This article is part of the series Colaba Edit 2021.

This article is part of the series Colaba Edit 2021.

It is now adequately established that the COVID-19 pandemic has adversely impacted all dimensions of human development in India, with dire consequences for the fulfilment of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Existing structural inequalities have been exacerbated since the start of the pandemic in early 2020, with severe implications for the most vulnerable populations—especially women and children. Amongst the various socio-economic inequities that have surfaced, health and nutrition issues amongst women, girls, and other diverse genders have been of concern. The disruption to public health and nutrition programmes, owing to a shift in State priorities and constrained mobility during the lockdown, has meant reduced access to critical services and worsening of physical and mental health and well-being of women and children. Against this background, this essay focuses on unpacking the Maharashtra State government’s health and nutrition budgets pertaining to women and girls. The state, as we know, has been at the epicentre of the pandemic in India. The article assesses the extent to which investments on health and nutrition are gender responsive, over a four-year period from FY 2018–19 to FY 2021–22.

Amongst the various socio-economic inequities that have surfaced, health and nutrition issues amongst women, girls, and other diverse genders have been of concern.

In understanding public healthcare through a gender lens, two aspects are considered: One, women and girls as beneficiaries of services; and the other, women as providers of services. As beneficiaries, three types of interventions that are critical to women and girls’ well-being are covered in this essay: Health services related to their reproductive role, health needs other than reproductive health (henceforth referred to as ‘other health needs’), and nutrition services. However, it may be clarified that owing to the paucity of sex-disaggregated beneficiary and budget data on other health needs from the Public Health Department and the Medical Education Department, the analysis on these aspects is limited. Further, while the public health systems do have a critical role to play in responding to gender-based violence, the focus of this essay is on core health and nutrition interventions of the government.

Gender budget analysis

The overall gender budget for health and nutrition in Maharashtra, as reported in Government of Maharashtra’s annual Gender Budget Statements (GBS) 2021–22 and 2020–21, is less than 1 percent of the State’s total budget for the respective years (Table 1). It may be noted that the gender budget across all sectors was 3 percent of the state’s total budget in FY 2021–22, of which 16 percent was allocated for health and nutrition. In FY 2021–22, INR 2,189 crore was allocated for the health and nutrition needs of women and girls, of which about 74 percent was on nutrition for pregnant and lactating women.

| Table 1: Overview of Maharashtra’s gender budget for health and nutrition |

| (Rs in crore) |

|

FY 2018-19

Actuals |

FY 2019-20

Actuals |

FY 2020-21

Revised Estimates |

FY 2021-22

Budget Estimates |

| Health |

465 |

662 |

700 |

769 |

| Nutrition |

1,813 |

2,172 |

2,182 |

1,420 |

| Total on health and nutrition |

2,278 |

2,834 |

2,882 |

2,189 |

| Spending on health and nutrition as a percentage of the state’s total budget |

0.75% |

0.75% |

0.66% |

0.45% |

| Source: Based on authors’ calculations from Government of Maharashtra’s Gender Budget Statements FY 2020-21, 2021-22 |

(1) Women and girls as beneficiaries of healthcare:

As mentioned earlier, for women and girls as beneficiaries of healthcare, three kinds of interventions covering reproductive needs, other health needs, and nutritional services have been analysed.

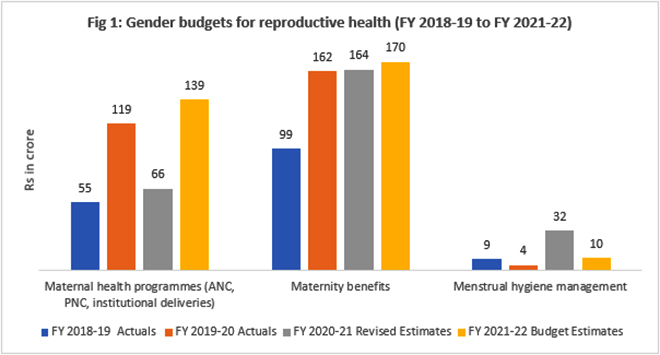

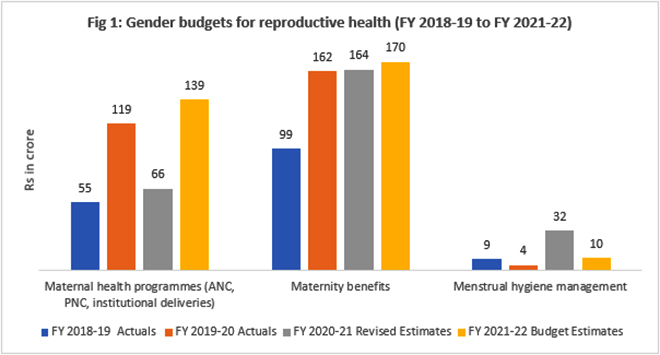

1.1. Budgets for reproductive needs

There are three kinds of interventions for reproductive health: Maternal health programmes, maternity benefits, and menstrual hygiene management (MHM). The budgets for maternal health services were INR 139 crore for FY 2021–22, which were much higher than the allocations for FY 2020-21 (INR 66 crore) and expenditures in FY 2019–20 (INR 119 crore) and FY 2018–19 (INR 55 crore) (Fig 1). In all, five interventions—Health check-up of pregnant women and newborns, Janani Suraksha Yojana, Janani-Shishu Suraksha Karyakram, Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan (PMSMA) and Maher Ghar—were reported for various aspects of antenatal and postnatal care, institutional deliveries, etc. Allocations for maternity benefits (Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana and Lapse Wages to ST women under the Human Development Mission) also observed an incremental rise to INR 170 crore in FY 2021–22 from INR 164 crore in FY 2020–21.

The utilisation for the maternity benefit interventions was 91 percent in FY 2019–20 and 79 percent in FY 2018–19. Two interventions were reported for MHM (Asmita Yojana for provision of sanitary pads and Promotion of MHM under the National Health Mission) with an allocation of INR 10 crore in FY 2021–22, which was a third of the budget in FY 2020–21. The total budgets for reproductive health in FY 2021-22 was 15 percent of the total gender budget for health and nutrition.

Allocations for maternity benefits (Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana and Lapse Wages to ST women under the Human Development Mission) also observed an incremental rise to INR 170 crore in FY 2021–22 from INR 164 crore in FY 2020–21.

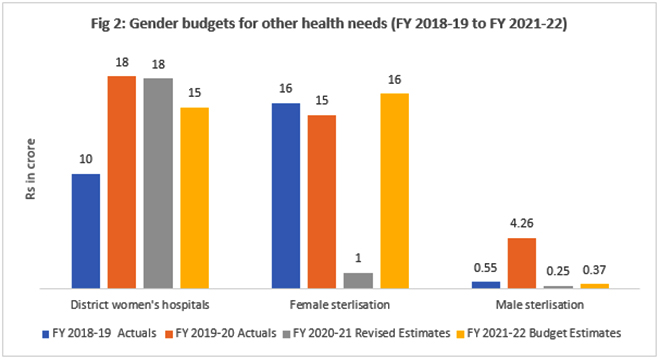

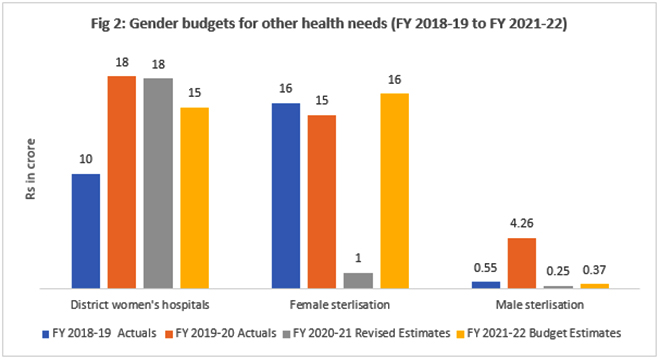

1.2. Budgets for other heath needs

Two types of interventions are reported in the GBS for other health needs: District women’s hospitals, and female and male sterilisations. District women’s hospitals had an allocation of INR 15 crore in FY 2021–22, which was less than the allocations and expenditure of INR 18 crore in FY 2020-21 and FY 2019-20 respectively. With regards to sterilisation, the gender imbalance is evident as the state continues to invest more on female sterilisation as compared to that for men (Fig 2). With an investment of 1.5 percent of the total gender budget for health and nutrition in FY 2021-22, other health needs of women and girls are clearly not prioritised by the State.

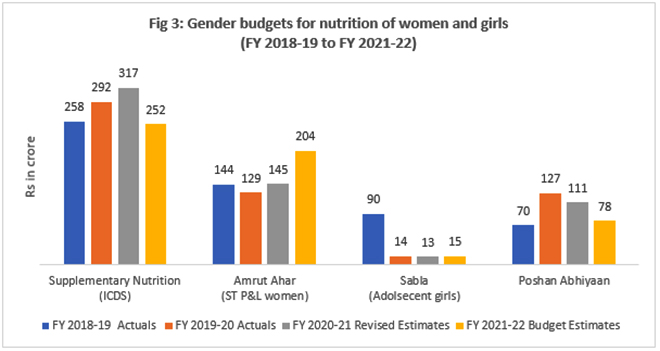

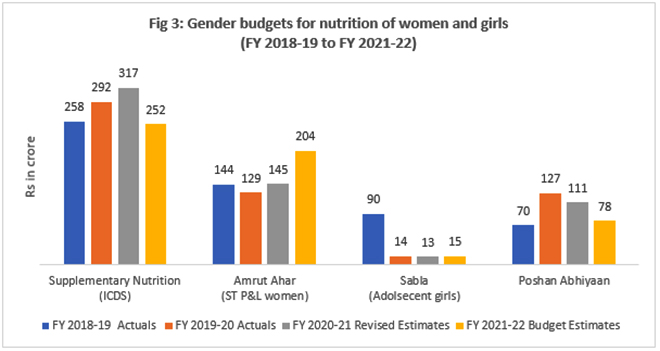

1.3. Budgets for nutrition

There are three nutrition schemes for women and girls: Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP) of Integrated Child Development Services, Amrut Ahar Yojana, and Sabla scheme for adolescent girls; and one intervention for building awareness around nutrition, i.e., Poshan Abhiyaan. For providing meals to pregnant and lactating women, an allocation of INR 252 crore was made in FY 2021–22 under SNP. This was much lower than the allocations in FY 2020–21, and expenditures of INR 292 crore in FY 2019–20 and INR 258 crore in FY 2018–19 (Fig 3). This is despite the high utilisation rate for SNP (84 percent in FY 2019–20 and 100 percent in FY 2018–19).

The Amrut Ahar scheme, which provides hot cooked meals to pregnant and lactating women in tribal areas, had an allocation of INR 204 crore for FY 2021–22, which was higher than the allocations for previous years. Sabla scheme for providing nutrition to adolescent girls has seen massive cuts in funding over the last three years. Allocations for Poshan Abhiyan too show a decreasing trend. The overall allocations for nutrition declined from INR 562 crore in FY 2018–19 to INR 549 crore in FY 2021–22, accounting for about a quarter of the total gender budget for health and nutrition.

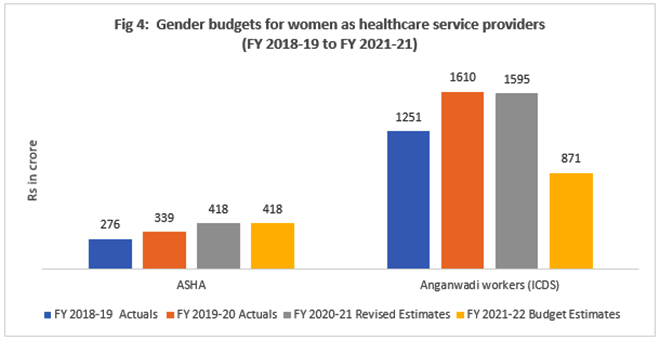

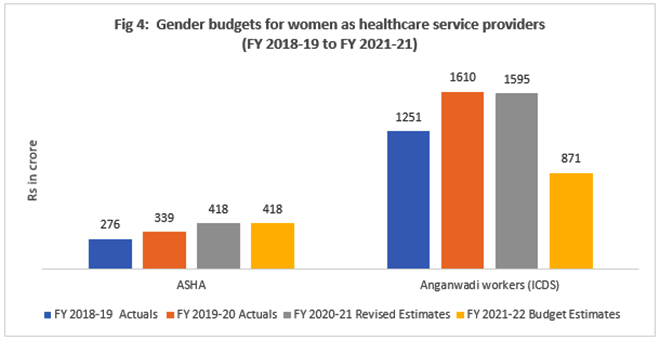

(2) Women as health service providers

Women constitute a majority of the frontline health workforce. Based on the data reported in the GBS, this analysis looks at the budgets for Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) for health-related interventions by the Public Health Department, and Anganwadis workers (AWW) who work with the Women and Child Development Department. There are about 67,000 ASHAs and 2 lakh AWWs in the state, who are paid a meagre honorarium that is inconsistent with the amount of work they do and the number of hours they spend working. The allocations for honorarium of ASHAs was INR 418 crore and for AWWs was INR 871 crore in FY 2021–22. The allocations for AWWs appear to have reduced in the current year, and this might see an addition in the supplementary budget, as has been done in previous years (Fig 4). The spending on honorariums of ASHAs and AWWs constitute about 60–70 percent of the gender budget for health and nutrition.

Key observations

As such, it may be said that the gender budgets for health and nutrition in Maharashtra are inadequate to address the existing and emerging needs of women and girls. Especially during the pandemic years, when there was a requirement for increased investments to address the added health vulnerabilities, our analysis shows a decline in gender budgets for health and nutrition (from INR 2,834 crore in FY 2019-20 to INR 2,189 crore in FY 2021-22) (Table 1). Moreover, many of these services were disrupted during the pandemic owing to closure of Anganwadi centres and Primary Healthcare Centres, adversely impacting ante and postnatal care for women.

No special allocations are reported for women’s mental health issues, despite evidence of them being more susceptible to depression and anxiety, especially due to the heightened triple burden during the pandemic.

Even within existing investments, there is clear lack of a gender transformative approach. The focus remains on the reproductive role of women and girls—more so, on the biological role of childbearing. All other aspects of physical health, such as the rising incidence of cervical and breast cancer, obesity, hypertension and diabetes, menopausal issues, and geriatric and palliative care, are poorly addressed. No special allocations are reported for women’s mental health issues, despite evidence of them being more susceptible to depression and anxiety, especially due to the heightened triple burden during the pandemic.

Further, needs of women from marginalised sections such as Adivasis, Dalits, the elderly, disabled, sex workers, transgender persons, and women from remote areas, hardly find any mention in the health and nutrition programmes of the government. Their accessibility, affordability, and availability to healthcare and nutrition facilities remain a challenge.

In view of the above, a needs-based approach to gender responsive planning and budgeting, which takes into consideration existing gender imbalances, is required. The road to recovery must include financing programmes that address basic health and nutrition needs, as well as gender transformative ones, to ensure overall well-being and empowerment of women, girls, and other diverse genders.

(Note: All graphs are based on authors’ calculations from the Govt of Maharashtra’s Gender Budget Statements FY 2020-21, FY 2021-22.)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV