This article is part of the series—Raisina Edit 2021

This article is part of the series—Raisina Edit 2021

The moment for a Tech New Deal is now

“The genie may seem to have come out of the bottle, but the Internet has surprised us many times.” — Tim Berners–Lee, Web Inventor (2018)

When the US suffered terrorist attacks in New York back in 2001, only five percent of the global population was connected to the Internet. At a key moment of its growth and design, the US passed a package of laws, including the USA Patriot Act, which weakened privacy in every aspect of American life and — as a result — in every aspect of our digital lives, as the most prominent companies were and still are under US jurisdiction.

In 2007, 17 percent of people were using the Web. That was the “Year of the iPhone,” when Apple co-founder Steve Jobs launched the company’s first mobile phones. The release of the iPhone was one of the most overt challenges to the original spirit of the Web invented by Sir Tim Berners-Lee. It was exactly the opposite to the principles the early Web embraced: Open, decentralised, permissionless, generative and for everyone. Yet iPhones, and the smartphones produced by Apple’s competitors, were the devices that really accelerated access to the Internet, bringing the Web to a more diverse set of people and geographies.

The release of the iPhone was one of the most overt challenges to the original spirit of the Web invented by Sir Tim Berners-Lee.

The death of the first phase of the Web started with the transition from multipurpose Web browsers to mobile applications (Apps), as people moved from personal computers (PCs) to mobile technologies and from open systems to locked devices. This curtailed the innovation and restricted the creativity so characteristic of the early Web, and, with its added layer of mobility, made users ever more traceable and identifiable. The adoption of mobile devices also accelerated the consolidation of power among the Big Tech companies. Locks, permissions, blocks in the road and police at the door (not to mention inside the new apps and platforms) were all imposed on users. It is possible that the adoption of mobiles led to a greater deterioration in the privacy of users globally than the enacting of the PATRIOT Act, because the rules against openness, the locks impeding innovation and the gates requiring identification were not written in law but baked into the code and the design of devices.

The deterioration of the principled Web became visible for the experts and activists after Edward Snowden revealed that a tool humanity conceived as a liberating force was actually restricting rights. The Internet was enabling an invasion of the private space of human beings as no actor had ever been able to before, involving public and private actors from the most powerful government in the world. Instead of celebrating the 25th Anniversary of the World Wide Web with fanfare, its inventor and many others, including heads of state and Parliamentarians in countries like Brazil and Germany rallied to restore privacy, at least in their jurisdictions. And then the explosion of the Internet of Things arrived, inheriting the same flaws embedded in code and law seen in the previous stages of the Web.

The Internet was enabling an invasion of the private space of human beings as no actor had ever been able to before, involving public and private actors from the most powerful government in the world.

In November 2018, the World reached an important milestone: Half of humanity was now connected to the Internet. The effects of massive connectivity, both local and global, are uncertain and cannot be isolated from the current social and political context. Autocracy is on the rise globally; the number of displaced people today is larger than the number displaced during WWII and only 4.5 percent of the world lives in a full democracy. The 26 richest people on earth in 2018 had the same net worth as the poorest half of the world’s population. That 26 includes the heads of the Big Tech companies, which — with less than half million employees — are looking to control the next billion people to be connected to the Internet, racing to capture the disconnected in their increasingly centralised platforms and harvest their data without knowledge or consent.

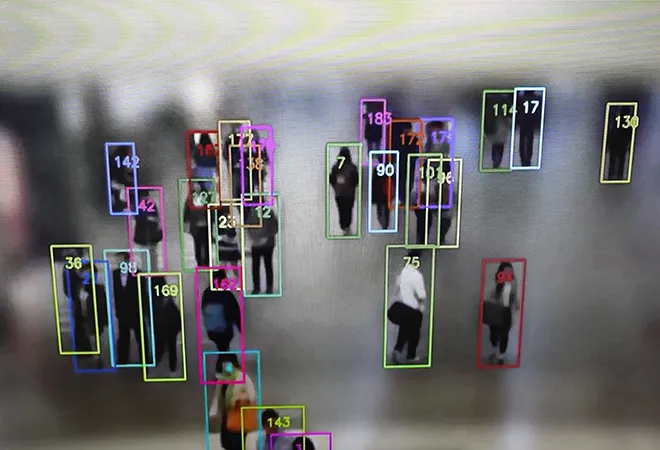

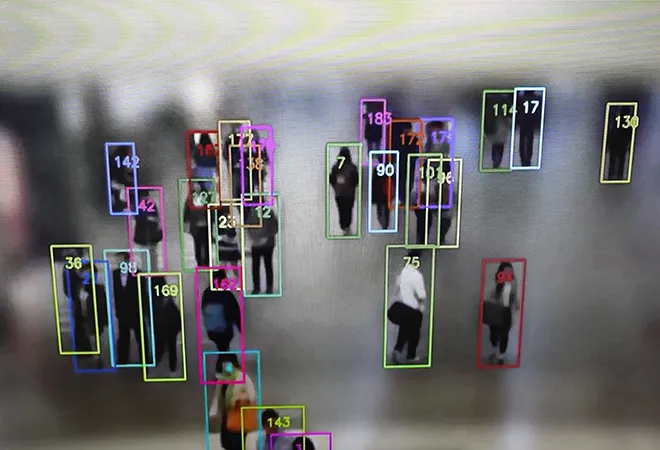

The architecture of the Web we have now is to blame for all this. The next billion Internet users are being connected to a controlled and centralised set of apps. The Web of the newly connected is ossified, organised and filtered, designed for a user to experience just a microscopic fraction of all the content available. On the other side of the device, companies will be intensely watching them all, all of the time. This is a window to a world of super customised reality and the constant extraction of data from subjects whose consent is at best dubious. The newly connected are unlikely to be aware of the scale of data that is to be extracted from them.

The Web of the newly connected is ossified, organised and filtered, designed for a user to experience just a microscopic fraction of all the content available.

The abuse is so widespread, so rampant. The abusers: Half a dozen companies in China, a dozen companies in the US. Hard to tame and extremely difficult to regulate, the abusers can easily be forced to act in the ways the most powerful governments in the world want them to act. They are, above all, keen collaborators and big profiters, refusing to embrace universal protections for all the citizens. The question is now whether a defence is viable and sustainable, from regional to national legislations, or even effective, or whether we should have a global conversation and a pact on the digital future we want.

We need a post pandemic Tech New Deal: A moment of coherence and international solidarity.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Internet and the digital life took a central stage. Tech billionaires got richer than ever, our rights were eroded globally, and technology delivered unequally. The lack of right frames and safeguards was as evident as the dependencies of entire countries on a handful of companies. Months after the pandemic, the cracks in the system are more than evident and us, connected citizens, global policy experts, scholars, entrepreneurs, activists, politicians are doing too little to reverse a trend of concentration of unaccountable power, profits for the few and no safeguards and rights for the many. We have been too distracted with words and manifestoes. Throughout the last decade there have been a number of attempts — more than thirty in fact — at creating globally valid digital constitutions with guiding principles for the Internet. The radical change we have seen in that timeframe is the ever-increasing scale of the governed and the shift of power away from them. Writers Lex Gill, Dennis Redeker and Urs Gasser, have observed that the tone of declarations has changed in tune with the way the Internet has become ever more entwined with our lives:

“It has become exponentially more difficult to distinguish between our digital and material lives. The way we engage with the Internet has countless and undeniable consequences for the physical world, and as the distinction between these two spheres becomes less relevant, the idea of a digital ‘wild West’ has also become less tenable.”

By our inaction and dispersion, we are somehow enablers of a dystopic digital future. We have answers waiting to be implemented, written in books and papers, shared at specialised fora, tweeted and preached. Often those are isolated and lack political teeth. We are doing too little and soon, it might be too late. The tech power is about to consolidate.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the Internet and the digital life took a central stage. Tech billionaires got richer than ever, our rights were eroded globally, and technology delivered unequally.

With more people connected and potentially affected by a Web without rights that is becoming ever more integrated with basic aspects of our daily lives, the idea of a Magna Carta, of a Tech New Deal, congruent and in synchronicity with a Green New Deal should not be abandoned. In an era where both code and law are weaponised by powerful actors, and fundamental rights are under attack, the design of this new pact must give consideration to each. A new design for a Digital Society that considers both code and law is the antidote against the weaponisation of everything. A Magna Carta, the Tech Neal Deal we dream of needs to cover more than just the right to our data. It must restore confidence in software, hardware and our ability to understand what machines are doing.

It is a moment of awakening, as we are still suffering a pandemic that made “digital” the daily real — exposing divides and flaws, glitches and abuse of power from tech companies, and discriminatory designs and authoritarian uses of apps and tracking systems. Citizens in several jurisdictions are rallying for regulation to tame the social and political impact of the big technology companies. This critical examination of the impact of technology on citizens’ lives and their health, not to mention the health of their democracies, has only started recently, and in just a few countries. But the outcry, with its demands to reclaim existing rights and assert new ones is growing rapidly. It could be transformed into a joint front for more and better Internet rights for all, a Tech New Deal, a new pact between those in whose hands power is concentrated and the people. It is my view that no democratic digital future is possible without universal digital rights, centered in people instead of technology.

The outcry, with its demands to reclaim existing rights and assert new ones is growing rapidly.

But if the pandemic exposed a global truth is that today we live in divided worlds, even within rich countries the digital divide exists; that the digital environment is producing augmented inequalities and that beyond its digital dimension, we are living in a crisis of trust of multilateral systems.

The post-pandemic period will accelerate connectivity. For half of humanity, finally having access to the Internet will be a new, life-changing experience. When this enormous population becomes connected and frequently updated about what is going on around the world, unpredictable things could happen. An awareness of inequality and its causes, if explained to those who just connected to the Web, could spark more anger and unrest than ever. However, with a good design in place, it could well be a catalyst for collective action to challenge the status quo and improve the well-being of everyone. Given the current state of connectivity, content and network architecture, profound change that favours democracy and the advancement of rights is unlikely to happen without intervention. That is why decisions concerning the way the disconnected are becoming the new connected, and the pace at which it is happening, are crucial for the future of humanity. The most vulnerable deserve to have access to a Web of rights. And all the actors involved should make a pact, a Tech New Deal, to make it possible, starting now.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series—

This article is part of the series— PREV

PREV