-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

These solutions have greater social and economic value than any other.

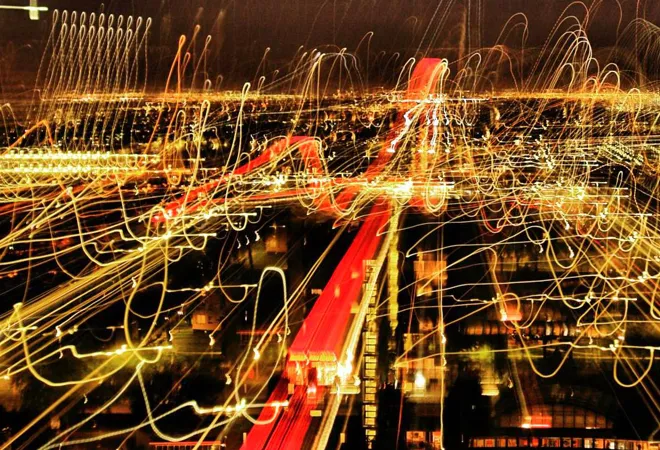

In the modern urban world, it would be difficult to locate a metropolitan city that does not have a traffic problem. Over a period of time, a whole series of words, related to traffic congestion, have gained currency to convey different degrees of the severity of the problem. Rush hour, traffic jam, crawling traffic, traffic snarl-up, motorway hold-up, town-centre bottleneck, bumper to bumper driving and gridlock are some of the terms that describe similar or different kinds of traffic scenario. Gridlock is the worst kind of traffic jam, where extraordinary long queues bring vehicle movement on an entire network to almost a complete stop for long periods of time. The worst gridlock reported in history is the Chinese traffic jam on Beijing-Zhangjiakou Highway. In Aug 2010, vehicles stood in a queue for eleven days. The queue ran for more than 100 km, with some drivers spending as much as five days at a stretch on the road.

Vehicle overload on city roads have several adverse fallouts — economic, environmental, personal and mechanical.

The larger the city, the more problematic city traffic seems to become. This is on account of the ever-rising number of motor vehicles on roads that outstrip the transportation infrastructure capacities of cities. Rising urbanisation brings more people into metros; economic success generates more income for families and this catalyses the purchase of more cars.

Vehicle overload on city roads have several adverse fallouts — economic, environmental, personal and mechanical. Lesser mobility results in larger investment of time in commuting and unfavourably affects the output of the working individual, besides increasing transportation cost of goods and services. These negatively influence both a city’s and an individual’s economic productivity. Besides, there are costs in missed opportunities. The environmental cost is reflected in larger air and noise pollution on account of greater use of horns and idling of vehicles. Personal consequences are seen to appear in the form of anxiety, psychological stress, road rage, heightened respiratory disease and spine-related problems. Vehicles themselves are not immune from impact due to additional stress imparted to vehicles through more wear and tear.

The environmental cost is reflected in larger air and noise pollution on account of greater use of horns and idling of vehicles. Personal consequences are seen to appear in the form of anxiety, psychological stress, road rage, heightened respiratory disease and spine-related problems.

Cities have tried out several kinds of antidotes to alleviate traffic congestion. Some of these fall in the realm of negative regulations, such as parking restrictions, high parking rates for longer parking, higher parking fee for larger cars and congestion pricing. Positive regulation includes reversible lanes to match asymmetric traffic demand, active traffic management through the use of GPS and mobile traffic guidance. Others are developmental via the addition of fresh traffic and transportation infrastructure. Quite clearly, none of these have the strength to singly eliminate traffic woes. Even considered together, their efficacy has been limited or short-lived. This has led to transportation planning rising up the ladder as a priority strategy. This invariably comprises these days the promotion of mixed land use and transect inputs that get fully integrated with land use planning as critical components. These strategies allow a city to be organised in a manner that would effectively reduce the need to use vehicles. This is because the arrangement allows most activities to be carried out within short distances either on foot or by cycle.

Infrastructure solutions attempted by cities include road-widening, single or multi-layered flyovers and under passes, grid separators, new roads, signaling systems, signal syncronisation, more parking lots and other intelligent traffic responses that use technology to offer solutions. Many transportation experts have been critical of infrastructure additions for personal transport. Road widening, for instance, has been criticised as it makes road crossing for a pedestrian difficult. Additional lanes to ease traffic have been compared to bulky men loosening their waist belt to accommodate accumulated obesity. They have also pointed out that these additional infrastructures come at tremendous cost. Many of these heavy engineering projects involve highly disruptive interventions that throw parts of a city into disarray, destroy fragile streetscape and work against other viable public transport options. Ultimately, they yield temporary results. The iron law of induced demand comes into play as more cars bring the city back to square one.

Since it is getting tellingly clear that any amount of traffic and transportation infrastructure additions would fail to provide very long-term solutions if citizens keep buying personal cars and commute in them on city roads. This has led to a universal agreement that cities must migrate from personalised vehicles to public transport systems. Many large cities have taken up the construction of metros; others have opted for a BRTS (Bus Rapid Transit System) on account of affordability and relative ease of construction of a dedicated lane for buses.

The iron law of induced demand comes into play as more cars bring the city back to square one.

What is significant to point out that transportation infrastructure comes at great cost. Given the current financial position of cities, one is constrained to conclude that cities would find it virtually impossible to add, operate and maintain these infrastructures for a substantial length of time. Many of these infrastructures would show signs of atrophy and would have to be replaced. At the same time, cities would have to invest in infrastructure for expanding areas and rising populations.

In the above cited background, it may be desirable to look at least-cost, non-infrastructure solutions to mounting traffic. These are inexpensive propositions and are not very difficult to implement. They primarily require the citizens and city decision-makers to sit together and work out solutions. A few of these are suggested in the following lines. These can be termed as social inputs to alleviate traffic congestion.

Households need to buy goods. An agreement could be reached among businesses whereby goods are increasingly delivered through home delivery services. This is already happening. But this could be organised in such a manner that both individual trips and delivery trips are minimised and there is no cut-throat competition to reach goods at lightning speed. Such one-upmanship offsets the gains of reduced individual car-trips by greater delivery van trips. It should be possible to rationalise distribution and deliveries by the use of consolidation and redistribution depots and the use of fewer vehicles for making the ‘last mile’ deliveries and collections in the city. Citizens may also agree that they would consciously attempt to reduce vehicular trips for other purposes by using technology. Socialising, meetings and similar activities can partly be done through the use of electronic media.

Peak traffic is a phenomenon that happens because organisations, offices, schools and colleges have more or less the same operating hours. It is possible that citizens and city decision-makers sit together and agree on staggering of operating hours.

Peak traffic is a phenomenon that happens because organisations, offices, schools and colleges have more or less the same operating hours. It is possible that citizens and city decision-makers sit together and agree on staggering of operating hours. This may lead to some inconvenience; but this inconvenience could be shared by all by agreeing to share the inconvenience in different months. They could also agree on staggering of weekly holidays to different week days for different organisations. Friends and neighbours can agree to do car-pooling wherever convenient and school buses and office buses can be increasingly used. The nature of certain works is such that these could be done on some week-days from homes, obviating the need to travel to office. In this regard the most productive combination could be found that could provide relief to the traffic problem.

There could be many more innovative ideas that fall in the realm of society regulating itself. These methods actually have greater social and economic value than any other. The piling of regulation mandated by public agencies in some form or the other increases costs of enforcement, and hits economic productivity. Self-imposed social regulation, on the other hand, has positive impacts and can work wonders in a city for traffic as well as social regeneration. Above all, the city and city government get this at virtually no infrastructure cost.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr. Ramanath Jha is Distinguished Fellow at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai. He works on urbanisation — urban sustainability, urban governance and urban planning. Dr. Jha belongs ...

Read More +