Millets for climate resilience and food security in India

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global temperatures will reach or even exceed 1.5 degrees of warming in the next two decades. Given the current trends of climate action, contingency policies that can ensure security from global warming need to be implemented. Global warming will not only have far-reaching impacts on water availability but will also simultaneously affect agriculture and food security. The agricultural sector, which consumes almost 89 percent of groundwater, needs to be moved in favour of practices that ensure nutritional and water security and entail the minimum social costs.

Certain cereal crops that are highly water-intensive occupy the greatest share of the market, imposing a trade-off between food security and water availability.

India is a highly water-scarce economy, accommodating 18 percent of the global population, with only 4 percent of the world’s water resources. Prolonged exploitation of groundwater resources has led to its depletion, highlighting the need for immediate adaptation policies to improve groundwater management. While programmes like the Atal Bhujal Yojana are necessary to increase efficiency in the management of groundwater, the need to reduce sectoral water consumption should also be emphasised. Certain cereal crops that are highly water-intensive occupy the greatest share of the market, imposing a trade-off between food security and water availability. The role of drier crops like millet in circumventing the food and water trade-off is discussed to highlight how Indian practices can be replicated on a global scale.

The shift away from millets in India

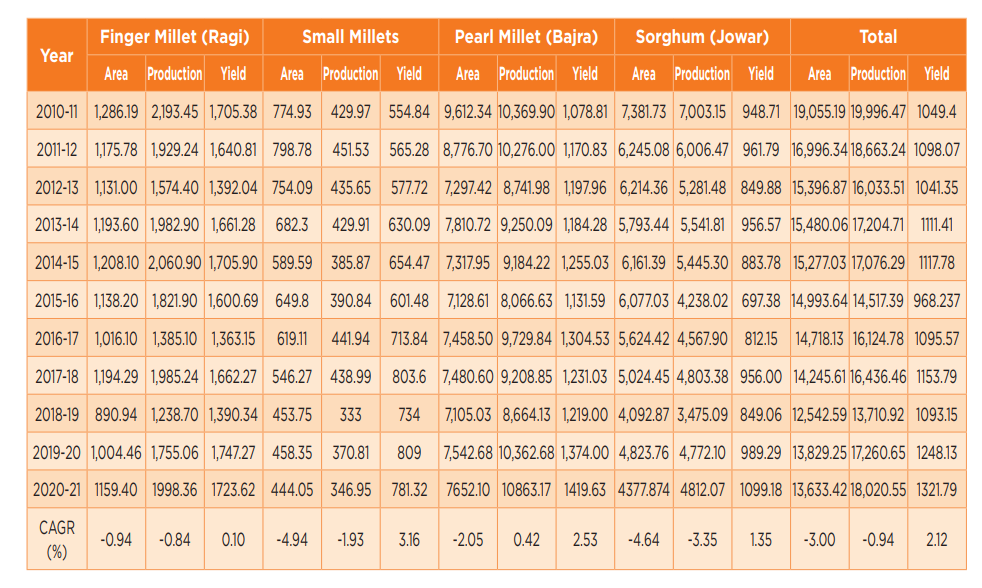

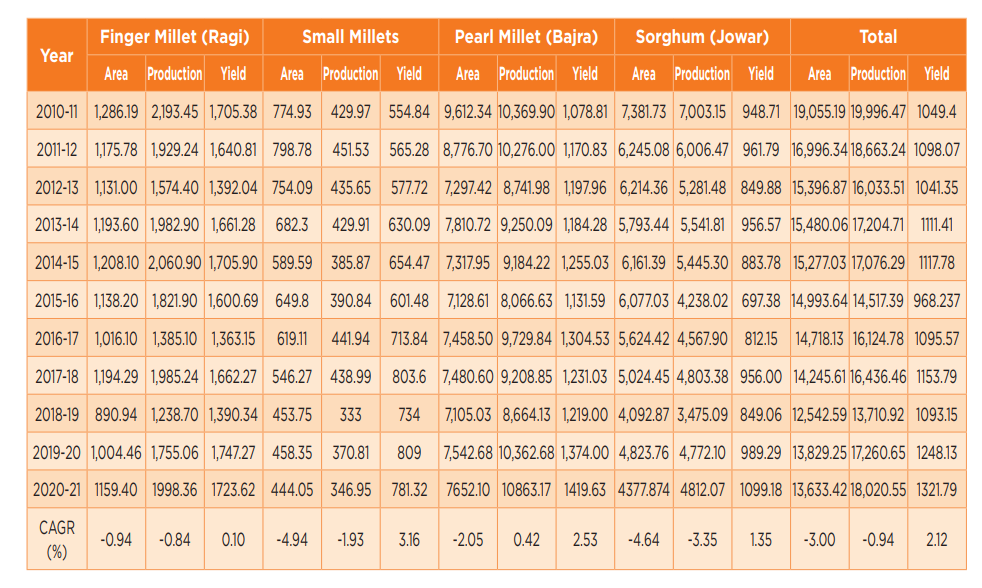

Rice, wheat, and sugarcane, which are the most water-reliant crops, comprise 90 percent of India’s crop produce. India is the largest exporter of rice, each kilogram of which consumes almost 3,500 litres of water, exponentially increasing its social cost of production. Rice is responsible for 10 percent of the global methane emissions and accounts for around 30 percent of the methane emissions in South-East Asia. Despite these, the rice- and wheat-promoting Green Revolution in India, has wiped out the presence of millets from farmers’ lands and consumers’ food bowls (Table 1).

The need to reintroduce millets as a staple cereal has been recognised in the face of rising temperatures and declining water reserves. The rainfall requirement of millets such as Sorghum (jowar), Pearl Millet (bajra), and Finger Millet (ragi) is less than 30 percent of that required for growing rice. While wheat cultivation is expected to become unpracticable with the projected rise in global temperatures, millets provide a sustainable alternative that can grow under drought and higher temperature conditions. It is also found that millets have 30 to 300 percent more nutritional content when compared to rice, ensuring that nutritional security will not be compromised with climate resilience.

Table 1: Area (in 1000 Hectare), Production (in 1000 tonnes), and Yield (in kg/hectare) of Millet Crops in India from 2010–11 to 2019-20

Source: NITI Aayog

Interventions in the Indian policy space

In 2011-12, the Initiative for Nutritional Security through Intensive Millets Production was launched to show the advanced technologies available for millets production and in turn, to also increase consumer demand. The National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture, focusing heavily on ‘Water Use Efficiency’ and ‘Nutrition Management’, promotes millets cultivation through various financial incentives to the farmers. The National Food Security Act (NFSA) introduced in 2013, directed the distribution of coarse grains but did not make any specific provisions for millets. Only jowar, bajra and ragi are procured by the government, leaving the minor millets without any production safety nets. However, later in 2018, millets were recognised as ‘Nutri Cereals’ and promoted under the National Food Security Mission, which led to the declaration of 2018 as the National Year of the Millets.

In 2021, India increased the procurement and distribution period from six months to 9 and 10 months for jowar and ragi, respectively. The government recognised that marketing millets to the urban community will not suffice to shift aggregate preference—that there is a need for a broader shift that can be achieved only through distribution schemes and procurement. Moreover, to realign international preferences and promote the farming of millets, there needs to be an international market to make the crops remunerative. India identified this need to endorse millets as the cereal of the future and its proposal led the United Nations to declare 2023 as the International Year of the Millets. Since 2021-22, under the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for food products undertaken by the Ministry of Food Processing Industries (MoFPI), the government has reserved INR 800 crores to stimulate the production of “Ready to Cook” millets-based products.

With a low Glycaemic Index, it is postulated that they can be instrumental in the prevention of diabetes as well as in controlling body weight and hypertension.

Consumers need to be familiarised with the nutritional superiority of millets to regenerate demand. Besides being gluten-free, millets are rich sources of iron, calcium, and zinc. With a low Glycaemic Index, it is postulated that they can be instrumental in the prevention of diabetes as well as in controlling body weight and hypertension. Moreover, the grain contains about 65 percent carbohydrates in the form of polysaccharides and dietary fibre, causing a lower occurrence of cardiovascular diseases among regular millets consumers. Compared to rice, it has a higher calcium content and greater iron content than both wheat and rice. This reiterates the fact that resource availability will not be enhanced at the cost of nutritional security.

Strengthening the Indian value chain

India is the largest producer and second-largest exporter of millets. Despite losing 56 percent of the acreage in the last 5 decades, millets production has gone up from 11.3 to 16.9 million tonnes due to increased productivity and improved technology. The replicable frameworks and policy-relevant know-how generated from the Indian endeavour to promote millets need to be highlighted.

Indian research over the last five decades has led to the innovation of over 80 and 200 improved cultivars at the national and state levels which have high grain yield as well as biotic and abiotic resistance. The new forage sorghum cultivars have shown higher digestibility, are cyanogen-safe and also minimise losses compared to previous cultivars. On the other hand, biofortified bajra has been developed as the solution to provide food, nutritional and economic security to marginalised farmers. Pearl millets are nutrient rich and climate resilient which makes it important for farmers in arid and semi-arid regions where the effects of climate change will be the highest.

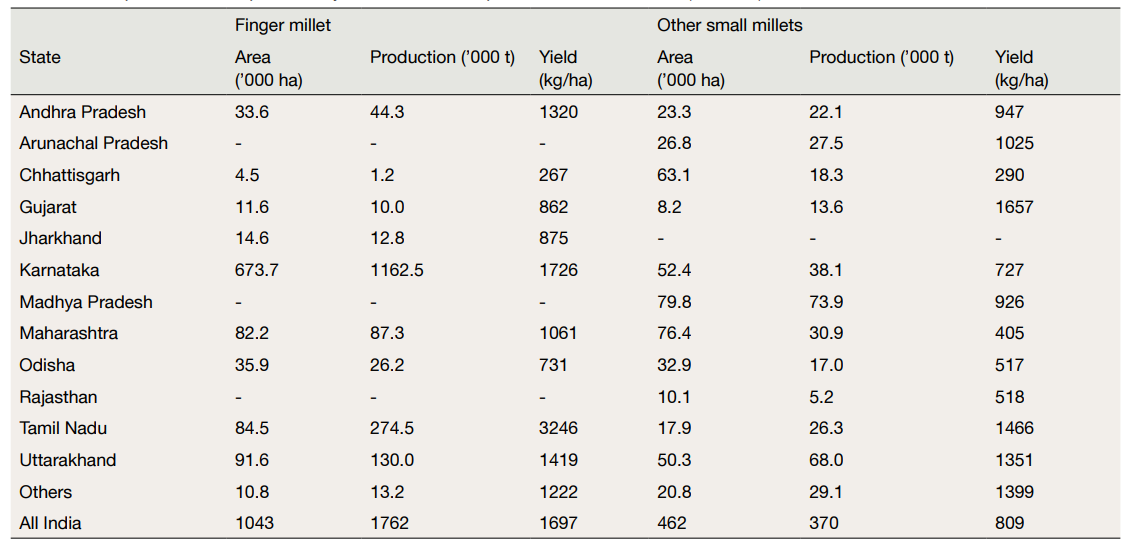

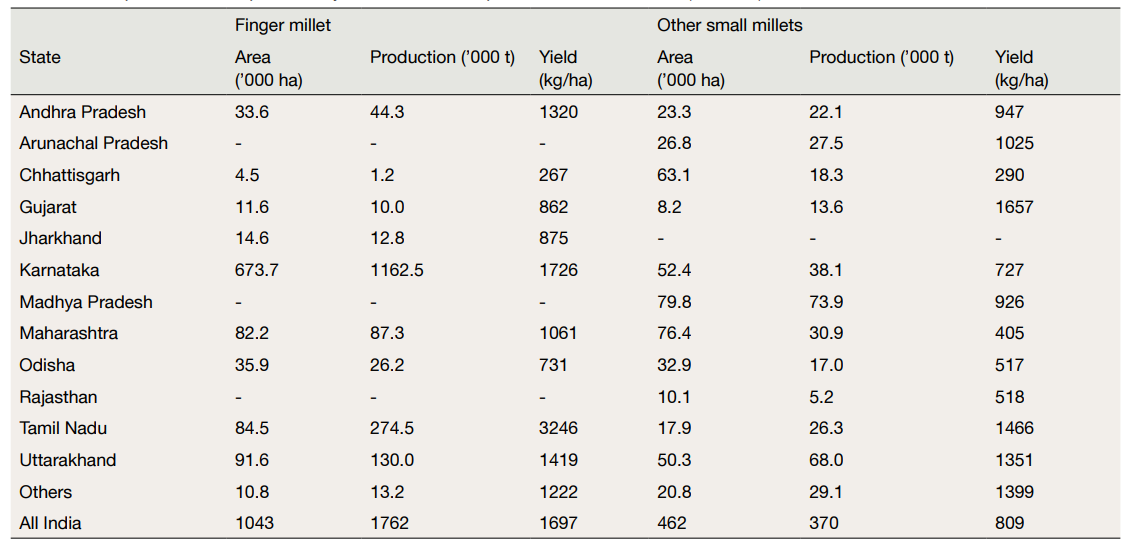

Table 2: Area, production, and productivity of small millets in prominent states of India (2019–20)

Source: Ministry of Agriculture

To exploit the full potential of pearl millets, quality inputs are necessary which can be ensured through standardised seed production technologies. Finger millet, little millet, kodo millet, foxtail millet, barnyard millet, proso millet, and browntop millet, which comprise the family of small millets in India, need to be brought under the ambit of procurement.

The imperatives

Millets provide an efficient solution to the current dilemma between food security and resource extraction. However, to scale up the millets industry, appropriate policies need to be designed before the markets can operate fully. Effective research to develop high-yield varieties of small millets is necessary as the farmers face a productivity issue that substantially reduces their profitability. Market interventions in the form of Minimum Support Price (MSP) and subsidies need to incentivise the production of the crops. The International Year of the Millets should be manoeuvred to shape global preferences and make them aware of both the nutritional and sustainability benefits of millets. Finally, the climate resilience attributes of millets should be emphasised to persuade international governments to increase global production and consumption of millets in an increasingly warmer world.

Arya Roy Bardhan is a Research Assistant with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV