Immediate burden of COVID19 lockdown in India, like in other developing countries, falls on the informal sector and its workers. Despite quite a few showing genuine concerns, the extent of the impact on informal sector workers is yet to be quantified. This essay projects estimated impact on this crucial beleaguered sector of Indian economy. COVID-19 is taking human lives every day, but a prolonged economic lockdown may endanger livelihood and survival of Indian informal workers in next few months; make no mistake about it.

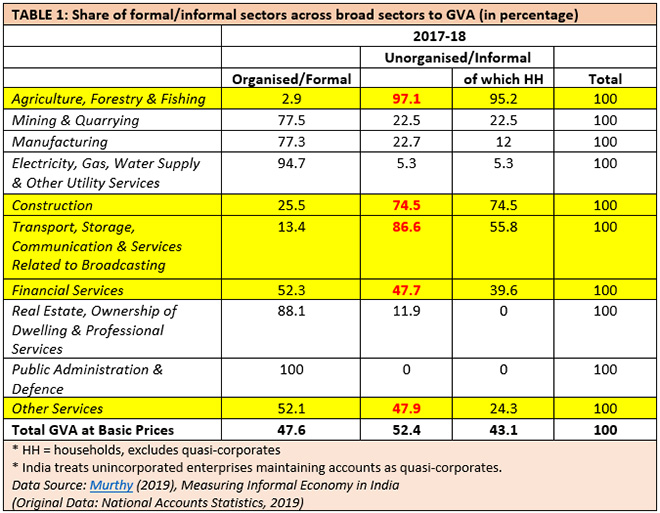

At the beginning of this year while introducing a bill to create a national database of informal workers in the parliament the government mentioned that roughly 90% of the country’s workforce is in various informal sectors. There are other estimates projecting the number at 81% of workforce, but the overwhelming informal nature of the economy is undeniable. In this essay, however, the National Accounts Statistics data is used and around 52% prevalence of informality in workforce is assumed. This caveat needs to be noted to understand the conservative nature of the projected impact, as described in this essay.

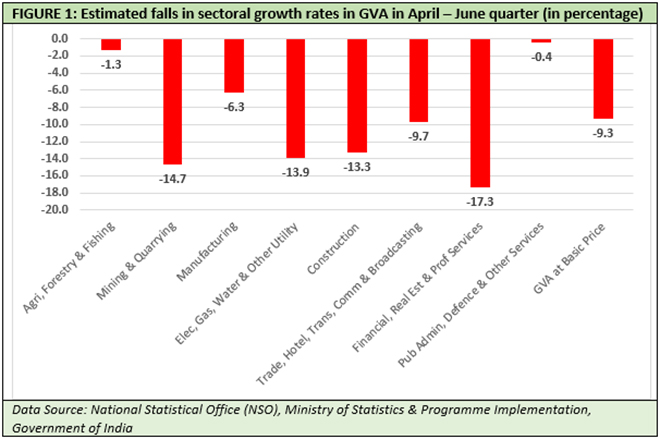

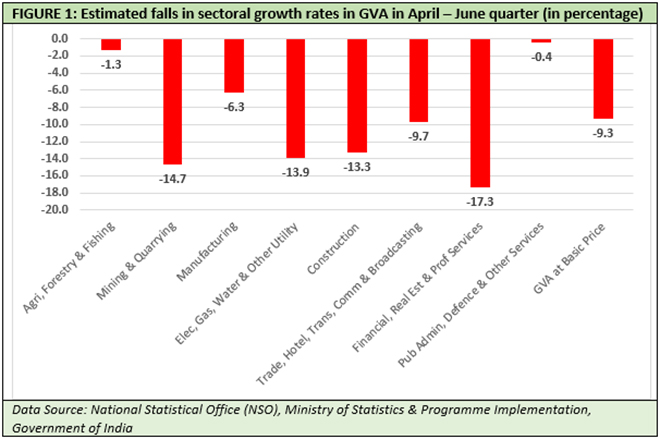

Assuming a -9.3% impact on national output (as projected by The Economist Intelligence Unit), following are the probable calculated impact on broad sectors of the economy (Figure 1).

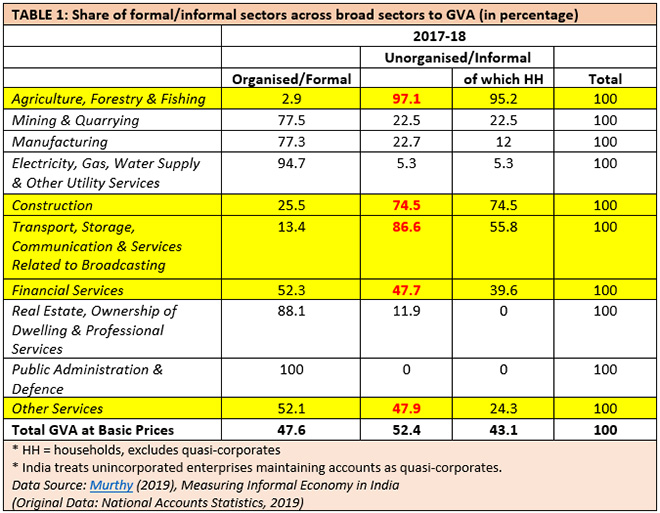

Table 1 provides the spread and composition of informal workers across these broad sectors. Around 52.4% of total workers in India are in informal sectors. Agriculture, forestry & fishing proportionally employs the most at 97.1%, followed by transport, storage, communication & broadcasting sector (86.6%), construction (74.5%), other services (47.9%), and financial services (47.7%).

According to the World Bank data, Indian workforce size has been 494,261,397 in 2019, and 52.4% of that will be 258,992,972. So, lockdown has affected close to 26 crore informal sector workers.

Though negative impact on agriculture is relatively less (Figure 1), informal nature of almost entire workforce related to agriculture, forestry & fishing makes this sector extremely vulnerable. The fact that around 70.7% of Indian population still resides in rural areas (PLFS 2017-18) makes the problem more complicated.

Construction, transport, storage and other informal services sectors are segments which need immediate attention. Proportionally more informal workers’ presence makes these sectors extra-sensitive to a prolonged economic lockdown.

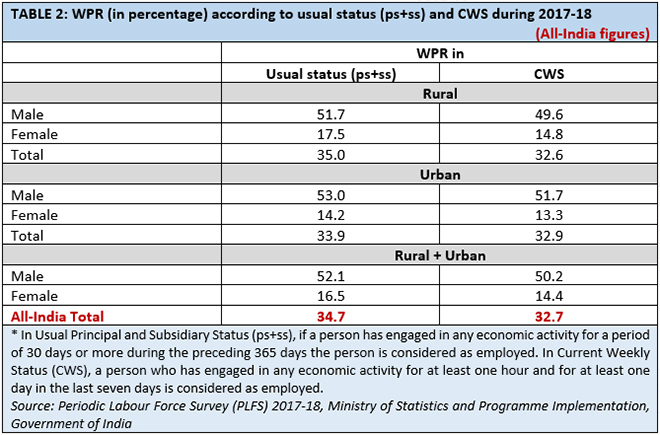

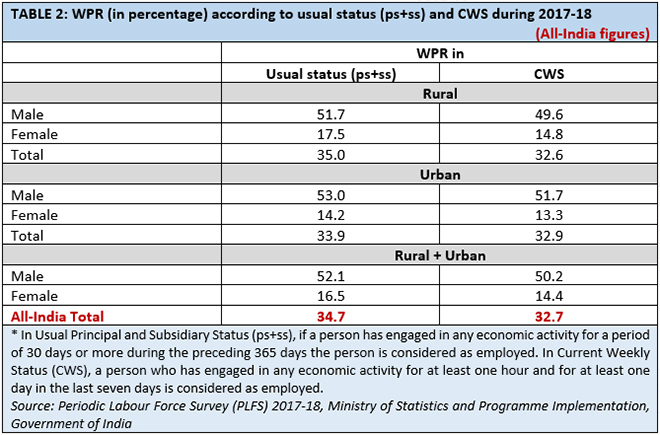

If we look at the Worker Population Ratio (WPR) – percentage of persons employed among the total population – then the dependence of other people on such informal workers becomes clear (Table 2).

All-India average shows that roughly one-third of population (around 33%) are engaged into some kind of work periodically. What it approximately means is that the rest two-third are dependent on these workers; or in other words – one worker losing employment opportunity implies grave survival danger for two more dependent persons.

Let us make a conservative estimate that around half or 50% of existing 26 crore informal workers are affected by this lockdown. Then the number of affected workers will be around 13 crore, and affected dependent persons around 26 crore more. Therefore, even in a conservative estimate around 39 crore people in the total population are under survival threat currently.

Informal workers are also there in the regular wage/salary segment. Let us hope that the appeal made by the Prime Minister to their employers not to sack them is working and assume that largely this segment of the workers is not in immediate danger. However, the casual labours in urban and rural areas are visibly under fire.

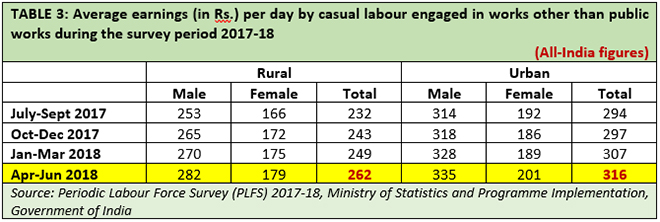

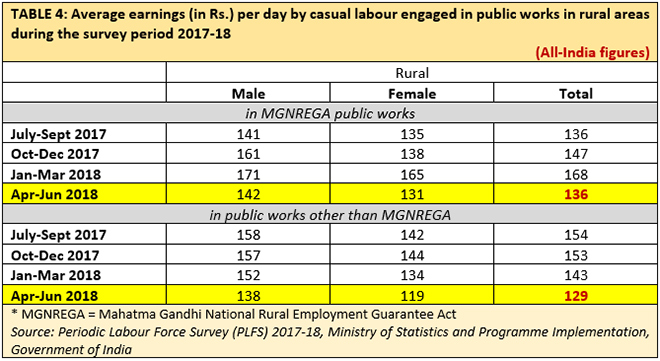

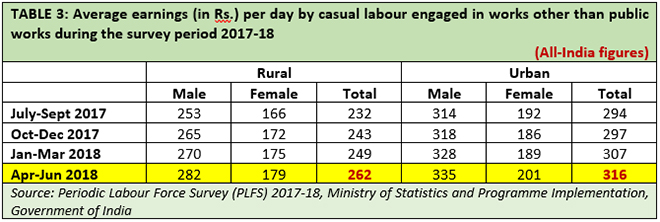

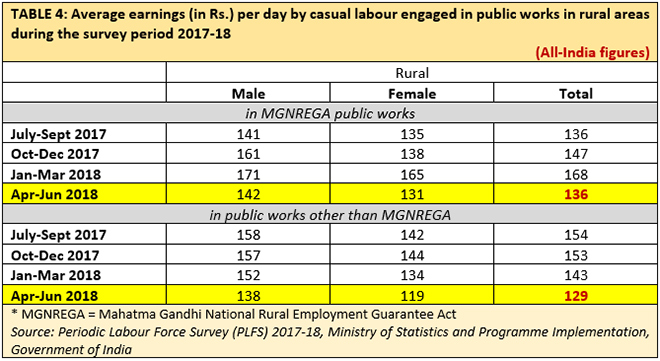

Table 3 and Table 4 are showing the meagre amount of daily wages these workers get. During the survey period of 2017-18, casual labours got daily wage of Rs. 262 in rural area and Rs. 316 in urban area for non-public works; in rural area they received average daily wages of Rs. 136 in MGNREGA public works and Rs. 129 in non-MGNREGA public works. Let us take an average of these four wage rates, which equals to Rs. 210.75.

Further, let us assume these workers worked for 25 days a month before lockdown and their total joblessness will extend to two months. So, in this period wage loss of each of these workers will be Rs. 10,537.50. In the prevailing absence of social security and job guarantee, this will translate into mass starvation (and may be death) for these workers.

If we go by our conservative estimate of 13 crore such affected workers then the minimum relief package should be worth around Rs. 1.37 lakh crore, or Rs. 1.37 trillion. If affected workers number goes up to (say) 20 crore then the relief package has to be Rs. 2.10 lakh crore, or Rs. 2.10 trillion. If these estimated numbers are averaged out, then the size of the relief package for India’s informal workers has to be at least Rs. 1.50 lakh crore or Rs. 1.50 trillion. Needless to say, whatever relief has been announced till now are too little, too less.

As the main demand is food for these workers, surplus food stock (way above the buffer requirements) with Food Corporation of India and other government agencies ideally should be a part of this overall relief package. Food should be given free to those in dire need through all avenues, including a temporarily universalised PDS (public distribution system). Most unfortunately, the government has decided to convert surplus rice to ethanol and finally alcohol-based sanitiser. When crores are spending days without food, this is shocking – to say the least.

Harvesting of existing crop in the field and sowing for coming monsoon season need migrant labourers. Immediate coordination between centre and state is needed for movement of willing agricultural migrant workers across and within states. Delay in this may result into further collapse of the basic food supply chain of the economy.

For a medium-term perspective, re-starting the MGNREGA is a welcome step. But, given the spread of the pandemic it might be wiser to make an attempt to build small health centres fitted with five or ten-bed facilities in rural areas utilising MGNREGA framework. That would bring some relief to the inadequate overstretched healthcare sector, and also would inject some demand in the rural economic system.

Urban marginal population, however, remains largely uncovered and vulnerable. COVID-19 has propelled the home delivery segment, and incorporation of a part of the informal workforce can augment the effort to provide relief. Home delivery of luxury and sin goods (wherever possible) can also be started with an additional charge. This can create temporary livelihood opportunities and ease the supply chain.

Lockdown can delay, but not stop the spread of COVID-19. Meanwhile, an informal economy like India may be in the dumps by the end of the year unless some innovative out-of-the-box decisions are taken immediately to reboot the economy.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV