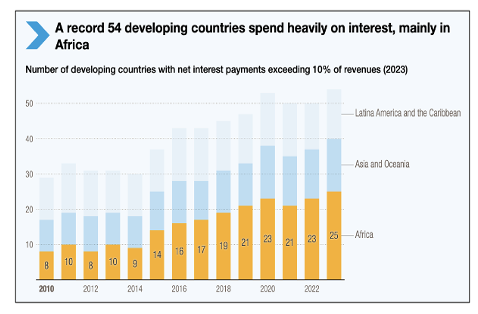

Figure 1: Interest rate paid by African Countries

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, 2024

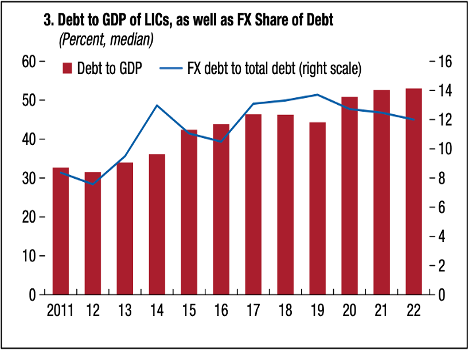

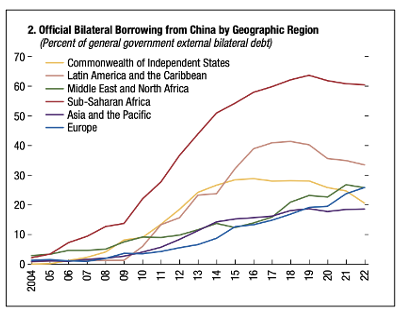

LDCs have a high debt-to-GDP ratio. As per the Least Developed Countries Report, 2023, the GDP-to-debt ratio in LDCs was 55.4 percent in 2022. LDCs borrow money to meet their citizens' daily livelihood needs. This high GDP-to-debt ratio has resulted in slow economic growth, low domestic revenue, and minimal climate-resilient infrastructure. In addition to paying high capital costs, most LDCs in Sub-Saharan Africa have been subjected to China’s debt trap diplomacy. Almost 60 percent of external government debt in Sub-Saharan Africa is owed to China, as shown in Figure 3. Governments in LDCs have been unable to prioritise strong macroeconomic policies to increase governmental revenue price stability and lower the cost of borrowing on the external and domestic front.

Figure 2: Debt to GDP of LDCs and Debt in Foreign Exchange

Source: IMF, Global Financial Stability Report (2024)

Figure 3: Debt to GDP of LDCs and Debt in Foreign Exchange

Source: Fiscal Monitor (2024)

Climate change disproportionately affects LDCs, exacerbating poverty, food insecurity, and environmental degradation. If the global community fails to address the climate crisis sincerely, LDCs will face severe repercussions leading to economic instability, widespread migration, and conflict, affecting them domestically, in their neighbourhoods, and across continents. LDCs must be economically empowered to take charge of their developmental needs and advance climate financing to avoid the repercussions on environmental and socio-economic fronts. Regional MDBs like the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Asian Infrastructure Investments Bank (AIIB) have not yet focused on investment in LDCs adaptation infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa apart from Bangladesh and a few Pacific Islands.

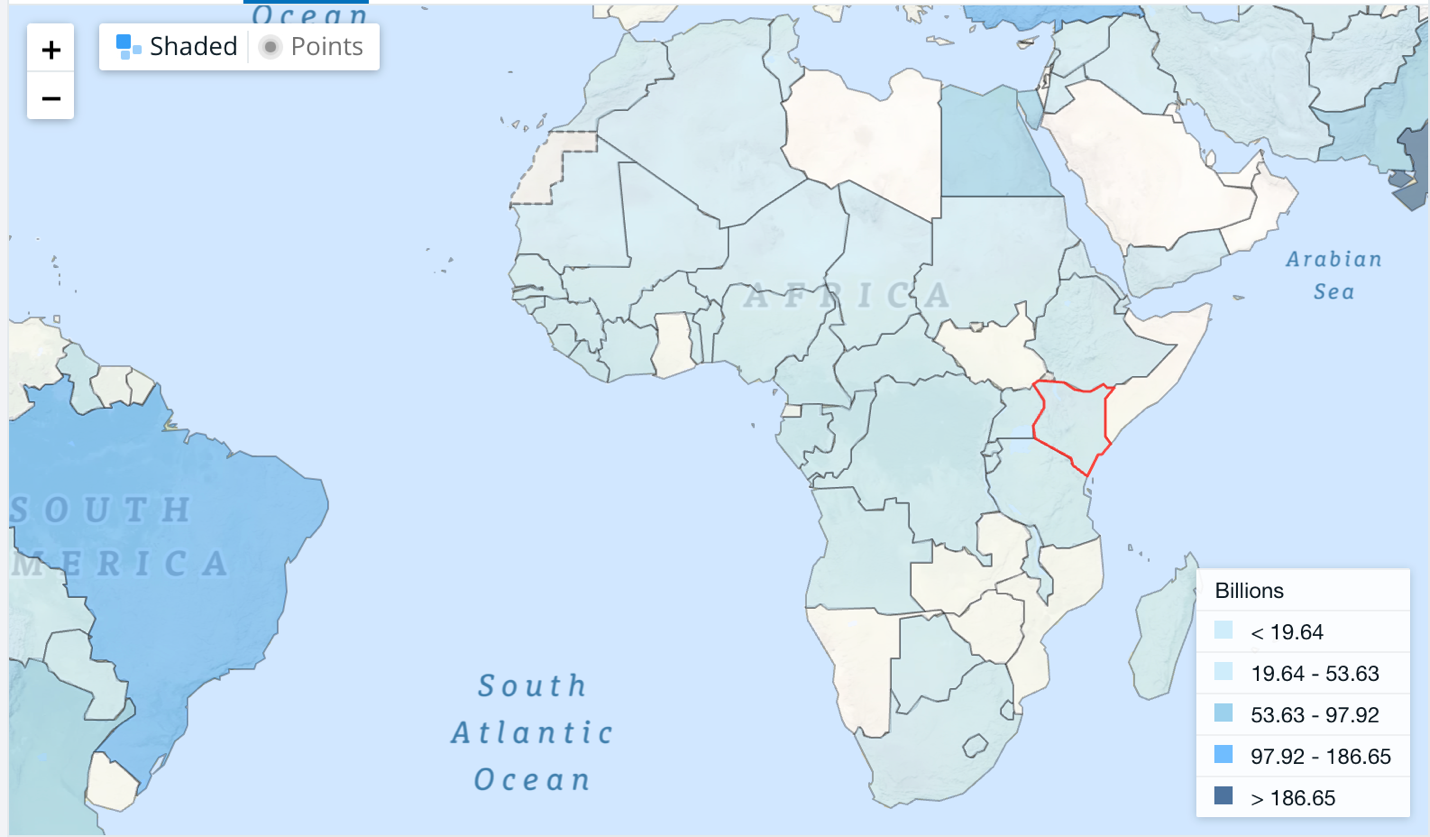

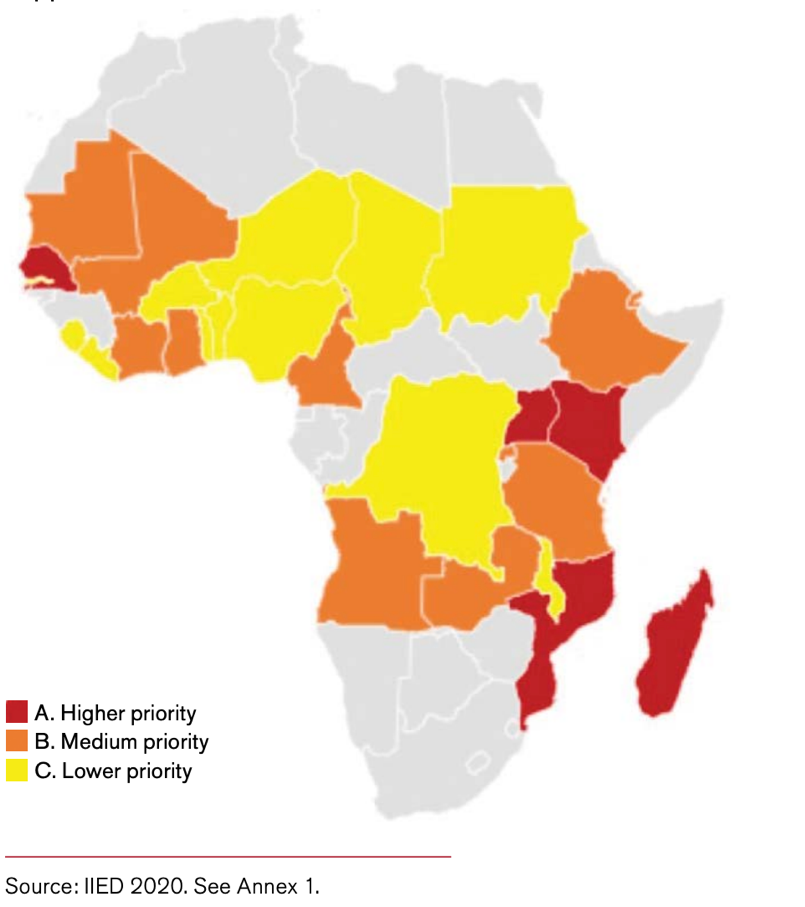

LDCs face a triple crisis of climate change, debt distress, and nature loss. They are spending their tax revenue on interest repayment, leaving no funds for adaptation projects, which reduces their capacity to deal with the climate crisis. One suitable mechanism is ‘debt for nature swaps’ in the United Nations Development Programme literature. The ‘swaps’ are suitable for countries with high climate risk and debt stress. As seen in Figure 5, African countries have high debt and a high risk of climate crisis. Debt for nature swaps is a suitable option for high and medium-priority LDCs, as seen in Figure 6. These economies are in social and fiscal distress and can create additional revenues for countries with high biodiversity and natural resources. The debt for nature swaps could prove to be a powerful instrument for afforestation as they will parallelly focus on debt reduction while building climate-resilient infrastructure.

Figure 4: Value of External Debt in Africa in 2022

Figure 5: Climate risk category of African Countries, 2021

The example of Ecuador demonstrates the working of this instrument. In 2023, it signed the most significant debt-for-nature swap with support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the US Development Finance Corporation (DFC). The country’s debt purchase from IDB and DFC saves the country US$ 1.126 billion, and savings are already directed towards marine conservation efforts. IDB guaranteed US$ 85 million in this swap for marine project operations, and DFC bought political-risk insurance for US$ 656 million. Ecuador’s swap is an example of how countries with high natural and political risks can adopt a multistakeholder approach to be climate resilient.

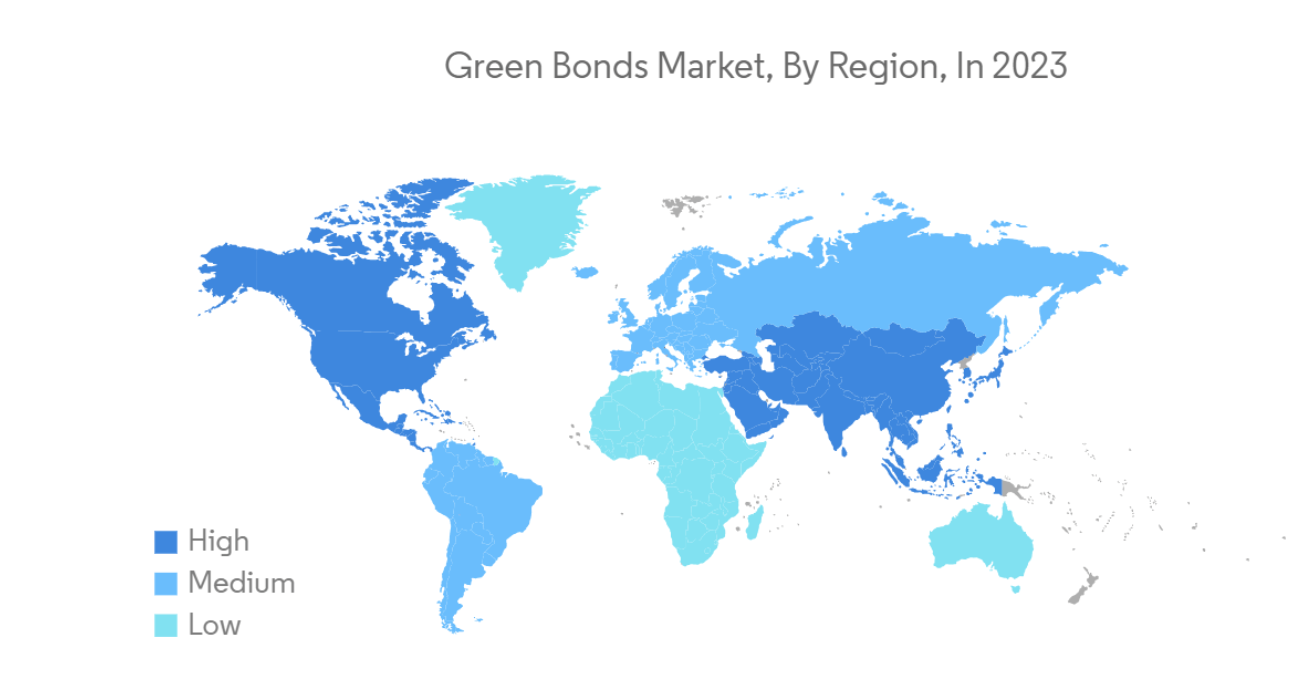

Figure 6: Issue of Green Bond by Region

LDCs have weak financial institutions, which exposes them to development challenges like restricted access to capital, underdeveloped infrastructure, reduced foreign investment, and lack of innovation. Figure 7 shows green bonds are widely issued in the US and Europe to raise large-scale capital to finance climate-related projects. African LDCs are unable to avail themselves of the benefits of green bonds due to weak financial institutions. As a result, private and international organisations are not investing in the African green bond market and are deprived of the region’s inherent resource reservoir. Green bonds bring in the much-needed capital for LDCs to combat climate change and advance sustainable development growth through environmental sustainability. Secondly, green bonds can be issued at lower interest rates, which makes them an attractive option for LDCs as it reduces total borrowing costs. LDCs with comparatively low debt-to-GDP ratios can effectively utilise proceeds from green bonds to transition away from fossil fuels towards clean energy and climate-smart agriculture.

Egypt’s example explains how Green Bonds can successfully bridge the climate finance deficit. In 2022, it became the first country in North Africa to issue green bonds with a target of US$ 500 million but, in turn, received US$ 3.7 billion with a lower coupon rate (annual interest rate paid by the issuer) of 5.25 percent. The success of the bond mainly goes to Egypt’s renewable energy initiatives along with urban development projects like monorail and water irrigation. The bond helped Egypt diversify its investor base and reduce its debt. Egypt’s model can be an example of climate commitment by leveraging a country's natural resources to bring monetary benefits to the economy while addressing climate change effectively.

SLBs are the best fit for LDCs with diverse climate infrastructure requirements like energy social projects. Bond proceeds can be used for any project as per the issuer's wish. The funding must flow into capacity building and operational efficiency for LDCs’ projects, which can be measured through quantifiable key performance indicators (KPIs). As of 2021, 60 percent of SLB proceeds were issued for energy projects, while the remainder of the funding is utilised for social projects such as education, gender diversity, etc.

Funding through SLBs will play a crucial role in advancing SDG goals in LDCs due to less operational cost and the increased role of the government as a local guarantor and project developer.

In SLBs, government officials can receive capacity-building training from empanelled entities deployed by MDBs/DFIs to enhance operational and administrative efficiency on a monthly and quarterly basis. SLBs projects can also help advance banking facilities, local businesses, and consumer products. Funding through SLBs will play a crucial role in advancing SDG goals in LDCs due to less operational cost and the increased role of the government as a local guarantor and project developer.

Rwanda is one such country which has successfully experimented with SLBs. In 2023, it issued Eastern Africa’s first SLB, raising US$ 24 million of a planned US$ 120 million—the Development Bank of Rwanda—Banque Rwandaise de Développement (BRD)—initiative, with the support of the World Bank. The SLB was a credit enhancement mechanism, including a US$ 10 million escrow account (which allows two or more parties to make a transaction) to reduce investment risks. This bond issuance focused on enhancing environmental, sustainable governance (ESG) practices, funding women-led projects, and financing affordable housing. The SLB was oversubscribed, showcasing investor confidence and allowing BRD to offer lower interest rates. This success helped Rwanda diversify its funding sources, strengthen its domestic capital market, and reduce borrowing costs. Rwanda’s innovative approach is a model for other low-income countries to attract private capital, support sustainable development, and effectively address climate and social challenges.

Countries in the Global South should be at the forefront of solving climate challenges faced by LDCs. The examples of Ecuador, Egypt, and Rwanda, although they differ in geographies and have distinct environments, none of these countries have similar climate adaptation needs. Yet, they’ve availed financial mechanisms that help them adapt to climate change. BRICS economies, willing to provide technical and financial solutions to the world, are well-placed to encourage South-South cooperation by providing low-cost capital for climate adaptation. Regional developmental banks, such as BRICS, AIIB, or others like ADB and AfDB, could actively provide capital to LDCs. An integrated financial management system should be developed so LDCs can systematically monitor and evaluate allocated capital. Bank transactions for loan repayment can be completed in the economy's local currency to reduce the fiscal distress for LDC, allowing them to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio and focus on climate adaptation projects.

Amruta Veer is an Intern at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.