A major challenge faced in tracking progress across health and nutrition sectors is the unavailability of timely and quality data. In light of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as the national development agenda, India needs to boost its efforts. There needs to be an improvement in the volume, accessibility, variety and use of data, thereby making it easier for the common citizen to benefit from the open data initiative and ensure accountability. Progress has been made since 2012, but more can be done especially in the health sector to improve data collection and dissemination.

In 2011, 1.8 zettabytes (10^21) of digital data

was created worldwide. More data was generated in the last five years than was ever generated in all of collective human history. In India, business analytics companies aside,

a third of data analytics companies seeking financing were in the healthcare sector. Some of these companies have the low income population or the rural population as an intended beneficiary segment. Most of these companies use some form of government data.

The data being generated has started reaching the common citizens — though it is largely limited to educated, English speaking population with digital access. In India, it is happening through private sector — led data journalism portals and blogs like

SocialCops,

Factly, and

IndiaSpend etc. that keep facts and reliable data at the centre. The Indian government’s open data

website also hosts helpful apps like

Market Watch, which provides live price updates of commodities from various markets (mandis) across India.

In 2014, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon convened an Independent Expert Advisory Group (IEAG) to propose ways to improve data for achieving and monitoring sustainable development. The group recognised a need for

a data revolution to effectively ensure that no one is left behind in this process of achieving the SDGs.

Open data is at the centre of this revolution. The

concept can be traced to a theory developed in the 1940s by Robert Merton, a prominent American sociologist, who stressed the importance of knowledge that is free and accessible to all. Defined as

“data that can be freely used, reused and redistributed by anyone — subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and sharealike” it calls for data being available for free, or at a reasonable reproduction cost and without any discrimination or restrictions on its use.

The onus of facilitating this revolution falls on the governments, as they are the primary medium through which data collection is facilitated. Many national statistics offices adapt to this development by incorporating data from various wings of the government and making data human and machine-readable, ensuring an overlap between data release and policy making.

India’s progress so far

India’s

tenth and

eleventh five year plans (2002-2007, 2007-2012) spoke of SMART (simple, moral, accountable, responsive, and transparent) governance. However, the passing of the Right to Information Act in 2005 marked the beginning of the promotion of a culture of citizen-enforced accountability by the Indian government. The National Knowledge Commission, an advisory body constituted in 2005 by the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, made

two important recommendations relevant to implementing an open data initiative in India. This resulted in the facilitation of public-private partnerships in creating

five portals. While the recommendations did ask for all government departments to contribute to the process, the portals host data largely provided by NGOs, researchers and academic organisations.

In 2012, the Government of India formulated a policy known as the National Data Sharing and Accessibility Policy (NDSAP). The NDSAP promotes transparency, accountability and greater engagement of the public by providing them with access to unrestricted government data through a data portal (data.gov.in). Since its inception, the

portal boasts 29,387 resources available to download, 26,086 datasets, 101 contributing government departments, 112 chief data officers, and 2.96 million downloads from the website. Not only does the website host a variety of datasets across sectors, but it also has data visualisation tools for over 800 datasets.

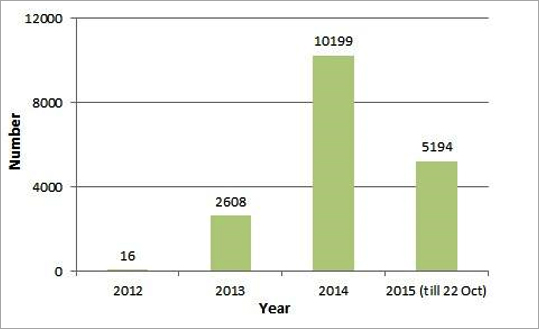

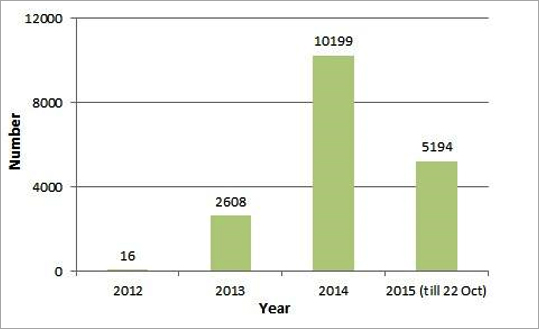

Figure 1: Growth of datasets during 2012 to 2015

Source: community.data.gov

Source: community.data.gov

According to an international

Open Data Index published by 'Open Knowledge Foundation', India ranks at #17 (of 122 countries in the index) in the 2015 rankings, tied with countries like Canada, Spain and Italy. However, due to the inclusion of new factors into the index and restrictions on licensing, India’s overall ranking has fallen from its 2014 ranking of #10. This fall from being 68 percent open to 55 percent open cannot be considered entirely accurate though. The index does not currently take into account health data, the inclusion of which could alter the ranking. Furthermore, as of July 2016, the government is making

efforts to change the license of the open data portal to an

'open government data use license.'

A closer look at open health data would reveal some interesting findings. There are 266 catalogues of health related data on the open data website and a majority of the healthcare data in India is public sector data. However, 70 percent of healthcare expenditure takes place in the private sector, calling into question the representativeness of health data. Health Management Information System (HMIS) data is a major source of health coverage indicators, but while the data is free to access, there are questions about its accuracy, and completeness.

Studies show irregularities in the generation of reports, in over-reporting outputs and outcomes, data inconsistencies, etc right from the sub-centres at the micro level up to the district and state numbers at the macro level. The private health sector needs to be incentivised to cooperate in sharing essential data that would help in policy framing and evaluation. This sharing of data also needs to take into account concerns of patient privacy.

Apart from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), the more prominent sources of health data like the Sample Registration System (SRS) and Civil Registration System (CRS) are unable to provide wealth, religion or caste based disaggregated data. The large national surveys are expensive and time consuming, but are needed as facility level data like HMIS does not have the level of disaggregation to help drive policymaking.

The

data gaps in health need to be tackled in order to effectively monitor India’s progress with respect to the SDGs as well as the soon-to-be-released national development agenda of the NITI Aayog. Availability, timeliness, coverage, disaggregation and comparability of data are issues that officials and experts in the sector are well aware of and are trying to amend.

Table 1 gives a systematic look into various health data sources in India. The National Sample Survey (NSS

) unit level data is paid and unavailable for digital download. Surveys that are available online require registration and subsequent permissions to download the datasets.

Timeliness of data release also needs rectifying. According to an article in the

World Health Organisation (WHO) Bulletin on national health surveys in India, the time between completion of data collection and availability of individual level data in the public domain varied from nine months to 22 months for the NFHS. The SRS, a major source of health data, releases findings with at least a year’s lag. The CRS is supposed to be a continuous registration system, but data is very often incomplete and unreliable, therefore no core statistic on health is compiled from CRS.

Quality of data comes into question when we look for district level estimates. Only the Census, District Level Household Survey (DLHS), Annual Health Survey (AHS) and NFHS IV have district level estimates. In terms of

overall coverage, only NSS, NFHS, India Human Development Survey (IHDS), and the Global Adult Tobacco Survey cover all states and union territories, while SRS has maternal mortality figures for 15 states and union territories.

Comparability between surveys and across time continues to be an issue. WHO conducted a

feasibility of trends assessment within and between NFHS, AHS and DLHS, and found that differences existed with respect to reference periods and reference groups for the three surveys. There were also inconsistencies between

target respondents in the NFHS and DLHS over time. This would make comparison of findings from these datasets across time and space much more difficult to interpret.

Way forward

In spite of efforts by the government to create an open data exchange, there is a lot that needs to be done. In terms of participation, while the data.gov.in website boasts of 101 government departments contributing to the portal, only 24 of them are state departments.

Only six states are represented by the 24 departments that contribute to the database. On Sikkim’s newly launched

web portal in June, only 20 out of 61 datasets relate to health and two catalogues provide district level estimates.

There needs to be a stronger movement pushing state departments all over the country to compile and publish data more promptly. The government needs to clarify the kind of data that state departments should be required to upload. To improve the quality of available health data, proper resources for the datasets also need to be provided. Codebooks with descriptions of variables and their indicators (like with the NFHS) should be available with the datasets to make understanding and using the data easier for researchers.

If the SDGs are to be achieved, issues of data quality, disaggregation, timeliness, openness, usability, privacy and funding need to be addressed. India needs to start counting the invisibles in health and the first step is through making data more open.

< lang="EN-GB">Table 1: Description of health data sources in India

| Data Source |

Periodicity |

Unit Level Data |

Geographical Disaggregation |

Open Data |

Registration |

Paid |

Coverage |

| Annual Health Survey (AHS) |

Annually, since 2010, now discontinued |

Yes |

District level estimates |

Yes |

No |

No |

EAG States |

| District Level Household Survey (DLHS) |

1998, 2002-04, 2007-08, 2013-14; now discontinued |

Yes |

District level estimates; rural/urban |

Yes |

No |

No |

DLHS-1,2,3 (All India) DLHS-4 (20 states) |

| National Family Health Survey (NFHS) |

1992-93, 1998-99, 2005-06, 2015-16 |

Yes |

State level estimates (NFHS I, II, III), District level estimates (NFHS IV); rural/urban |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

NFHS IV- all 29 States & UTs |

| National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) |

Regular rounds |

Yes |

National and State level estimates; rural/urban |

No |

— |

Yes |

All States & UTs |

| Sample Registration System (SRS) |

Annually, since 1970 |

No |

State level estimates for big states, recently, intra state regions and National Level; rural/urban |

— |

— |

— |

All States & UTs (Death rate, Birth rate, IMR) 15 States & UTs (MMR) |

| Million Deaths Study (MDS) |

Periodically, since 1999 |

No |

National level estimates |

— |

— |

— |

All States & UTs |

| Model Registration System (MRS)/ Survey of Causes of Death (SCD) |

Continuous registration; 1965-81, 1981-98 |

No |

National and state level estimates |

— |

— |

— |

Rural India |

| Civil Registration System (CRS) |

Annually, since 1969 |

No |

National and State level estimates; rural/urban |

— |

— |

— |

All States & UTs |

| Census of India |

Decennially, since 1951 (Independent India) |

No |

District level estimates; rural/urban |

— |

— |

— |

All States & UTs |

| India Human Development Survey |

2004-05, 2011-12 |

Yes |

State level estimates; rural/urban |

Yes |

No |

No |

All States & UTs |

| WHO SAGE |

2007-08, 2014-15 |

Yes |

State level estimates |

Yes |

No |

No |

Selected states |

| National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau |

Annually; now discontinued |

No |

State level estimates |

— |

— |

— |

10 States: Kerala, TN, Andhra, Karnataka, Gujarat, WB, MH, UP, MP and Odisha |

| Global Adult Tobacco Survey |

2009-10 |

Yes |

State level estimates; rural/urban |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

All States & UTs |

| Youth in India: Situation and Needs Study |

2006-07 |

Yes |

State level estimates; rural/urban |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu |

| Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) |

2010 (Pilot) |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Karnataka, Kerala, Punjab, and Rajasthan (Pilot) |

| Rapid Survey On Children (RSOC) |

2013-14 |

To be decided |

National and state level estimates |

No |

— |

— |

All States & UTs |

The author is a research intern at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

A major challenge faced in tracking progress across health and nutrition sectors is the unavailability of timely and quality data. In light of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as the national development agenda, India needs to boost its efforts. There needs to be an improvement in the volume, accessibility, variety and use of data, thereby making it easier for the common citizen to benefit from the open data initiative and ensure accountability. Progress has been made since 2012, but more can be done especially in the health sector to improve data collection and dissemination.

In 2011, 1.8 zettabytes (10^21) of digital data

A major challenge faced in tracking progress across health and nutrition sectors is the unavailability of timely and quality data. In light of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as well as the national development agenda, India needs to boost its efforts. There needs to be an improvement in the volume, accessibility, variety and use of data, thereby making it easier for the common citizen to benefit from the open data initiative and ensure accountability. Progress has been made since 2012, but more can be done especially in the health sector to improve data collection and dissemination.

In 2011, 1.8 zettabytes (10^21) of digital data  Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV