-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

With Biden and IPEF highlighting economic transparency, it is seen as a way for Washington to create an Indo-Pacific trade bloc without creating a trading bloc.

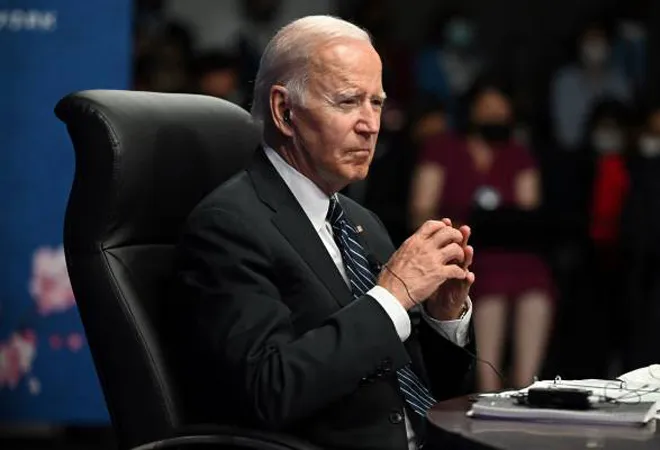

When President Biden took office in January 2021, his initial few calls signalled a key reset in both transatlantic relations and assuaging past tensions with North American neighbours, particularly with Mexico. Biden’s predecessor’s remarks with regards to trade and immigration had sullied ties with the southern neighbour.

As previously outlined, Biden’s outreach to North American and European heads of government was both focused on mending bruised wounds and broken fences and a concerted push towards trade, reassuring American allies that the US hiatus from the global engagement was merely an aberration and not a seminal moment of transition from the Washington doctrine.

Despite no initial calls to leaders in the ASEAN region or North Asia, President Biden like his previous boss was always focused on the Indo-Pacific.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was the Obama administration’s pivot to Asia, as a belligerent Beijing under President Xi Jinping began an assertive economic outreach to ASEAN nations and signs of military flashpoints in the South China Sea were starting to brew. The Chinese Sword of Damocles hung over the region as ASEAN centrality was put to test. Whilst the Trump administration had renamed the Asia Pacific as Indo-Pacific, the priorities for the region played second fiddle to President Trump’s overtly trade protectionist attitude, as the US retreated from trade deals such as the TPP However, President Trump by virtue of reneging on the TPP left a gaping American void in the region. Given Washington’s distress with Beijing proliferating economic and military heft in the region, many saw Trump’s withdrawal as akin to scoring an own goal or worse, perhaps allowing Beijing to win a match due to forfeit.

The IPEF is viewed not exactly as a course correction in place of the TPP but certainly, as a way to bolster American economic heft in the region.

The TPP now rechristened as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) went ahead, but just without Washington in it. Enter the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). The IPEF is viewed not exactly as a course correction in place of the TPP but certainly, as a way to bolster American economic heft in the region.

The Biden administration has prioritised the region, and within 18 months of taking office, there have been four principal level Quad meetings, including the inaugural in-person Quad Summit in Washington last September, followed by the second in-person Quad summit, held in Tokyo last month.

The IPEF, though not part of the Quad was launched by President Biden on his first presidential trip to Asia last month. The IPEF is not a trade pact, but trade is a salient component of the structure along with supply chain resilience, clean energy, decarbonisation, infrastructure, and taxation and anti-corruption issues.

Whilst China has alluded to the threat of the Quad as an Asian NATO, one that is bent on encirclement and hindrance to China’s strategic interests, the Quad, doesn’t metamorphosise into such a military group, despite joint-military exercises between the four. As previously argued, the AUKUS, a tri-lateral security pact with Australia, the US, and the United Kingdom, has overtly reprioritised the Quad’s focus on its economic and health incentives such as critical and emerging new technologies, supply chain resiliency, clean energy, infrastructure, vaccine diplomacy, and educational partnerships. There is synergy between IPEF and Quad members' priorities, given the convergence of issues and the mutual focus and importance on the region. But most importantly, both the Quad and IPEF want to help ensure the stability of free and open and rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific.

The AUKUS, a tri-lateral security pact with Australia, the US, and the United Kingdom, has overtly reprioritised the Quad’s focus on its economic and health incentives such as critical and emerging new technologies, supply chain resiliency, clean energy, infrastructure, vaccine diplomacy, and educational partnerships.

Last October, at the East Asia Summit, President Biden stated that the “United States will explore with partners the development of an Indo-Pacific economic framework that will define our shared objectives around trade facilitation, standards for the digital economy and technology, supply chain resiliency, decarbonization and clean energy, infrastructure, worker standards, and other areas of shared interest”.

Similar to the Quad, which first began in 2004 for Indian Ocean maritime relief post the tsunami, there is a sense of nebulousness on what the IPEF will shape up to be. But one thing it won’t be is a trade pact. For India, this is a welcomed caveat.

India’s aversion to trade pacts and overtly protectionist stances on trade has been the elephant in the room when it comes to India–US commercial ties. Whilst India has a comprehensive economic partnership with Japan, and has an early harvest deal with Australia, trade with the US has seen multiple layers of minutiae pertaining to market access from IT services to pork. Whilst the Trade Policy Forum in November 2021, has been a harbinger of positive trade to come through in terms of pork and mangoes, the barriers linger, causing former President Trump to once dub India as “tariff king”.

India walked away from the altar, just as others were committing to take their vows for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The elephant in the room was the dragon–China. New Delhi’s trepidation was that this trade bloc would give Beijing complete control over the biggest trading blocks in the region further hindering India. The other concern was the vulnerable domestic market for small and medium players that would soon lose out with the market at home being flooded with cheap Chinese imports.

The IPEF has been seen as a way for Washington to create an Indo-Pacific trade bloc without creating a trading bloc, that is without lowering trade barriers, ergo enticing Quad players like New Delhi.

Unlike the RCEP and the CPTPP, the IPEF is not a free trade agreement, but in lieu of the original TPP agreement, Washington needed strong economic heft in the region to placate Beijing’s economic dominance in the region. At times, the Quad has been seen as the best way to mention China, without mentioning China (in lieu of an open Indo-Pacific, rules-based international order, and shared democratic values between four countries). Similarly, the IPEF has been seen as a way for Washington to create an Indo-Pacific trade bloc without creating a trading bloc, that is without lowering trade barriers, ergo enticing Quad players like New Delhi.

Since the IPEF is not a traditional trade agreement, the 14 members so far are not obligated by all the four pillars despite being signatories. Especially on trade, the IPEF will not enforce market access commitments and reduction of tariffs, something that India and the US have sparred on.

Interestingly, the IPEF has all four Quad members, seven ASEAN members, South Korea, Fiji, and New Zealand. There is a great deal of overlap with the RCEP, which includes all the members of IPEF, save for India and the US and has China, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, all four of whom are not part of IPEF. Comparing the two would be comparing chalk and cheese, since they aren’t trading blocs, but they have a Washington–Beijing element of competition for regional economic dominance.

ASEAN centrality at test once again. Since the imbroglio of the South China Sea, ASEAN powers in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, and Vietnam, whose navies were in the crosshairs with the Chinese militaristic expansion in the Spratlys and Paracels islands had severe umbrage with Beijing. The reticence came largely from Thailand, whose adroit statecraft from days of yore have precluded colonial forces from taking reigns. Thailand doesn’t view China as a threat to the region and Bangkok’s concerns vis-à-vis Beijing, aren’t similar to that of Washington.

Also in the fray, have been Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, more invested in Beijing’s economic policy, and geopolitical gratitude for Beijing’s literal investments in their emerging economies.

The IPEF like the Quad seeks to home in on the digital economy, given China’s artificial intelligence (AI) prowess. The partnership seeks to rebuild supply chains disrupted by the pandemic and focus on climate action, as China triples its solar investments.

What Biden and the IPEF seek to highlight is the amorphous structure of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investment practices and outline some of the debt-trap diplomacies that have ensued as a result of reliance on Beijing’s coffers, case in point Hambantota in Sri Lanka. The IPEF is prioritising economic transparency instead.

The IPEF like the Quad seeks to home in on the digital economy, given China’s artificial intelligence (AI) prowess. The partnership seeks to rebuild supply chains disrupted by the pandemic and focus on climate action, as China triples its solar investments. The other fiscal priorities include financial transparency by helping emerging markets in the region track financial crimes in the form of predatory investments, money laundering and tax evasion.

For Washington, its relationship with New Delhi is an anomaly, given the depth of the strategic partnership, from a nuclear deal to military cooperation, instead of a treaty alliance. But Washington realises that the etymology of the region (Indo-Pacific) means India, and if the US sees its interests in the region threatened, it can only empathise with India, the only Quad member with a disputed land border with China.

A few years ago, a leading Indian diplomat mentioned that BRICS without India makes it look like a pact targeting the US (with Russia and China) and the Quad without India makes it look anti-China (given the US heft). India was the placating butter to simmer down the caustic spice of the geopolitical pacts.

However, the events of Galwan in 2020 have changed India’s reticence, particularly when it comes to helping lift the proverbial Greek Sword of Damocles, right now etched with Chinese characteristics all over it, from a region that New Delhi deems sacrosanct.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Akshobh Giridharadas was a Visiting Fellow based out of Washington DC. A journalist by profession Akshobh Giridharadas was based out of Singapore as a reporter ...

Read More +