The novel coronavirus has put the world in unchartered territory. The outbreak of the virus and the associated diseases has put citizens and decisions makers in a state of panic. As to be expected of any infectious disease, number of confirmed cases and deaths continue to surge. Even the strong medical infrastructures risk nearing exhaustion. And while a thorough evaluation of the health consequences induced by COVID19 is still ongoing, numerous countries have already adopted stringent suppressing measures to curtail the spread. Among them, the “lockdown” strategy has emerged as a one-size-fits-all approach that requires critical evaluation.

The case for emerging economies

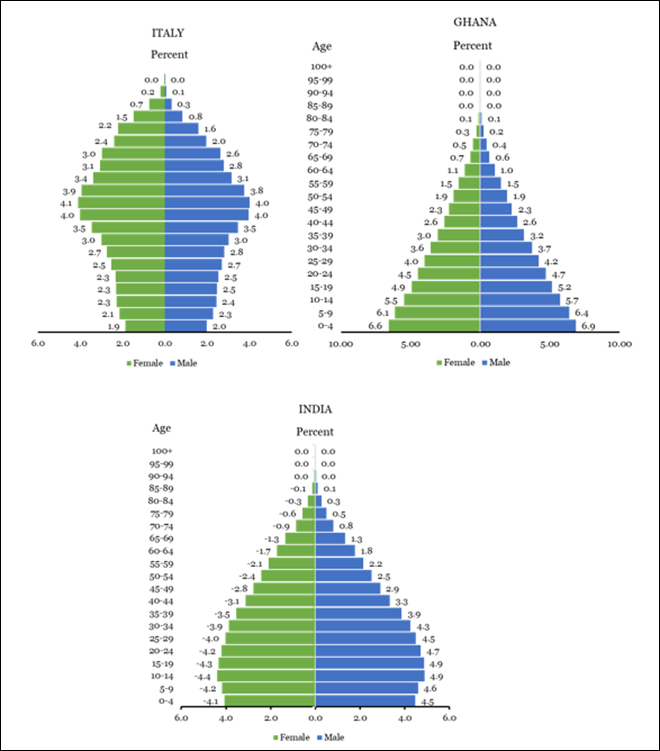

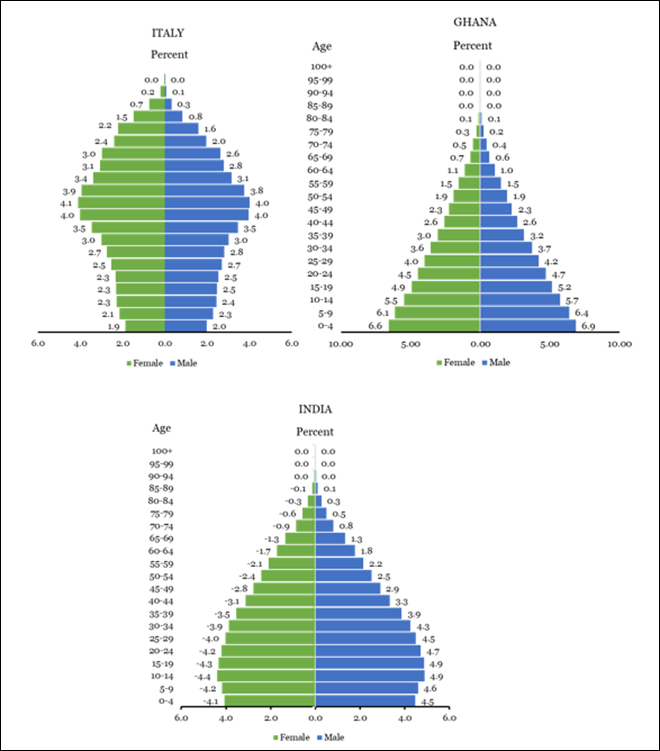

The current trend of COVID19 related mortality rates tends to suggest that for some economies, especially those in emerging markets, measures involving a far-reaching lockdown may not necessarily be the optimal responses in dealing with the pandemic. Recent data suggest that the high-risk group is mainly comprised of the elderly, especially patients with pre-existing medical conditions. Hence, a look at the age structures of two emerging markets, Ghana and India, unveils a potential silver lining when estimating the negative impact of COVID19 on such societies (see Figure 1 for a comparison of the demographic distributions of Italy, Ghana and India). Ghana’s and India’s population structures are both heavily skewed towards the bottom, around half of the respective demographic younger than 25. Given such demographics, the force of the negative health consequences could differ significantly, from what ageing European economies are currently experiencing.

The current trend of COVID19 related mortality rates tends to suggest that for some economies, especially those in emerging markets, measures involving a far-reaching lockdown may not necessarily be the optimal responses in dealing with the pandemic.

Figure 1: Population Structure of Italy, Ghana and China

We note that the hospitalisation of infected younger patients is not to be disregarded as the virus has been shown to seriously affect the health of younger persons also; especially as pre-existing medical conditions matter. However, up to this point, children and younger adults seem to have a significantly lower probability of severe or lethal consequences in comparison to the elderly.

Taking secondary impacts of current proposals into account

As experts begin to question the sustainability of current lockdown measures, and specifically the sustainability of them, it is essential for emerging economies to devise strategic responses that suit their specific contexts. Economies in emerging markets should be cautious in copying and adopting severe lockdown measures, which could, potentially, have a lasting long-term impact on their more fragile economies.

So far, reliable estimates for the case mortality rate (and the infection rate) of COVID19 are still scarce but are improving and we observe downward classifications of the dangers of the disease. In any, case death rates certainly lower than the estimated mortality rate of other communicable diseases like SARS or MERS and in particular Ebola. Consequently, the secondary effects of suppressing measures such as lockdowns need to be taken into account, especially in emerging markets such as India. One might even observe a potential flow of power to the powerful. As such, experts have already begun to raise issues of institutional risks and power grabbing in some younger democracies in the global north such as Hungary.

It is of little doubt that a significant part of the population, if not the majority, will eventually be infected unless there is a vaccine or even more drastic public health measures. As we hope for a permanent solution, the societies in emerging markets with young populations must now select appropriate measures. As a way forward, decision-makers should seriously weigh the trade-offs of wide-reaching suppressive measures. A breakdown in the supply of essential services might plunge the already constrained health facilities of transitioning economies into an even more severe crisis. For instance, the closure of public sanitation facilities could encourage open defecation and roll back the gains, which have already been made, in many related areas. Supply of potable water may be affected if lockdown measures continue in their current form. Panic reactions and the potential lack of international support structures might threaten the re-emergence of other local disease outbreaks. We have to remember that many of the poor have no means to use soap regularly. In addition, the few means they have may be lost due to lockdowns. In 2017, poor sanitation accounted for nearly 5% of all deaths in low-income countries and as high as 11% in Chad. We risk exacerbating these figures if we are not careful with the current COVID19 outbreak and the suppressive measures taken.

It is of little doubt that a significant part of the population, if not the majority, will eventually be infected unless there is a vaccine or even more drastic public health measures. As we hope for a permanent solution, the societies in emerging markets with young populations must now select appropriate measures.

In a different vain, preventing people from working who directly depend on their daily wages without substantial savings is associated with high risks for their health and the stability of society in general. Plans in some emerging economies to shut down public markets threatens the food supply, which could create a nutrition crisis with significant human capital costs. Already, economists are warning of possible starvation due to the pandemic and, the subsequent lockdown in India, which has a population of over 1.3 billion and experienced mass migration.

As it stands, the primary problem of the pandemic in emerging markets may not be the number of infected people, but rather, weak health systems and the unintended secondary impacts of lockdowns. A healthy population is a good with a high value, but a strong economy has systematically been closely linked to the health of its citizens and their life expectancy. Pandemics are not only a biological event and a public health disaster, but it is essential to understand and fight them from an economic, societal, and cultural perspective.

A potential way forward

Young populations in emerging markets offer a chance to investigate and exploit medically and economically sustainable solutions to the problem. Nations in the sub-region could follow the recommendations of Eichenberger et al. (2020) in identifying people who have undergone COVID19 and acquired immunity. This need not be an individual country effort, but the various regional bodies could coordinate efforts. The current lockdowns may be inefficient since those who have been infected and recovered stand a little chance of re-infection as immunity to the disease is more likely. It will benefit economies to search and certify these immune individuals so that they can go back to their usual economic and social activities. It is, therefore, prudent management of the situation to channel some resources and attention in search of these people in society.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV