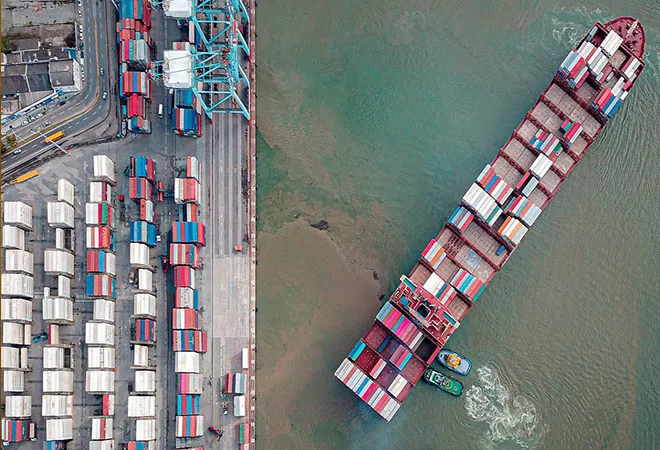

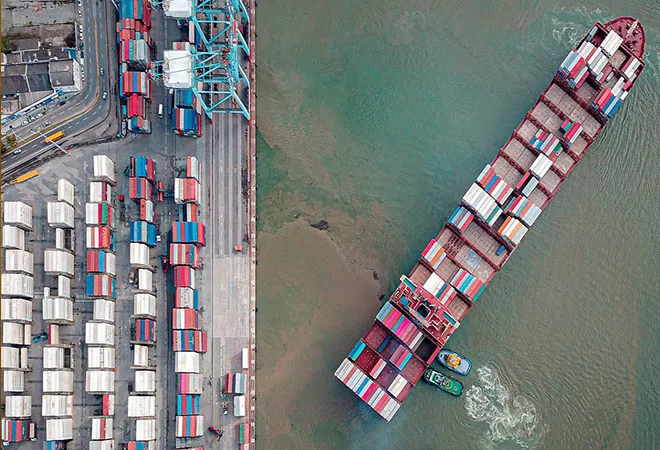

After eight years of negotiation, 15 Asian-Pacific economies including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand and ten members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) concluded the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement during a virtual signing ceremony on the occasion of the 37th ASEAN Summit in Hanoi, Vietnam, on 15 November 2020. This agreement covers almost a third of the world’s population — two billion people — and nearly a third of the global GDP — 28.9 percent. The negotiations concerning RCEP included trade in goods, services and investment; intellectual property rights; and special and differential treatment to less developed ASEAN member states, among others. The agreement will simplify the customs procedure and rules of origin laws between countries — implying reduced potential regulatory frictions for firms and countries for regional supply chains. Previously, a product made in Vietnam that contains Chinese parts, for example, might have faced higher tariffs elsewhere in the ASEAN free trade zone. Inclusion of a common set of rules of origin among the RCEP member countries will facilitate the easier movement of goods across the region and encourage these countries to look within the region for suppliers.

< style="color: #00699b">The agreement will simplify the customs procedure and rules of origin laws between countries — implying reduced potential regulatory frictions for firms and countries for regional supply chains.

However, issues about the environment and labour, which are being seen as necessary and key components of trade and policymaking in the post-pandemic world order, have been overlooked in the agreement. In light of Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, economists touted the RCEP as the world’s largest trade bloc for effectively consolidating the Asian market. The remaining countries of the TPP picked up the threads to form the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP); but once the RCEP agreement becomes effective, it would become the world’s largest export supplier and second-largest import destination.

India was a major part of the negotiations and agreed to the guiding principles of the RCEP up until November 2019. The fallout from these negotiations was the result of a number of economic and geopolitical reasons. Analysts have argued that India’s final decision to not sign the RCEP was ostensibly driven by the ongoing tensions with China. There was a fear among Indian policymakers that the elimination of tariffs would open the markets to a flood of imports, which will make India a dumping ground for cheap imports, predominantly from China, and hurt the local producers. While the defensive viewpoint of the Indian government appears to be befitting at the moment, Japan and Australia’s decision to go ahead with the RCEP despite ongoing geopolitical tensions with China should serve as a narrative for Indian policymakers to review their decision. By not signing the RCEP, India let go of a chance to become part of a mega-national trade deal that has the potential to shape regional trade patterns and economic integration in the future. RCEP member countries have left the door open for India to reconsider, with Japan and Indonesia insisting India join the trade pact in order to neutralise the economic clout preponderated by China.

Reasons for India backing out

As mentioned before, there were a number of economic and geopolitical reasons that pushed India to stay out of this trade pact, including prevailing trade deficits with a majority of the RCEP member countries, disagreement on demands put forth by India to the RCEP, and a Sino-centric effect influencing India’s decision to not sign.

< style="color: #00699b">Indian exports have become more competitive on the global scale in the past two decades, but FTAs have ensured a higher rise in imports in comparison to exports.

Trade agreements are generally formed in order to provide mutual economic benefits to the involved parties. In the case of India, evidence shows that Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) have resulted in unfavourable gains to other partners, which has worsened India’s trade balance. Indian exports have become more competitive on the global scale in the past two decades, but FTAs have ensured a higher rise in imports in comparison to exports. Currently, India has 14 Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) in force with a dozen more under negotiation; findings from NITI Aayog’s report on India’s performance in FTAs highlighted that total exports to FTA countries have not outperformed total exports to rest of the world. More specifically, FTAs with ASEAN, South Korea and Japan in the past have all instigated the trade deficit to increase significantly. For the fiscal year 2019, India registered a trade deficit with 11 RCEP member countries, signifying that trade pacts are not only about gaining access to markets in other countries but also giving market access to the trade partners. Given India’s poor performance in FTAs and inability to negotiate a balanced trade deal in the past, Indian policymakers were wary of a worsening trade deficit, which could have resulted post-RCEP.

Taking into account the prevailing trade deficits with a majority of the RCEP member countries and a lackluster performance by the domestic manufacturing sector, India proposed a three-tier approach for tariff reduction to the member countries. With ASEAN, India planned to reduce tariffs at 80 percent of tariff lines; for countries that already have an FTA with India — Japan and South Korea — India proposed a relief at 65 percent of tariff lines; and in the absence of existing trade agreements with countries like China, Australia and New Zealand, a provision of 42.5 percent of tariff lines was announced. However, the RCEP member countries required a greater reduction in tariff lines — aiming at 90% — and this proposal from India was neglected by the member countries.

< style="color: #00699b">China’s ambitious plan to become the next economic superpower was visible from the pressure it was putting on member countries to conclude the RCEP at the earliest.

In order to protect the domestic industries from a continuous surge in cheaper imports, during the 2019 negotiations in Bangkok, India proposed an inclusion of auto-trigger and snapback measures. In the event of imports crossing a specific threshold limit, these measures would be automatically triggered towards the partner country to contain any damage to the Indian economy. This was primarily aimed at China for manufacturing imports, but was also applicable in the case of Australia and New Zealand for their dairy products, and ASEAN for plantation products. But no agreement was reached in this regard.

China’s ambitious plan to become the next economic superpower was visible from the pressure it was putting on member countries to conclude the RCEP at the earliest. Without any trade agreement, India’s trade with China is already very skewed due to the presence of a robust manufacturing capacity in most of the sectors. Out of India’s total trade deficit, half of it is with China. As a result, India, without first solving the outstanding domestic concerns and enhancing infrastructure facilities, did not want China to invade the domestic markets. China’s success would have implied a worsening of India’s existing trade deficit. Finally, hollow provisions related to trade in services, where India has a comparative advantage, as opposed to the manufacturing sector and pressure from the interest groups in the steel and agricultural sectors steered the Indian government to opt out of the RCEP.

Why India should have signed

Apart from the shortcomings, India should have signed the RCEP to be able to influence the institutional policies of regional trade, which will shape the future of regional trade even if it meant accepting certain costs in the short-term. Being a member of RCEP would have kept India at par with the regional and global value chains and given it the opportunity to strengthen economic growth through an established trading system. Even during the waves of nationalism and protectionism in the world, the East Asian economies have been dynamic and continue to believe in trading through preferential routes and engagement in mega-regional agreements. Due to the presence of robust production and supply chains in Northeast and Southeast Asian countries, the regional value chains among the RCEP members is expected to be very close-knit. With the inclusion of India and further reduction in trade and non-trade barriers, the economic integration would have been deeper in the region — benefitting all the member countries. Other than the economic perspective, signing the RCEP comes with political and geopolitical value attached to it. This would have signaled India’s commitment towards trade liberalisation and regional integration in the midst of the pandemic.

< style="color: #00699b">Even during the waves of nationalism and protectionism in the world, the East Asian economies have been dynamic and continue to believe in trading through preferential routes and engagement in mega-regional agreements.

Undeniably, it is understood that when existing agreements are worsening one’s trade balance, it is difficult to sign another agreement with the same parties involved. But in an economically interdependent world, a conventional approach towards trade policy will most likely not work in favour of India. The ‘Make in India’ programme was launched with the motive to enhance the capabilities of the manufacturing sector. In reality, the manufacturing sector has instead contracted in the last few years. Let us assume if GDP in 2021-22 can reach pre-pandemic levels (2019-2020 GDP), i.e., INR 204 lakh crores; and further assume that the economy grow at least by 6% p.a. For the manufacturing sector to reach 25% of GDP by 2030, it would require the sector to grow in excess of 14% over the coming years. This is beyond what Indian manufacturing has ever achieved before. Import substitution can also play a significant role in this direction. But even if we consider 10 percent of merchandise imports (INR 3.4 lakh crore) to be substituted with Made in India products over the same time period, it would be relatively small to enhance Indian manufacturing. As a result, by not joining the RCEP, India shut themselves out of a trading bloc, which could have served as a huge export market for India to realise the potential of its manufacturing sector.

Finally, India has been given the time to rethink their decision, because for the RCEP, regional integration would be incomplete if India remains outside of it. Since India is the only South Asian country that is part of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) and has an FTA with ASEAN, India would have been the gateway for other RCEP member countries in the South Asia region through multilateral trading agreements. For now, India may have missed the chance to access a huge part of the North and Southeast Asian markets and vice versa. But the success of not signing the RCEP should be measured by the extent to which India is able to align the goals of foreign trade policy (2021-2025) with ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat,’ capitalise on the Make in India initiative and progressively cut down the trade deficit with the RCEP member countries in the coming years.

The author is Research Intern at ORF.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV