-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

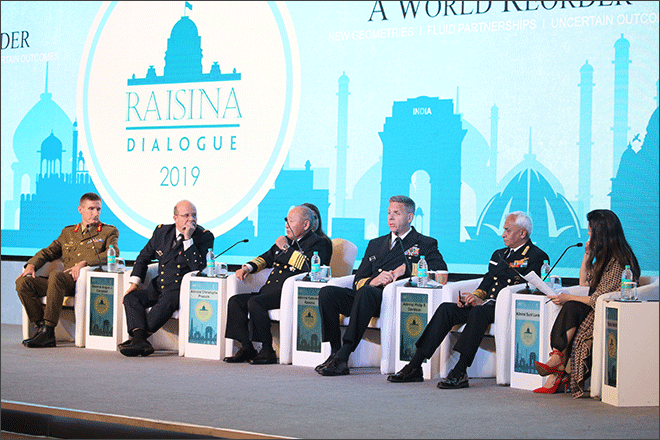

This year's Raisina Dialogue looked ahead of the disruptions that have agitated global politics for the past few years and interrogated what they mean for an emerging world order. As the international system rapidly drifts away from the moorings of its Atlantic origin, its future will be decided by the complex interactions among new actors, voices and demands. After a period of relative unipolarity at the turn of the century, we are entering a world that is not only multipolar but also ‘multiconceptual’.

Why multiconceptual? For one thing, the concentration of economic wealth is “relentlessly shifting eastwards,” as noted by Mark Sedwill, the UK’s National Security Adviser. This transformation will certainly create new 'poles' of power—India and China chief among them. It will simultaneously diminish the influence of extant powers. Spain's Minister for Foreign Affairs Joseph Borell alluded to this reality when he called on Europe to “influence or be influenced”.

Beyond the diffusion of economic power, the world is also grappling with an explosion of new actors, values and interests—from powerhouse cities to powerful multinationals and networked civil society groups.

Source: PhotoLabs@ORF

This global complexity is straining the ability of the international community to adapt and respond to the momentous social and economic transformations that are currently underway. Every year, dire warnings about the impact of climate change pass by unheeded. The global economy is being increasingly driven by digitisation and associated technologies, with returns accruing mainly to owners of capital. Economic opportunities and jobs for millions, on the other hand, are being lost to automation. Meanwhile, our institutions of governance are struggling to address tensions of inequality and identity.

Around the world societies are responding by taking solace in national solutions and populist prescriptions that promise to put local concerns ahead of global ones. Perhaps it is only natural that a period of geopolitical flux should coincide with a renewed emphasis on the power and authority of the state. The consequences of this trend for international norms and institutions, however, are dire. “The insecurity felt by millions will weaken respect for international law and institutions, human rights and the principles of collective security,” warned Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg as she inaugurated the 2019 Raisina Dialogue.

The insecurity felt by millions will weaken respect for international law and institutions, human rights and the principles of collective security

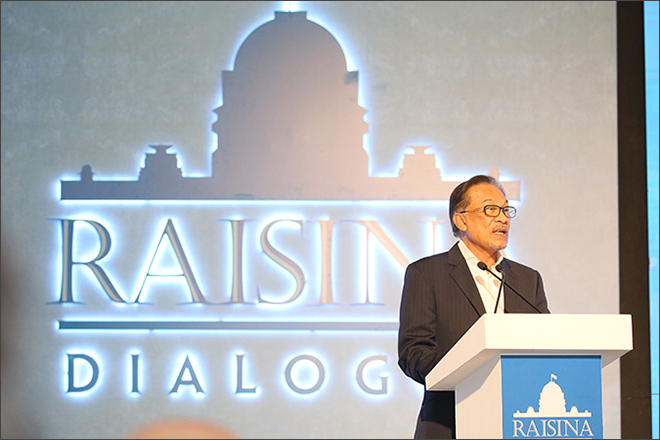

Source: PhotoLabs@ORF

More worryingly, the perception of exclusion reduces our collective capacity to arrive at a consensus. And in a world that is more interdependent—and more fragile—than ever before, finding solutions requires more, not less, international cooperation. How can multilateralism, then, be made relevant in a multiconceptual world?

To start with, we certainly require a new international framework to capture the diversity of reality, views and voices that exist today. Minister for External Affairs Sushma Swaraj said as much when she suggested that key public policy questions be asked in “villages and small towns, to school classrooms, and to vernacular media outlets.” She was alluding to the fact that the international system requires a new consensus which is more inclusive and diverse. It also requires a new ethos defined by the common interests and urges of the many, rather than the shared objectives and strategies of a few.

Second, the international community requires a new 'new deal'. This is true both domestically and for global governance. The Washington Consensus is no longer relevant in the fourth industrial revolution. The twin forces of globalisation and technological change will create new winners even as they leave many behind. Designing inclusive economic models will require new policies capable of balancing sovereign compulsions and global interdependence. They will also require unlikely partnerships at the global level. There is no reason, for example, that the NATO and the SCO cannot have influential conversations on the Indo-Pacific or Afghanistan or, for that matter, the BRICS and the G7 cannot harmonise their diverse economic models and expectations from a global trading regime.

Source: PhotoLabs@ORF

Third, new coalitions and partnerships must emerge. French Secretary-General for European and Foreign Affairs Maurice Gourdault-Montagne said “issues based alliances will proliferate if the international order continues to fragment.” However, such coalitions, especially between those with shared values and interests, have a role to play in supporting the international order in its period of transition. Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Marise Payne saw such potential in India, a country with which Australia could support a “rules-based order”. Such coalitions must be able to cut across geographies, issues and interests.

Fourth, global governance must account for new actors. Over 60 per cent of the world’s GDP is now generated in cities. The market capitalisation of the largest technology companies far exceeds the GDP of even significant countries. By this reckoning, Apple is bigger than Saudi Arabia. Solutions to big-ticket challenges like climate change and the future of work may well emerge from these networks of power and other key voices like think tanks and civil society organisations. Instituting new mechanisms for dialogue between such actors can create more effective global feedback loops.

Fifth, international institutions must reclaim some legitimacy. In the middle of the 20th century, the organising principle of 'one country-one vote' in international affairs resonated with many post-colonial societies. While global institutions have rarely proved truly democratic, it is evident that the key to legitimacy is a real distribution of decision making authority amongst stakeholders. India’s Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale warned that the “tussle between unilateralism and multilateralism” would continue unless international steering mechanisms are able to better capture today’s global realities.

Sixth, the international community must embrace informality. Formal global institutions can often be ineffective in responding to challenges that are sudden and complex. Informal coalitions and governance models, on the other hand, can summon the human and technological capital that is required to collaborate at scale. The global climate change agenda, for instance, is being quietly led by coalitions of cities from the global north and the global south. They are rapidly scaling and transferring innovation, ideas, resources and capital.

Seventh, the innocent appreciation of technology being benevolent and beneficial has changed the world over. Technology is now both a tool and an actor that can dramatically enhance quality of life and radically destabilise societies and nations. Foreign Secretary Gokhale captured the essence of this juxtaposition by suggesting that the rapid development of social sciences alongside science and technology is a prerequisite for ensuring that innovation benefits humankind. A new ethic of human engagement awaits discovery.

Technology is now both a tool and an actor that can dramatically enhance quality of life and radically destabilise societies and nations.

Last, though not the least, it is worth noting that securing geopolitical stability and protecting multilateralism will certainly require new stewardship. It is increasingly likely that in the coming years India will be a prime candidate for this role, even if only because India is a microcosm of the world at large. Rapid technological advances, a booming labour force and the imperative to develop in a resource-constrained world will define the 'India story' and, in turn, impact the future of billions in the developing world. Thus India presents a unique opportunity as an arena to resolve many of the world’s contradictions.

Source: PhotoLabs@ORF

India is a post-colonial state that has emerged as a vocal proponent of a liberal, rules-based international order. It is located at the intersection of Eurasia and the Indo-Pacific, two regions that will define the 21st century. And it has always been willing to navigate complexity by seeking shared objectives. Very few countries, for example, can claim to engage with powers like Russia and China while embracing a strategic partnership with the US. As Minister Swaraj noted in her address, “India’s engagement with the world is rooted in its civilisational ethos: co-existence, pluralism, openness, dialogue and democratic values.”

It is for this very reason that Dato Seri Anwar Ibrahim described India as “an enigma.” In many ways, the annual Raisina Dialogue is an attempt to deconstruct what makes it so and why this is relevant to the world. The feedback we have received from world leaders in the fields of politics, industry, media and civil society makes it clear that India’s choices matter more than ever before. Increasingly, the conversations that take place at the Raisina Dialogue are not only teasing out an Indian consensus on world affairs but a larger consensus capable of shaping a less unstable, more predictable world reorder.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Samir Saran is the President of the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), India’s premier think tank, headquartered in New Delhi with affiliates in North America and ...

Read More +