-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Carrie Lam’s tenure marks Hong Kong’s tighter embrace with mainland China.

Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam will not be pursuing a second term in office. She leaves behind a legacy of a divided society scarred by widespread protests, an enervating COVID wave that saw record fatalities, and an exodus from the city-state.

She spent nearly four decades in Hong Kong’s bureaucracy, rising to the post of Chief Secretary—the senior-most principal administrator of the special administrative region’s government. This government stint helped her in getting a ring-side view of the island’s politics, which ultimately came in handy when she made a pitch for the position of Hong Kong Chief Executive in 2017.

Lam invariably leaves behind a legacy of altering the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ framework that underpinned relations between mainland China and the Hong Kong special administrative region. Besides greater integration with mainland China, her tenure was marked by intense securitisation of Hong Kong’s society.

The United Kingdom (UK) handed over Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 on the arrangement that it would be governed under the ‘One Country, Two-Systems’ framework. This meant that the island would enjoy autonomy and get to retain its capitalist system under the larger umbrella of Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) rule, in which the latter handled its defence and foreign affairs. The CCP went along with this arrangement since it believed that this framework would someday entice Taiwan to come back to the mainland. However, the CCP always been distrustful of Hong Kongers despite them cheering the handover. Deng Xiaoping wanted his compatriots in Hong Kong to be patriots first. Deng said he wanted patriots at the helm of the island’s affairs, who had respect for the Chinese nation and who desired a stable Hong Kong.

Lam invariably leaves behind a legacy of altering the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ framework that underpinned relations between mainland China and the Hong Kong special administrative region.

Suspicions over the loyalty of the island’s population has prompted Beijing to subtly alter its demographics. The one-way permit scheme, which allows mainland Chinese to reunite with their kin living on the island, has resulted in an influx of more than 1 million mainlanders since the handover. This influx has contributed to 90 percent of the city-state’s population increase in recent years. Surprisingly since the handover, it seems like Cupid has struck more often adding to the influx into Hong Kong. A year before the handover, marriages between mainland Chinese and Hong Kongers were barely 7 percent of the total number registered in Hong Kong, in 2018, this figure stood at nearly 33 percent. The fact that only around 21 percent of the migrants over 15 years of age in the one-way permit scheme have completed secondary school education, and nearly 50 percent of the adult population in the reunification scheme have a job seems to have fuelled Hong Kongers’ antipathy towards migrants from Beijing.

Changes in demography are known to trigger local reactions. In this case, the response to the influx is crystalised around a strong ‘Hong Kong identity’, and mass movements for political reform. A survey conducted by the University of Hong Kong in 2019 revealed that only 11 percent of the interviewees mentioned their identify as ‘Chinese’—a record low since the handover. The poll recorded that the number of respondents who identify themselves as ‘Hong Kongers’ was 53 percent—the highest tally since 1997. Since the 2000s, protestors hit the streets on several occasions seeking political reform.

These developments cast a shadow on Lam’s tenure, and her administration, and Beijing stepped up efforts to integrate with the mainland, which had its impact on the ‘One Country, Two-Systems’ framework. Beijing was working to bridge the distance with the island. Hong Kong was linked with China’s high-speed rail network in September 2018. Close on the heels of this, a sea-bridge connecting Guangdong on the mainland with Hong Kong and Macau was inaugurated. In February 2019, the CCP unveiled its economic blueprint to bind the region closely to the mainland in the form of the Greater Bay Area project, an economic zone comprising Hong Kong and Macau, and nine cities in Guangdong province. In 2019, Lam’s administration brought in a legislative proposal that would have permitted extraditions to mainland China. Mass demonstrations later forced her to withdraw the bill, but regular protests continued against Hong Kong’s increasing embrace of the mainland.

A survey conducted by the University of Hong Kong in 2019 revealed that only 11 percent of the interviewees mentioned their identify as ‘Chinese’—a record low since the handover. The poll recorded that the number of respondents who identify themselves as ‘Hong Kongers’ was 53 percent—the highest tally since 1997.

However, the wheels had been set in motion. In June 2020, Beijing circumvented the Hong Kong Legislative Council to promulgate the National Security Law, which proscribes acts that the CCP describes as secession, sabotage, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces. In 2021, Lam cleared an electoral representation law that instituted a committee to vet candidates running for public office, so that only ‘patriots’ rise to positions of power, thus fulfilling Deng’s wish. Under her tenure, the mainland’s Office for Safeguarding National Security, an agency instituted under the national security law, ramped up its presence on the island. The agency is tasked with monitoring and providing inputs to the Hong Kong administration in enforcing the national security law. It is also responsible for vetting candidates for Hong Kong’s legislative and Chief Executive elections. Through the legislation and the agency, Beijing is able to get a vice-like grip on Hong Kong’s polity.

Lam perhaps thought that keeping Beijing in good humour would go a long way. She travelled to Beijing in July 2021 for the CCP’s centenary celebrations, this was the first time when a Chief Executive skipped the official commemoration of the city’s 1997 handover, demonstrating to Hong Kongers where her priorities lay. Under her watch, Hong Kong police switched to a new goose-step marching style in sync with the pattern followed in mainland China from British-style foot drills. The natural fallout of this has been intense securitisation of Hong Kong’s society in Lam’s tenure. This can be evidenced from the Hong Kong administration high-pitched commemoration in 2021 of the ‘National Security Education Day’ in schools for the first time since the handover.

The reconfiguration of relations between Beijing and Hong Kong are having significant repercussions. Foreign judges adjudicate in Hong Kong courts and this has long been seen as a hallmark of the rule of law after Hong Kong’s return to China. In March 2022, two judges from the UK’s Supreme Court announced that they would not serve anymore in Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal, citing the national security legislation. Not just jurists, but even ordinary Hong Kongers are making a beeline to the exit.

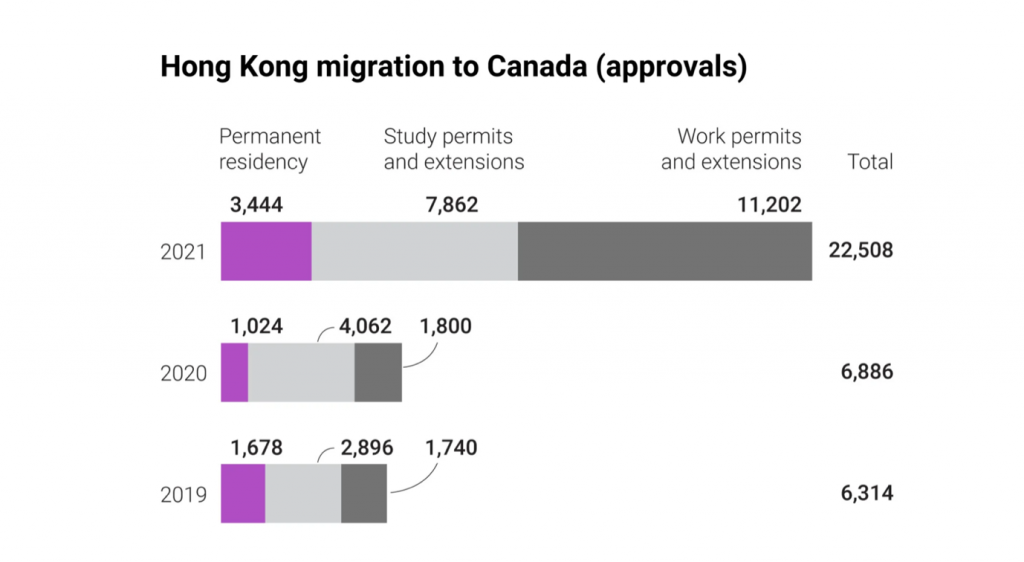

(Source: Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada)

In 2021, under the scheme put in place by the UK in response to the National Security Law, more than 97,000 visas were granted to Hong Kongers. The exodus from Hong Kong to Canada has risen to record levels. Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada statistics reveals that more than 22,000 Hong Kongers obtained permanent residency in Canada, work or study permits in 2021, an increase of 250 percent from 2019. This demonstrates that across students and professionals alike, they see little future for themselves on the island with China’s increasing grip.

The choice of figures with deep ties to the establishment or security services suggests that Beijing believes that that Hong Kong could be used as a bridgehead by the West against the CCP, and hence efforts to subsume Hong Kong will continue beyond Lam’s tenure.

Hong Kong’s polity in the post-Lam era does not look very promising. The ‘patriots-only’ principle and the electoral changes of 2021 have neutralised independent voices. Lam promoted figures associated with the law-enforcement establishment. Secretary for Security, John Lee, was elevated as the Chief Secretary, making it the first time that an official with ties to the law-enforcement establishment has been appointed to the top bureaucratic position. The fact that Lee is the frontrunner, who has the CCP’s blessings to step into Lam’s shoes, is a pointer to the times ahead for the island. Chris Tang, who helmed the island’s police force that was at the forefront of the crackdown on pro-democracy activists, has been made Secretary for Security (John Lee’s previous portfolio). Former Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-Ying, who serves as the Vice-Chairperson of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (China’s top political advisory body), is tipped to be the Chief of the Election Committee, which will decide the island’s next leader. The Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office (HKMAO), an agency that assists Beijing in dealing with matters related to the special administrative regions, has been headed by Xia Baolong, who was responsible for razing Christian churches on the mainland. Xia is an ally of CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping, and Xia’s recently appointed deputy in the HKMAO, Wang Linggui, is an expert in national security. The choice of figures with deep ties to the establishment or security services suggests that Beijing believes that that Hong Kong could be used as a bridgehead by the West against the CCP, and hence efforts to subsume Hong Kong will continue beyond Lam’s tenure. Thus, Lam’s tenure will go down in Hong Kong’s history as an important inflection point in the evisceration of its society.

Richard Evans, Deng Xiaoping and the Making of Modern China (Viking Penguin, 1993), pp. 269-270.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Kalpit A Mankikar is a Fellow with Strategic Studies programme and is based out of ORFs Delhi centre. His research focusses on China specifically looking ...

Read More +