The past few decades have witnessed a gradual change in the purpose and nature of international development aid and assistance. Unlike in 1970s when the main purpose of aid was to solely foster economic growth, the contemporary polysemous notion of aid aims to accommodate several aspects of human well-being as enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the United Nations. The estimated ‘price tag’ for the realisation of these SDGs by 2030 would necessitate the mobilisation of US $2.5 trillion per year through Official Development Assistance (ODA) and private flows. On the other hand, the contending narratives of reducing ‘Aid Dependency’ in the Global South prompts us to evaluate the most fundamental question, ‘Is Development Aid still relevant?’ Thus, an evaluation of aid relevance becomes imperative on four accounts—aid effectiveness in terms of propelling tangible developmental outcomes, emergence of new donors in the Global South, composition of international capital flows, and change in the nature of aid from an economic to a political and security agenda.

An evaluation of the key debates in the international aid landscape

Major shifts in paradigms influence our perspective on development aid and determine its relevance. Tracing the historical evolution of aid suggests that till 1970s, the main purpose of aid was to fill resource and financial gaps and improve infrastructure to foster economic growth. This changed with the advent of the ‘basic needs’ and ‘redistribution with growth’ narratives, which informed the creation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). This narrative viewed ‘human needs’ as ‘human rights’ and replaced the earlier paradigms that emphasised on the means (i.e. growth) rather than the end (i.e. well-being). Successively, the financial crises of 2007 and 2008 initiated attempts to search for a new ‘big idea’ under the umbrella of the ambitious Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. The estimated ‘price tag’ for the realisation of these SDGs by 2030 would necessitate the mobilisation of US $2.5 trillion per year through Official Development Assistance (ODA) and private flows. On the other hand, the contending narratives of reducing ‘Aid Dependency’ in the Global South prompts us to evaluate the most fundamental question, ‘Is Development Aid still relevant?’ This essay attempts to systematically evaluate the debates around four key issues—aid effectiveness, emergence of new donors, composition of aid, and the change in the nature of aid, from an economic to a political and security agenda in order to understand the relevance of aid in contemporary times.

The link between international aid and development

The hot debate between aid optimists and pessimists can provide a framework to evaluate aid effectiveness and relevance. There are several criticisms of aid stemming out of—the faulty architecture, mismanagement, volatile nature, opacity, high selectivity of geo-politically favorable regions, and the top-down hierarchical approach of international aid which result in context blind development projects. It is believed that aid to Africa is characterized by ‘authoritarian paternalism’ and ensures that Africa remains perpetually in an infant-like state. On the contrary, proponents of aid would suggest that aid is instrumental in uplifting the standard of living and setting economic progress into motion. Also, a ‘big-push’ is required to overcome the obstacles of poor agricultural productivity, poor health, and education, etc. to overcome the impediments to growth that capture these countries in a poverty trap. Consider Botswana, Africa’s growth miracle, it has received more aid per person than an average low- income country by eight times. More recently, the income per capita in large recipient countries like Mozambique and Uganda has doubled since 1990s. Moreover, since 1960s, the average real income of Egypt has increased by three times while the infant mortality rate has astonishingly dropped from 189 to 35 per 1,000 live births. This has been corresponded by the doubling of literacy rates in the country. Since ‘evidence beats rhetoric’, it prods us to think that aid is still relevant in terms of its positive effects on growth and poverty reduction.

The emergence of ‘new donors’

The relevance of developmental aid has increased with the emergence of new donors like- Brazil, India, and China outside the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), marking a silent revolution in the arena of development aid and assistance. Debates in this sphere highlight the contending narratives of neo-imperialism of rising powers and South-South cooperation. On one hand, it is noted that aid from new donors like Brazil and China are often decontextualized and propagate a set of alien prescriptions incongruent to the realities. In Africa, Chinese development aid upholds the principle of ‘non-interference’ and ‘non-conditionality’ in the domestic economico-politico affairs of the recipient country. However, it deploys economic restrictions by tying the contract with the exclusive use of Chinese labour and equipment. On the other hand, the misperception of China as a rogue donor stems from the inability to distinguish China’s ODA from Other Official Flows (OOF). While the former is provided at a concessional rate to advance political agendas, the latter is provided at a near market rate to promote economic interests. Moreover, China is merely pursuing a strategy of influence as opposed to conditionality and interference. The emergence of new donors has also enabled developing countries to look beyond the DAC for technical and financial assistance and questioned ideals embodied within the Washington Consensus. Therefore, on balance, the addition of new players in the development field has increased the relevance of aid by causing a shift in the global power structure, reducing dependency, and increasing the amount of aid at the developing countries’ disposal.

Composition of international capital flows

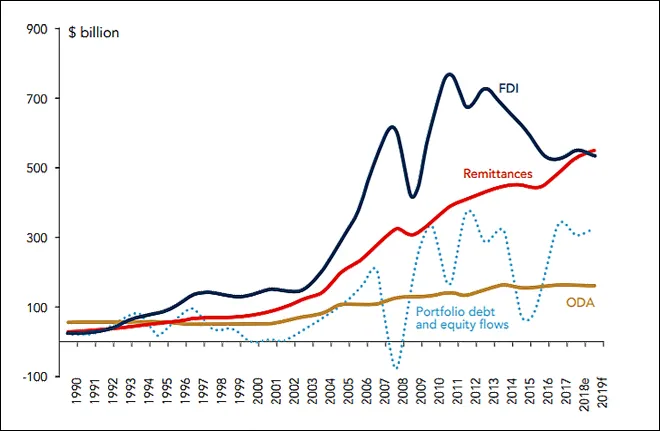

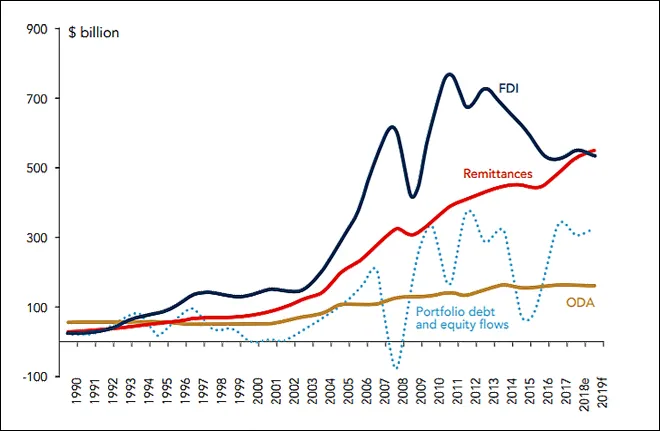

Since 1995, remittances have overtaken ODA as one of the largest sources of capital inflow to developing economies which questions the viability of development aid in light of the enormous availability of remittances (Refer to Figure 1). One school of thought suggests that remittances are more effective in fostering savings and investment, as in the case of Sub- Saharan Africa. Also, unlike remittances, aid has negative effects on growth as it weakens the capacity of the state to collect revenue (the Dutch disease) and dampens the tradable goods manufacturing sector through overvaluation of currency. The other school of thought suggests that official aid is more effective in bolstering economic growth because remittances face the problem of uncertainty due to capital restrictions and are often undocumented. The third camp indicates the complementary nature of the two where an increase in remittances could enhance the growth effect of official aid. It could be said that unlike remittances, aid channelizes funds in priority sectors and is more manageable through bureaucratic administration. It also plays an important role in pulling households above a threshold income level to ensure that additional remittances are invested productively to enhance growth, thus, hinting towards the complementary relationship of aid and remittances. Therefore, the relevance of aid is not challenged by the growing amount of remittances.

Figure 1: ODA, Remittance and Private Capital Flows from the Global North to the Global South (1990-2017)

Source: World Bank Group

Source: World Bank Group

Transformation in the nature of aid

Aid is a polysemous term and has transformed from being an economic agenda to a political and security agenda. It is often suggested that economic transformative goals can be realized when seen as being embedded in political realities. However, the post-9/11 declaration of ‘war on terror’ has increasingly linked developmental problems in the Global South to security issues to the Global North, a conceptualization which can have adverse effects on global security and global poverty reduction. While securitisation of aid is highly contentious, it has led to the channelization of 67 percent of ODA to fragile contexts. This is evident from the increase of US aid to Iraq from 5 percent to 25 percent during the war and the deployment of Provincial Reconstruction Teams for improving stability, protection, and security systems. Moreover, aid under the Commander’s Emergency Reconstruction Program was used in 11,000 development projects. Therefore, while there has been a change in the nature of aid from an economic to a political and security agenda, there has also been a corresponding increase in the channelization of ODA to fragile contexts.

Can development aid be ‘made’ relevant?

Development aid can be ‘made’ relevant and effective by undertaking various political, social, and economic measures. This can be understood by the measures taken by Rwanda and South Korea. In Rwanda, the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy was devised to decrease aid dependency from 86 percent in 2000 to 43 percent in 2012. This was achieved by effective public finance management, accountability of aid use through target setting and result achievement and bureaucratic transparency. Concomitantly, there was a large decline in infant, maternal, and malaria-related mortality and increase in access to health and education. South Korea also provides a blue-print for effective aid utilisation which led to the rapid economic recovery under the Syngman Rhee regime and modernisation under General Park Chung Hee. About 87 percent of the total aid was channelized towards the industrial sector—particularly mining, transport and manufacturing. State played an important role in the military-industry nexus and military aid encouraged development in conflict-free areas. The South Korean experience resonates with the idea that aid works where there are good policies and institutional quality.

In conclusion, an attempt has been made here to establish the relevance of aid by carefully analysing four factors—aid effectiveness evaluated in terms of propelling economic growth, the emergence of new donors like Brazil, India, and China, the changing composition of international capital flows from the Global North to the Global South and the changing nature of aid- from economic to security and political terms. Aid still seems relevant because—there’s overwhelming evidence of the positive effect of aid on growth; aid from emerging economies changes the global power structure and reduces the dependency of the developing countries on the developed countries. The complementary relationship between aid and remittances can facilitate the achievement of tangible development outcomes and securitisation of aid can be helpful in providing assistance to fragile contexts. Drawing from examples of Rwanda and South Korea, it becomes clear that good policies, institutions as well as bureaucratic accountability and transparency are able to ‘make’ aid relevant and effective.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: World Bank Group

Source: World Bank Group PREV

PREV