-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

In recent weeks, particularly following the National Suppliers’ Group (NSG) plenary in Seoul, India-China relations have become testy. Several reasons have been attributed to this and it is possible all of them have had a bearing on the outcome.

Critics of the Indian government’s attempt to gain acceptance as a full member of the NSG have blamed it on motivation. They have argued that the bid was premature and grossly underestimated the Chinese ability to veto India’s entry, or Beijing’s ability to stand up to a request from Washington DC. In 2008, when it had come to granting India a waiver for nuclear commerce, the NSG had been swayed by the United States and China had retreated. Eight years on, it’s a different world.

Subsequently, Indian officials and even the Indian external affairs minister have been quite explicit in identifying the Chinese as the one or at least the principal and determining roadblock at the NSG. It is a fair assessment that, without China’s veto, the procedural and technical questions raised by a few other countries may have evaporated. In a strict “yes-no” situation, New Delhi is confident that these countries would have backed India; and that Beijing’s veto prevented the occurrence of that strict “yes-no” situation.

Since then, the mood has been tetchy. Indian officials have argued that it was the Chinese who actually singled out India, in an on-the-record statement, well before India had singled out the Chinese. In Seoul itself, the Chinese chief negotiator clearly told the media that the NSG would not be allowed to accommodate India unless New Delhi signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It was a bald statement, not couched in any vague language about seeking a “procedure” or “general principles” for “expansion of membership”.

Following this, there was a familiar battle between sections of the Indian media and Chinese commentators, both of whom may well have been reflecting positions of national foreign policy establishments. Matters were escalated somewhat when Chinese diplomats in India went out of their way to dismiss India’s NSG candidacy and were rather harsh in their expressions against the country they were serving in.

India’s response was oblique and included refusal to extend the visas of a set of Chinese journalists who had been staying in India for a considerable period — in one case for seven years, with month-by-month visa extensions towards the end — and who seemed to be fulfilling a “dual purpose”.

After the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruled against China and in favour of the Philippines in their South China Sea dispute, India issued a nuanced and well-drafted statement affirming its faith in the Court’s verdict. What is less known is that a familiar set of China watchers and “friends of Beijing” in New Delhi privately urged the Indian government to not issue a statement following the PCA judgement, insisting India should express no opinion and it was not concerned with the South China Sea dispute. Such a suggestion was, of course, a non-starter. Even so, it did give an indication as to influential thinking in the Indian establishment during the course of the past decade.

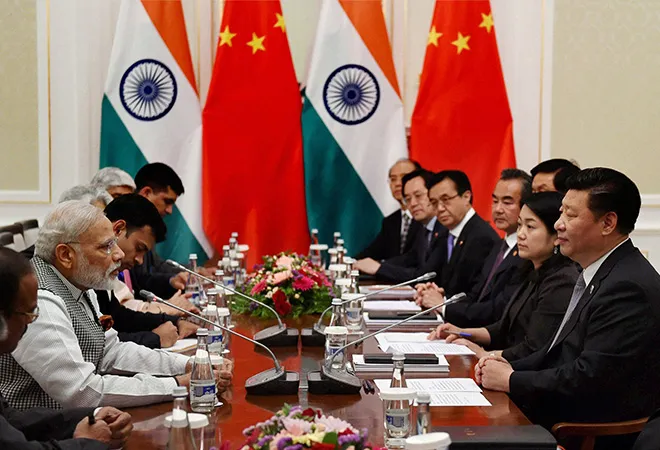

Despite this near-term history, it is not as if India-China engagement is only bad news. Outlook for the business relationship remains positive, especially as the Indian infrastructure story gradually gathers pace and demand in the economy expands. This will create markets for Chinese products and companies and Beijing is mindful of that. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to China later this year for the G20 summit could also be used by both countries to remedy the atmospherics.

Having said that, the shadow of a third country is clearly being felt on India-China bilateralism. This is not so much a reflection of India’s growing strategic proximity to Japan or the deepening of the relationship with the United States under the Modi government. While China does tend to take India that much more seriously at junctures when it feels New Delhi and Washington, DC, have that greater degree of alignment, it recognises that despite the scare-mongering and the occasional media frenzy, there is little chance of a “containment” policy in the region and of India joining political or military alliances aimed expressly at isolating China.

The locus of the India-China distrust, perhaps of its immediate manifestation, seems to be in Pakistan. To be precise, it is in the area of Kashmir occupied and controlled by Pakistan. As details of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) are emerging and as actual construction is being monitored, it is becoming obvious to Indian officials that some of the roads and facilities being built in the Pakistan-held Kashmir region scarcely have a commercial or trade purpose, and are not critical to a pure trade corridor to the Arabian Sea.

They seem to be designed to support military logistics and, in terms of the landscape of warfare, integrate China and Pakistan that much strongly. In a sense, both countries are seeking a strategic depth in each other’s territories, and there can be only one possible target.

In private, India is bringing this up with the Chinese and with other international interlocutors. The creation of hostile military-use installations in what is at the very least internationally recognised as disputed territory is a potential embarrassment for the Chinese. In the past year, aware of the propaganda potential being handed to the Indians, the Chinese have been pressing the Pakistanis to “sort out” the status of Kashmir, or that part of Kashmir that is in Pakistani control.

Now the tweaked strategy appears to be to brazen it out, and attack India publicly without quite answering how China justifies the CPEC’s route through territory that India sees at its own and that acceded to India — officially and legally, insofar as that matters — in 1947.

Pakistan’s recent belligerence on Kashmir too is being linked to this mood, rather than to, as has been commonly understood, the protests after the killing by Indian security forces of the Kashmiri militant Burhan Wani. In this context, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s rhetorical speech at a July public meeting in Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, wherein he spoke of the accession of all of Kashmir to Pakistan is telling.

It differs from more careful and deliberately ambiguous Pakistani remarks in the past few years that make reference to Kashmiris’ right to “choose”, to “liberty” and to “self-determination”. This has now been superseded by a blanket call for accession and thereby citing of a Pakistani claim on the entirety of the former kingdom of Jammu and Kashmir.

In such a scenario, Pakistan-controlled Kashmir becomes not Indian territory occupied by Pakistan (as India contends), not disputed territory (as many in the rest of the world believe), but legitimate Pakistani territory; the rest of (Jammu and) Kashmir becomes bona fide Pakistani territory illegally occupied by Indians. All this is clever semantics at best and fairly delusional. It does not change objective reality or the facts on the ground. Yet, it is Pakistan’s attempt to place a cloak of legitimacy on its use of Kashmiri territory for the CPEC — and to override Indian objections.

The Indian response, and the rest of the battle, is awaited. The Great Game of the 19th century is being renewed, with India and China as successor powers to the old empires of south Asia and Central Asia, and with the geography having shifted southeast.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Rishabh Kandpal Student Masters in Public Policy National Law School of India University

Read More +