-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the lives of many, directly and indirectly. In India, the pandemic cost us the lives of over 260,000 Indians directly, while many thousands were impacted by several parameters such as the lack of medical infrastructure, economic downturn, migrant crises, domestic violence, mental health disorders, amongst others. The somewhat less discussed impact of this pandemic is the deteriorating mental health; this has been a feature of almost all pandemics in history. The SARS outbreak in Asia in 2003 showed a spike in depression and anxiety symptoms in almost 50 percent of those who recovered. Similarly, the Ebola virus outbreak in Africa in 2013 stated that 47.2 percent of survivors were possibly depressed.

The halted health systems damaged supply chains and forced countries in their entirety to go into an absolute shutdown. A survey of 130 countries conducted by the World Health Organisation (WHO) concluded that 93 percent of the countries faced severe disruptions in their critical mental, neurological, and substance use services delivery and a heightened need for such services. Additionally, 67 percent suffered disruption in psychotherapy and counselling services and 30 percent lost access to regular medications for mental and neurological disorders.

Traditional triggers for mass anxiety in the population have been fear of infection, death, death of loved ones, loneliness, withdrawals, violence, co-morbidities, and more. But the new digital age has brought-forth additional triggers of psychological stress like social media, lack of digital skills, migration stress, financial insecurity, poor accessibility to digital tools and lost intimacies. Hence, the current climate of chronic stress presents us with tremendous new possibilities and indicators of the future of population health only if we choose to improve and adapt.

Traditional triggers for mass anxiety in the population have been fear of infection, death, death of loved ones, loneliness, withdrawals, violence, co-morbidities, and more. But the new digital age has brought-forth additional triggers of psychological stress like social media, lack of digital skills, migration stress, financial insecurity, poor accessibility to digital tools and lost intimacies

The second wave of COVID-19 has brought the healthcare sector to its knees with shortage of essential drugs leading to spurt in black market activities; inadequate and insufficient medical infrastructure; mismanagement of resources; and burnt-out doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals. April 2021 saw fear, panic, and chronic stress as a distressing feature of the population witnessing unprecedented spike in fatalities and record-breaking eruption of new cases. But it’s not just the past month, the past year of the pandemic brought forth a range of neurological disorders affecting mental well-being globally.

Since the onset of the viral pandemic, several scientific evidences came to light documenting its aggravating impact on the population’s overall well-being. According to a research study reported by Economic Times, 338 non-COVID deaths were reported in India within the first 45 days of the pandemic. Primary reasons cited were loneliness and fear of testing positive, deaths due to withdrawal symptoms caused most commonly by sudden shutdown of liquor shops, exhaustion, starvation, and financial distress. Similar media reports from Gujarat’s 108 emergency helpline showed more than 800 cases of self-inflicted injuries and 90 cases of suicides very early on into the lockdown, between April to July 2020. The BMC-Mpower 1 on 1 mental health helpline for Maharashtra received about 45,000 calls within the first two months of the pandemic. Of these, 82 percent of the callers complained of anxiety, isolation, uneasiness, and depression, while others stemmed from sleep irregularities and exacerbation of pre-existing mental health issues.

Moreover, frontline health workers and law enforcement agents experiencing prolonged exposure to trauma, grief and disturbing circumstances were diagnosed with new concerns such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), isolation, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), anger issues, and suicidal behaviour, amongst others. With the collective crises mounting, initial anecdotal evidence suggested a 70 percent increase in depression and a strong will to end their lives after they or their closed ones tested positive. The human touch and everyday socialisation which functioned as a daily buffer was lost during this time, resulting in these inflamed feelings. The aggravation was noticeably higher in already vulnerable groups like women, young children, people in conflict, caste-class minorities, etc., and the sudden shutdown of daily physical interactions worsened the already skewed and unequal access to coping mechanisms and services for mental health.

A disturbing rise in domestic violence, sexual abuse, doubled care-work and domestic duties, childcare, and financial scare increased the fatigue and stress exponentially. In a survey of the Indian population, 66 percent of women admitted to being more stressed during the pandemic lockdown as compared to only 34 percent men. The International Labour Organisation’s survey too confirmed an increased risk of anxiety among youth (15-29 years) claiming every second person in the group suffered from it globally. Chronic procrastination, stress, job insecurity, work for home, digital burnout, and poor digital connectedness are deplorably affecting young people.

Sadly, 40 percent of the population suffering from mental disorders in high-income countries never receive the necessary help. The number is steeper at 75-80 percent in middle-to-low-income countries. On an average, there is a gap of almost 11 years between the onset of symptoms and treatment.

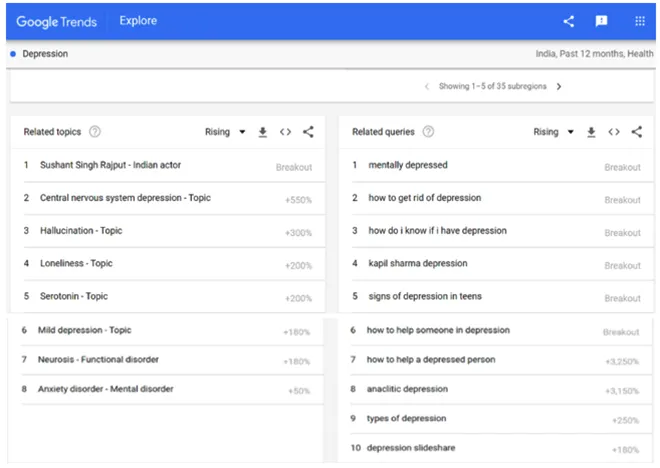

The year also led a sharp wave of exploration and enquiry on themes of mental well-being, which was triggered by the rumbling uncertainty among people looking to self-help and manage emotions. A simple Google Trends report on the term ‘depression’ in India yields the following top 10 related searches and queries in the past year (figure 1). The researched themes were depression, anxiety, its representations, and about Indian actor, Sushant Singh Rajput who allegedly committed suicide in June 2020. The phrases mentioned in the queries list with ‘breakout’ in the description indicates sudden, tremendous growth in the frequency of these searches. The list of searches demonstrates a growing need to diagnose depression and help a depressed person.

Figure 1 - List of highest searched topics/queries in the past 12 months in India related to the ‘Depression’

Source: Google Trends “Depression”

Source: Google Trends “Depression”Despite mass hysteria and loss, social trust emerged as a crucial factor affecting mortality globally. The World Happiness Report, 2021, presented that people with higher social and institutional trust were happier in comparison to people living in untrustworthy environments. This also led to consequentially lesser mortality rates among countries with higher mutual public trust. The report noted that quite contrary to other Asian and developing African countries, India, despite having raised its life expectancy has suffered an arrestive decline in well-being.

Owing to the protracted nature of these concerns, they annually cost a loss of almost US $1 trillion to the world economy. The World Bank has predicted that depression will put more burden on nations than any other disease in the next 10 years. Despite this, globally, countries dedicated a meagre ~2 percent of their health budget for mental health, prior to the pandemic. And while the Sustainable Development Goals Agenda for 2030 (adapted in 2015) aims to reduce pre-mature mortality by one-third by promoting mental well-being, the international development assistance for mental health continues to be less than 1 percent of all the assistance that is devoted to health.

India continues to be one of the most depressed countries in the world for several years now. In the absence of adequate assistance or the means to seek assistance, people have drifted to more harmful coping mechanisms like substance abuse, addiction and violence. The continued neglect of mental health has been repeatedly attributed to stigma and unawareness around it. A closer look also adds the outdated existing model of delivery and human resources in the country to the mix. As of 2019, the average number of physicians, doctors, and midwives per 10,000 population in India stands despairingly at 35.4. In continuation, the estimated number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population in India is a dreary 0.75 compared to 6 in high-income countries.

India continues to be one of the most depressed countries in the world for several years now. In the absence of adequate assistance or the means to seek assistance, people have drifted to more harmful coping mechanisms like substance abuse, addiction and violence

Additionally, counselling and associated preventative services continue to be vastly practiced in stigmatised institutions like psychiatry hospitals, disabling people to reach out. Instances of breach of privacy of the patient is, sadly, a fairly common reported problem as well. While the Mental Healthcare Act 2017 establishes a strict right to privacy, equality, and non-discrimination for its patients, without awareness and faith in the system, the stigma continues to grow antagonistically. Health insurance providers continue to avoid claims of medical services for mental and neurological disorders, making it an expensive line of dispensable services. The recent Shikha Nishcal vs National Insurance Company Limited (NICL) judgement is one such example where the Delhi High Court re-asserted Section 21(4) of the Act mandating NICL to cover the costs promised in the insurance policy.

Though last year was a painfully clear exposure of the deep crack lines in the exponentially growing need of holistic mental health services, the 2021 budget dedicated less than a percent (0.8 percent) of the total budget that was allocated to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) to mental health, i.e., 5.97 billion out of 712.69 billion. Despite being a country with more than 90 million people suffering with some guise of mental health disorders and the added burdens of COVID-19 pandemic, the 2021-22 budget designated a mere 400 million on the National Mental Health Programme. This implies that the Indian government will be spending about 1 US cent on an individual mental health patient in a year. With every third person with the SARS-CoV-2 infection developing depression, mood and anxiety disorders, dementia, and more psychiatric disorders, the resources are more strained and the system more taxed. On the other hand, only two major mental health institutions of the country, National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro-Sciences (NIMHNS), Bangalore and Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi Regional Institute of Mental Health, Tezpur received 93 percent of the entire mental health fund, i.e., 5 billion and 570 million respectively.

While the funding for these programmes has historically been bleak, the acute need to acknowledge and recover from the pandemic requires corporates, philanthropies and primarily governments to come together.

The world was not equipped to handle a pandemic of such an intensity, but it is worse prepared for a mental health epidemic. There is a dire need for focused, intersectoral efforts, and investments from stakeholders globally to combat this long-standing silent pandemic.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Mona is a Junior Fellow with the Health Initiative at Observer Research Foundation’s Delhi office. Her research expertise and interests lie broadly at the intersection ...

Read More +