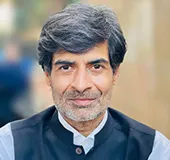

The following is a recent interview of Samir Saran with Valdai Club. Saran shares his view of the emerging Asia-centric world order and Russia’s place in it.

“Russia always identified itself as a European power, and Eurasia was a compromise,” he said on the sidelines of the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok earlier in September. “It is now starting to see itself as a key actor, interlocutor and power in the Asian century.”

“Russia is a continental and maritime power simultaneously,” said Saran. “Which is why there can be no Asian order without Russia being a central part of the bargain,” he added. “There can be no Eurasian integration, and no Pacific or Arctic arrangement without Russia having an important stake in framing the rules.”

According to Saran, Russia must closely consider whether it is prepared to play this role. “Sometimes I think that Russia does not fully realize its own potential: it often sees itself as a disruptor; but not as a manager — a benefactor that must sustain and stabilize the system,” he pointed out.

“For that to happen, Russia’s economy has to grow in the coming decade to about four trillion dollars. Otherwise, Russia will be tempted to play the role of a political interrupter rather than that of a political guarantor — a responsibility it must bear if it is be a consequential actor in the 21st century. To guarantee the Asian order, Russia will have to grow its ambitions, its economy and its institutions.”

That said, the two crucial powers defining the future Asian order are China and India. The question is whether they will try to create something new or adopt existing institutions and practices. According to Saran, the answer is both. “India and China have grown exponentially in less than three decades. India still has a journey to complete — maybe another 15 years before it becomes a 10 trillion dollars economy. Still, neither are fully capable of upending the rules of international institutions altogether. They will have to, in many ways, rely on the old ones, and maybe change and reform them.”

This means that the old institutions will work in new ways. “If one looks at some of the Western institutions like the OECD, the UN, and the World Bank — many of them are operating in consonance with China’s infrastructure projects and international agenda,” Saran said. “In that sense, China’s rise has changed the very character of international institutions.”

According to Saran, the same will happen with India within the next 15 years: “Size matters, and both India and China have reached their critical point. It is impossible for the world to be stable and prosperous without these two actors having an important role in the order of things.”

However, it would be wrong to suggest that the Asian order will be dominated by a few powers. It should be more plural than the current one, Saran believes. According to him, it will take seven or eight countries for the Asian order to finally emerge. Apart from China, India, and Russia, these would include Japan, some of the ASEAN states, and possibly Iran and Saudi Arabia.

On the institutional level, “any organisation that allows the countries to talk and synthesize diverse political systems, economic models, and ideas on peace and security will work,” Saran said. But since Asians are “highly sovereign,” any such arrangement has to be democratic and plural; it must be based on the “one country-one vote” principle.

Asked if the Shanghai Cooperation Organization could serve as a prototype for such an institution, Saran said that in its current version it is a “good beginning.”

“I think that institutions like the SCO are important, but this does not mean than the SCO is the best option. If is starts serving only Shanghai, then it will lose its meaning. But if it becomes a ‘round table,’ where seven or eight large countries could sit down and discuss key questions, then it is becomes useful and meaningful,” he pointed out.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV