-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

As the Loss & Damage Fund stalls, India must turn to parametric insurance—backed by central model guidelines—to shield vulnerable communities from climate-linked losses.

Image Source: Getty Images

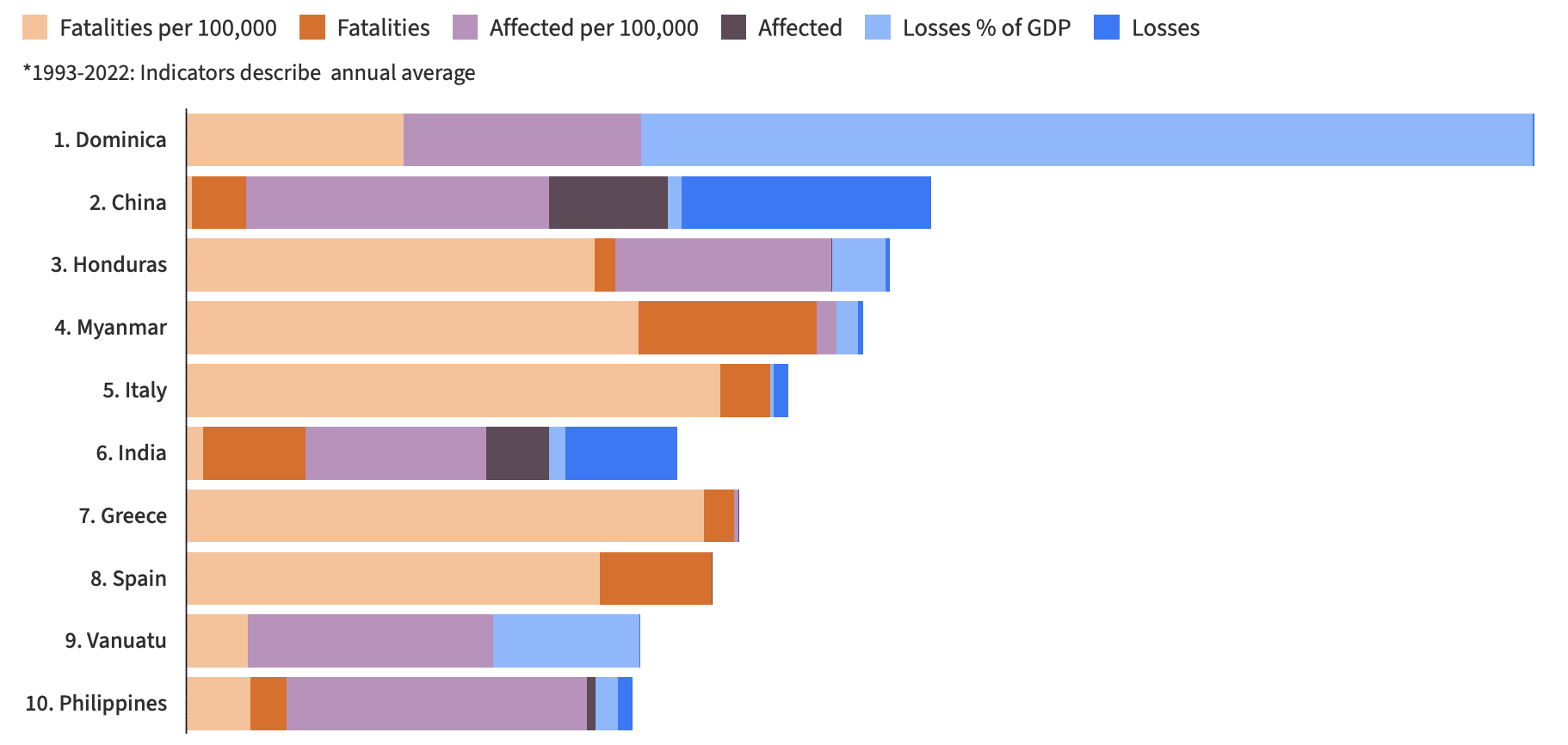

According to the 2025 Climate Risk Index, India ranks sixth among the top 10 countries affected by extreme weather events (Figure 1). Exposure to climate-induced disasters has increased dramatically in recent years, with extreme events causing US$180 billion in losses across India since 1993. Yet, over 90 percent of natural disaster exposures are uninsured, as the traditional disaster risk financing is no longer adequate. The growing frequency and severity of extreme events demand faster, more reliable, and scalable protection mechanisms.

The Loss and Damage Fund (L&D fund)—established during COP27—represents a long overdue milestone in climate justice. The Fund is designed to offer assistance to countries suffering from irreversible climate damage, and aims to bridge a major gap in the climate finance architecture. However, the global community is facing significant hurdles in operationalising the fund, including disbursement delays, complex loss verification processes, and unpredictable funding. These bottlenecks risk eroding trust in the L&D fund, especially in developing countries that cannot afford long waits for relief.

Parametric insurance mechanisms offer a viable, rules-based safety net, which can both complement the L&D Fund and help close India’s protection gap. To build true climate resilience, protect vulnerable communities, and sustain long-term development, India must prioritise integrating such innovative financial tools into its disaster risk strategy.

Figure 1: Climate Risk Index: Top 10 Most Affected Countries

Source: GermanWatch 2025

Parametric insurance is different from traditional models as it offers payouts not on actual loss assessments, but on the occurrence of a predefined parameter. In India, parametric insurance has been tested in several instances. It has been used to cover income losses for outdoor workers during heat waves and for dairy farmers facing milk yield loss during summers. In 2024, Nagaland became the first Indian state to launch a multi-year, government-backed scheme to implement parametric insurance at scale. However, while such developments are promising, they remain isolated, and several barriers limit the scalability of parametric insurance.

Despite its potential, the uptake of parametric insurance remains limited to small-scale projects, which reveals a core challenge: the scaling paradox. Parametric insurance is the most effective at scale for addressing systemic risks, as larger pools allow insurers to better price risk, lower premiums, and negotiate favourable reinsurance. Yet, in India, it remains trapped in a pre-scaling loop. Most schemes have limited geographic coverage and short time horizons, and such fragmentation can raise costs and erode trust among insurers and clients alike.

India ranks sixth among the top 10 countries affected by extreme weather events. Yet, over 90 percent of natural disaster exposures are uninsured, revealing a critical protection gap in the country’s climate finance architecture.

The following interlinked challenges compound this issue.

1. Regulatory and Institutional Gaps

Despite recent progress, regulatory ambiguity remains a barrier to scaling parametric insurance in India. A core challenge is the uncertainty surrounding permissible funding sources for premium payments under government budgets. The Nagaland insurance initiative, which insures against excess rainfall through the State Bank of India (SBI) General Insurance and Munich Re, has been replicated by a few states due to a lack of clarity on how to finance premiums. Stakeholders also note that broader integration will require concrete policy guidance. States need a unified institutional framework that formally recognises parametric instruments and specifies how premiums should be financed. While the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) permits insurers to launch parametric products under the ‘use-and-file’ regime, it remains underutilised, in part due to low awareness among insurers and state governments.

2. Data Dependence

Effective parametric insurance relies heavily on the availability of high-quality, real-time environmental data. Inaccurate and unavailable data can also cause a mismatch between the index and actual losses experienced by the insured. In Nagaland, during the pilot insurance rollout (between 2021 and 2023), a major failure happened when, despite heavy rainfall and floods, no payouts were triggered because the threshold was set too high. This was caused due to the satellite data being significantly different from ground reality and the data received from the India Meteorological Department. Without spatially granular and verifiable data, affected communities may suffer losses without payouts.

3. Basis Risk and High Premiums

One of the biggest challenges is that of basis risk, i.e., the mismatch between actual loss and payout, resulting in the policyholder receiving a lower payout than expected or no payout at all. This misalignment can reduce public trust, especially in settings where insurance logic may be poorly understood. In addition, due to the higher risk borne by insurers and the many steps involved in designing parametric insurance, premiums are higher than more conventional forms of insurance. Without pooled risk across districts or states, insurers are unable to offer competitive pricing, leading to heavier reliance on philanthropic funds to help finance the cost of premiums.

The challenges faced by India in scaling parametric insurance mirror the broader limitations of global climate finance mechanisms such as the L&D Fund. The L&D fund’s bureaucracy, heavy reliance on indemnity-based assessments, and funding unpredictability imply that relief often arrives after the most acute period of need has passed. Similarly, limited scale, data constraints, and basis risk have restricted the scale of parametric insurance. This convergence of limitations presents an opportunity for integrated climate risk financing solutions. Parametric insurance can function as an interim, rules-based funding layer, which injects liquidity into disaster-hit communities. The L&D Fund can act as a backstop layer, and its resources can be mobilised for longer-term recovery and catastrophic events. A layered approach can mitigate long-standing delays and administrative gaps in the L&D Fund, and also reduce basis risk through coordinated risk assessments and data sharing. This layered integration can increase protection for vulnerable communities and enable India to align domestic innovation with evolving global frameworks.

A layered approach, with parametric insurance providing immediate liquidity and the Loss and Damage Fund supporting long-term recovery, can help close the protection gap and strengthen climate resilience.

The following steps can help make parametric insurance an effective complement to the L&D Fund.

1. Greater policy support

Firstly, states will benefit from clear guidelines on how to design, procure, and finance parametric insurance. There is a strong case for issuing central model guidelines—building on the 2024 clarification by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the Department of Financial Services—that State Disaster Mitigation Funds (SDMF) may be used to finance insurance premiums. At the national level, the IRDAI’s ‘use and file’ system must be widely disseminated through capacity-building for state governments and insurers. The creation of a dedicated platform can also help standardise policy guidance.

2. Investments in data infrastructure

An open-access data infrastructure, including historical and real-time weather/climate data, and partnerships with academic institutions or private analytics firms, can help reduce basis risk and build public trust in parametric insurance. Pre-validated parametric triggers for key climate events (for example, excess rainfall, drought, heatwaves, and cyclone windspeed) can also assist insurers and state authorities in faster and more reliable product development, and help align with L&D Fund loss categories.

3. Promotion of regional risk pooling and subsidised market entry

To lower premiums and expand coverage, India should promote risk pooling across states. For instance, states with common climate risks, such as Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu, could engage in parametric reinsurance pools. The central government can also offer subsidies for first movers, potentially through the National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change (NAFCC) or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)-linked climate finance.

As India faces a growing frequency and intensity of climate-induced disasters, increasing the scale of innovative financial tools has become critical. Parametric insurance offers a viable pathway to address the country’s low disaster insurance coverage by enabling faster, rules-based payouts. Despite the government’s 2016 ten-point agenda on Disaster Risk Reduction, which emphasised the importance of ‘risk coverage for all, starting from poor households to SMEs to multinational corporations to nation states,’ parametric insurance remains limited. Similarly, the L&D Fund, a milestone for global climate finance, continues to struggle with problems constraining timely funding flows. Integrating parametric insurance into the L&D Fund’s operational architecture can help bridge this gap and ensure timely relief reaches those in need.

Abhishree Pandey is a Research Assistant at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Abhishree is a Research Assistant at the Centre for Economy and Growth in New Delhi. Her areas of interest include climate policy, energy, and adaptation ...

Read More +