As per the World Bank’s Global Findex Report 2017, India has an unbanked population of 190 million (second to only China). Around 48 percent of bank accounts in India remain inactive. On the other hand, mobile phones are becoming increasingly ubiquitous. India also has one of the cheapest mobile data rates in the world. In conjunction, there is a strong case to be made for leveraging mobile banking systems in order to increase the quotient of financial inclusion in the country.

In addition to leapfrogging the hurdle of physical access to banks, mobile banking has numerous other benefits. To begin with, the mobile-banking model is more profitable and cost-effective than branch banking and the ‘Business Correspondent’ (BC) model. In India, the cost of transaction through branch banking is estimated to be between INR 70-75, while that of mobile banking is INR one or less. The 2017 Global Findex Report 2017 reveals that more than 50 percent of those unbanked and 66 percent of inactive account holders in India have a mobile phone. Although 90 percent of Indians are digitally illiterate, the increasing adoption and ease of use of mobile phones makes mobile banking an ideal mechanism to propagate financial inclusion as opposed to any other technology.

Low income individuals face a difficult choice between how much to spend and how much to save in a bank account. This dilemma is further worsened by unforeseen exigencies which diminishes incentives to save in a bank account. It is perhaps the raison d’etre of financial exclusion. Can mobile banking resolve this conflict between liquidity and savings? Consider the following hypothetical situation: suppose the Indian economy were to be completely digitised and all transactions were cashless. Typically, low income individuals operate in the informal economy which relies predominantly on cash. In our hypothetical scenario, we allow the informal sector to be significantly small so that low-income individuals earn their salary, make daily purchases and pay utility bills using their bank accounts. It would then make sense for the low-income segments to receive their earnings in the bank account and conduct the transactions through this account. In this scenario, the above mentioned conflict between liquidity and savings would cease to exist.

Low income individuals face a difficult choice between how much to spend and how much to save in a bank account. This dilemma is further worsened by unforeseen exigencies which diminishes incentives to save in a bank account. It is perhaps the raison d’etre of financial exclusion. Can mobile banking resolve this conflict between liquidity and savings?

Can this hypothetical scenario be translated into reality? The answer is a big ‘yes’. Withdrawals and deposits into bank accounts and other transactions can be done using the mobile phone. This model of financial inclusion emphasises the increments of cost-effectiveness, increased account use due to automatic deposit and withdrawal, and higher propensity to create savings. Further, it will generate a trail of records reflecting savings behaviour and regularity of making payments, which can be used by fin-tech players to assess credit worthiness. This will in turn help low-income individuals avail credit more easily, thus further enhancing financial inclusion.

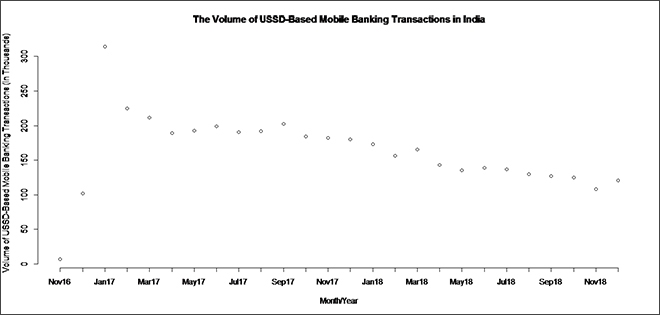

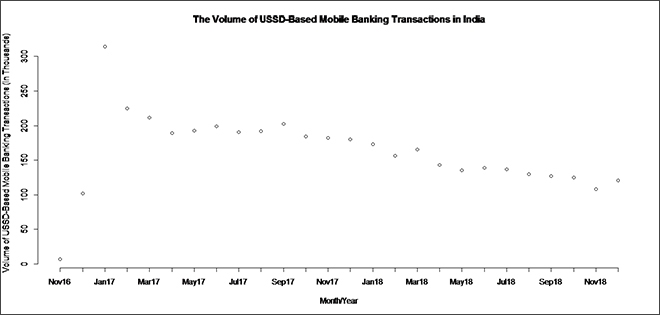

Of the many avenues of cashless transactions using mobile phones, the Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD)-based medium of cashless transactions — which can be conducted from any basic feature phone without the use of the internet — can be made useful for the low-income sections of society.

However, the USSD technology has certain limitations. First, a cost of INR 0.5 per transaction associated with the use of USSD levied by the mobile operator is enough reason to dissuade low-income individuals from using the service. Furthermore, once initiated, a USSD-based transaction cannot be cancelled. This exposes low-income individuals to the risk of monetary losses in case of erroneous transactions. The encryption protocol associated with USSD technology is quite weak compromising data security. Not surprisingly, the uptake of the USSD facility made available post demonetisation in India has not really picked up pace in the nation.

Source: NPCI

Source: NPCI

The demonetisation announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the ‘Cashless India’ campaign. The objective of this campaign was to launch India on the path of becoming a cashless economy.

A number of initiatives including exemption of service tax on digital transactions up to INR 2,000, asking banks to waive off charges on transactions up to INR 1,000 through IMPS, USSD and UPI etc. were introduced to subsidise costs associated with cashless transactions.

Yet, a crucial measure to boost cashless transactions would have been to waive off the mobile operator charges on USSD-based services. Given the scale of change that could be expected from this waiver from the MSME and informal sector in the medium term, the resources released from not having to print money can subsidise this waiver. The waiver could also be cross-subsidised by taxing the rich on banking and other financial transactions in a way that does not pinch hard.

The lack of digital and financial literacy hinders the ability of low-income individuals to understand the benefits of USSD-based mobile banking and make use of it.

Given that the websites of both the Cashless India campaign and the National Payments Council of India pitch USSD-based services as an instrument for universal financial inclusion, it is incumbent on the Government to initiate appropriate technological interventions to circumvent the encryption weaknesses of the USSD technology.

After the initial hype post-demonetisation, the drive to make India a cashless economy appears to have worn off. A lot could have been done to boost USSD-based mobile banking. The lack of digital and financial literacy hinders the ability of low-income individuals to understand the benefits of USSD-based mobile banking and make use of it. There is a need to study the psychological and behavioural hindrances that prevent the adoption of cashless transactions and tackle them with appropriate awareness campaigns, advertising and marketing strategies and digital and financial literacy training camps. Lastly, the Government’s stance on security and data privacy is extremely skewed in favour of weak encryption protocols, and more surveillance and interception. If the nation has to move further on its path towards becoming cashless, there is a need to tone down this approach and contemplate a robust encryption regime.

The demonetisation campaign has received scathing criticism. In order to demonstrate its positive potential, the ‘Cashless India’ campaign can be revived with universal financial inclusion as its primary goal and mobile banking its principal instrument.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: NPCI

Source: NPCI PREV

PREV