This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the resource incapacities of governments, supply chain risks of businesses, and the inherent social and economic inequalities in civil societies, resulting in isolated countries, fragile economies and an inward-looking world.

The gains of globalisation — which ensured the free movement of people, goods, services and capital, and brought the world closer — stands threatened and uprooted. Tough questions are being asked by affected countries across the world, amidst debates on decoupling, economic sovereignty and self-reliance, and a simultaneous rise of economic nationalism with accelerated digital integration. The message is clear — the ‘new normal’ has new aspirations, new players and revised allegiances, brought together by the consequences of the pandemic.

The impact of the pandemic on regular life has also been a catalyst for greater connectivity, cooperation and coexistence, effectively forcing a reimagination and discovery of new ways to grow and engage with the changing global reality

<1>. COVID-19 has indeed brought the future forward.

The message is clear — the ‘new normal’ has new aspirations, new players and revised allegiances, brought together by the consequences of the pandemic.

The Indo-Pacific is emerging as a new area of importance, driven by the common interests and convergences of several strategic powers, each with their own set of influences and ambitions

<2>, reflective of three emerging geostrategic and geoeconomics shifts. First, strategic competition over the next several decades will be dominated by maritime and blue economy. Second, the Indo-Pacific covers a diverse and big region that envelopes Southeast Asia, South Asia and the littoral nations of the Indian Ocean. Third, the rise of China, its outward expansion and the heightening of the US-China rivalry. The rivalry peaked during the pandemic, with countries jostling to identify partners for long-term strategic and economic cooperation, to go beyond unipolar or bipolar dynamics (US and China) of uncertainty, instability and supply chain risks. China’s unrelenting pressure on countries, its role in the pandemic crisis, its attempt to hijack global institutions like the World Health Organisation (WHO), its territorial aggression on India and using coercive trade practices to target Australia, has forced other countries to unite to address the situation they find themselves in. What is clear is that these countries have charted their own paths to self-realisation after experiencing some hard truths with China

<3>. The consolidation of the Indo-Pacific region could also offer alternatives to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, assert the need for a connected multipolar region of numerous middle powers, and their strategic and economic aspirations

<4>.

The concept of the Indo-Pacific is internalised in diverse ways by its proponents. Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe committed his country to a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) strategy in 2016 and ex-US President Donald Trump asserted the FOIP strategy in 2017, both with the aim of ensuring rule of law and freedom for shared prosperity. In India and Australia, the Indo-Pacific is primarily treated as a normative framing. And in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), it is as an “outlook” with a strong departure from the China containment logic and is based on inclusivity and equidistance from the US and China. Similarly, France and Germany have outlined Indo-Pacific strategies that stress middle-power co-operation on issues such as climate change and regional governance. Pacific Island states have been most hesitant with the FOIP concept, which implies making a strategic choice between China and others

<5>.

The concept of the Indo-Pacific is internalised in diverse ways by its proponents.

In the

Contest for the Indo-Pacific: Why China Won’t Map the Future, Rory Medcalf writes that “The Indo-Pacific, is unified by the quest to balance, dilute and absorb Chinese power, it is both a region and an idea — a metaphor for collective action, self-help combined with mutual help, it is a mental map which speaks of power, strategic imagination, and a world view. It is inherently a multipolar region because it is too large for hegemony. This calls for partnerships among nations in order to preserve order

<6>.”

India in the Indo-Pacific

India’s definition of the Indo-Pacific region stretches from the western coast of North America to the eastern shores of Africa.

The vast Indo-Pacific region comprises at least 38 countries, shares 44 percent of the world surface area, is home to more than 64 percent of the world’s population, and accounts for 62 percent of the global GDP with more than 50 percent of global trade traversing through its waters

<7>. The region is highly heterogeneous with countries at different levels of development connected by a common thread of 'the ocean

<8>.’

Prime Minister Narendra Modi articulated India’s Indo-Pacific concept as the SAGAR doctrine — ‘Security and Growth for All in the Region’, an aspiration that depends on ensuring prosperity for all stakeholder nations, guided by norms and governed by rules, with freedom of navigation

<9>. In 2019, at the East Asia Summit in Bangkok, India announced the Indo-Pacific Oceans’ Initiative (IPOI) to support the building of a rules-based regional architecture centred on seven pillars — maritime security; maritime ecology; maritime resources; capacity building and resource sharing; disaster risk reduction and management; science, technology and academic cooperation; trade, connectivity and maritime transport

<10>.

Indo-Pacific Oceans’ Initiative is anchored on India’s ‘Act East’ (focusing on the Eastern Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific) and ‘Act West’ (focusing on the Western Indian Ocean) policies.

IPOI is anchored on India’s ‘Act East’ (focusing on the Eastern Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific) and ‘Act West’ (focusing on the Western Indian Ocean) policies

<11>. It seeks to widen the scope of the Indo-Pacific narrative by including a diverse set of challenges and opportunities that go beyond traditional security threats and geostrategic concerns. It also includes economic, environmental and technology related challenges in the maritime domain. The architecture is inclusive, cooperative and open, where any two or more nations can collaborate in a particular sector. For instance, India and Australia are collaborating in maritime security and safety, and protecting the Indo-Pacific marine environment

<12>.

India’s Indo-Pacific priorities incorporate its closest neighbours (all South Asian countries), followed by its outer neighbourhood (Gulf states in the west and Southeast Asian and ASEAN countries in the east). India has also built partnerships and collaborated with likeminded countries in the region that have shared values and common goals — from the Pacific Islands to the archipelagos of the western Indian Ocean and off the eastern coast of Africa; to networks such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) with the US, Japan and Australia, the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) with Japan and Australia as participants, and the India-Japan-US, India-France-Australia and the India-Indonesia-Australia trilateral arrangements. These are all strong instances of cooperation, which will be nurtured and solidified in the post-pandemic world with new coalitions and effective operational outcomes

<13>.

India’s Indo-Pacific priorities incorporate its closest neighbours (all South Asian countries), followed by its outer neighbourhood (Gulf states in the west and Southeast Asian and ASEAN countries in the east).

According to Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar, the “Indo-Pacific construct signifies the confluence of the Indian and Pacific oceans that can no longer be handled as distinct spheres. It is a reiteration that the world cannot be frozen for the benefit of a few, the security, stability, peace, and prosperity of this vast region is vital for the world. The Indo-Pacific concept is not tomorrow’s forecast but yesterday's reality. It captures a mix of India’s broadening horizons, widening interests, and globalised activities. The Indo-Pacific is central to India’s exports and imports

<14>.”

In April 2019, India established a new division for the Indo-Pacific in its Ministry of External Affairs to address the region’s growing salience in global discourse. The division converges the Indian Ocean Rim Association, the ASEAN region and the QUAD under one umbrella.

India’s Indo-Pacific expanse largely covers:

• Matters of Indo-Pacific includes the QUAD, along with trilateral groupings India–Japan–US, India–Australia–Indonesia, India–Australia–Japan (SCRI), India–France–Australia

• India–ASEAN relations includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam

• East Asia Summit includes the ten ASEAN countries along with Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea, Russia and the United States

• Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), India’s Indo-Pacific policy is rooted in the Indian Ocean and includes Australia, Bangladesh, the Comoros, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Madagascar, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritius, Mozambique, Oman, Seychelles, Singapore, Somalia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen. IORA has ten dialogue partners — China, Egypt, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Turkey, the Republic of Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States

• Asia–Europe Meeting (ASEM), includes 21 Asian countries and the ASEAN Secretariat along with the European Union and its 27 member states, plus Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom

• Mekong–Ganga Cooperation (MGC) includes India and five ASEAN countries, namely, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam

• Ayeyawady–Chao Phraya–Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) includes Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam — India was included as a development partner in 2019

• Oceania includes Australia, New Zealand and Pacific Island countries

• Eastern Africa includes Somalia, Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, South Africa, Mauritius, Seychelles, Madagascar and Comoros

• Gulf Arab States includes, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates

• North America includes United States and Canada, including the regions of Central America and the Caribbean islands

|

Although India has focused on building strong strategic and security partnerships in the Indo-Pacific, discussions on the economic potential of the region remain less developed. However, India’s strategic priority for ensuring peace, stability, security and prosperity in the region (articulated through IPOI) is integrated with its goals of building a thriving ‘blue economy’, vital to the nation’s economic growth and post-COVID-19 economic recovery.

Indian Ocean Region: Pivot for India’s economic ties with Indo-Pacific

The heart of India’s economic ties in the Indo-Pacific is rooted in the Indian Ocean (see Figure 1). The Indian Ocean is almost 20 percent of the world’s ocean area, touching the shores of 36 countries and connecting three continents (Africa, Asia and Australia), with a total coastline area of 66,526 km, or 40 percent of the global coastline. The Indian Ocean is home to major sea-lanes and choke points that are crucial to global trade, connecting major centres of the international economy in the North Atlantic and Asia-Pacific — 90,000 commercial shipping vessels form the backbone of international goods trade; and about 40 percent of the world’s oil supply travels through strategic choke points into and out of the Indian Ocean, which is also a valuable source of mineral and fishing resources. Currently, within the Indian Ocean region, East Asia and the Pacific outperforms South Asia, West Asia and Africa on all aspects of economic dynamism of the Indian Ocean, leaving countries to identify and address the gaps that exist

<15>.

Figure 1: India’s Growth Pivot to the Indian Ocean

Source: Author’s own

Source: Author’s own

India’s economic future in the Indo-Pacific region will largely be defined by its capacity to build on its blue economy potential (ranging across several sectors), regional economic integration (trade agreements to address trade barriers) and connectivity infrastructure to promote intra-inter regional trade (ports and logistics) in the Indian Ocean.

India’s blue economy potential: Sectors and activities

The blue economy has a 4.1-percent share in India’s GDP, with immense potential for growth (see Table 1)

<17>. Modi has stressed the importance of the ocean economy by likening it to the blue

chakra (wheel) in India’s national flag

<18>.

Table 1: Resources from an Ocean Economy

| Sector |

Activity |

| Fishing |

Capture fishery (addressing the problems of overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, fishing in high and open seas), aquaculture, seafood processing, to emphasise the optimum use of fisheries |

| Marine biotechnology |

Pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, nutritional supplements, molecular probes, enzymes, fine chemicals and agrichemicals, seaweed harvesting, seaweed products, marine-derived bio-products |

| Minerals |

Oil and gas, deep-sea mining (exploration of rare earth metals, hydrocarbons) led by rising demand and use of these critical minerals in advanced applications |

| Marine renewable energy |

Offshore wind energy production, wave energy production, tidal energy production |

| Marine manufacturing |

Boat manufacturing, sail making, net manufacturing, boat and ship repair, marine instrumentation, aquaculture technology, water construction, marine industrial engineering |

| Shipping, port and maritime logistics |

Ship building and repairing, ship owners and operators, shipping agents and brokers, ship management, liner and port agents, port companies, ship suppliers, container shipping services, stevedores, roll-on roll-off operators, custom clearance, freight forwarders, safety and training. India’s Sagarmala project and its draft Maritime Vision 2030 document aims to boost development through promotion of ports and shipping. The port-led development plan is based on four pillars of port modernisation, connectivity, port-led industrialisation and coastal community development. |

| Marine tourism and leisure |

Water sports, coastal natural reserves |

| Marine construction |

Marine construction and engineering |

| Marine commerce |

Marine financial services, marine legal services, marine insurance, ship finance & related services, charterers, media and publishing |

| Marine information and communication technology (ICT) |

Marine engineering consultancy, meteorological consultancy, environmental consultancy, hydro-survey consultancy, project management consultancy, ICT solutions, geo-informatics services, yacht design, submarine telecom |

| Education and research |

Education and training, research and development |

Source: Blue Economy Report 2015, RIS <19>

Regional economic integration and connectivity infrastructure

The Indian Ocean economy is expected to account for over 20 percent of global GDP by 2025

<20>. India’s share in the growing Indian Ocean economy will be dictated by its improved port quality and logistics, lowered barriers to trade and investment, strengthened regional economic governance, and ability to balance geopolitical tensions. India’s current statistics on economic integration and infrastructure highlight the substantial room for improvement (see Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Table 2: Status of India’s Economic Integration and Infrastructure

|

Benchmark component

0-100 (best) |

Overall score |

Overall rank |

Rank compared across nations |

|

Quality of port infrastructure (2019)

Liner shipping connectivity

Efficiency of seaport services |

59.9

59.1 |

25

49 |

Across 141 economies |

|

Trading across borders (2020)

Time to export, border compliance |

82.5 |

68 |

Across 190 economies |

|

Trade openness (2019)

Prevalence of non-tariff barriers

Trade tariffs percent

Complexity of tariffs

Border clearance efficiency |

57.6

3.8

65

49.1 |

66

134

87

41 |

Across 141 economies |

|

Global Innovation Index – India

(2020) |

|

48 |

Across 131 economies |

|

Logistics Performance Index, LPI (2018)

Overall (1=low to 5=high)

Customs

Infrastructure

International shipments

Logistics competence

Tracking and tracing

Timeliness |

Overall LPI Score: 3.18

2.96

2.91

3.21

3.13

3.32

3.50 |

44 |

Across 160 economies |

Source: Author’s own, from various sources (20)

Table 3: India’s Non-Tariff Measures

|

| Sanitary and phytosanitary |

247 |

| Technical barriers to trade |

193 |

| Anti-dumping |

313 |

| Countervailing |

20 |

| Safeguards |

4 |

| Quantitative restrictions |

59 |

| Tariff-rate quotas |

3 |

Source: WTO, December 2020 <21>

Table 4: India’s Free Trade Agreement Status, 2020

|

Under negotiation

Framework Agreement signed – 1

Negotiations launched – 16 |

Signed but not yet in effect |

Signed and in effect |

Total |

| 17 |

0 |

13 |

30 |

Source: ADB, Dec 2020 <22>

Advancing India’s interest in the Indo-Pacific

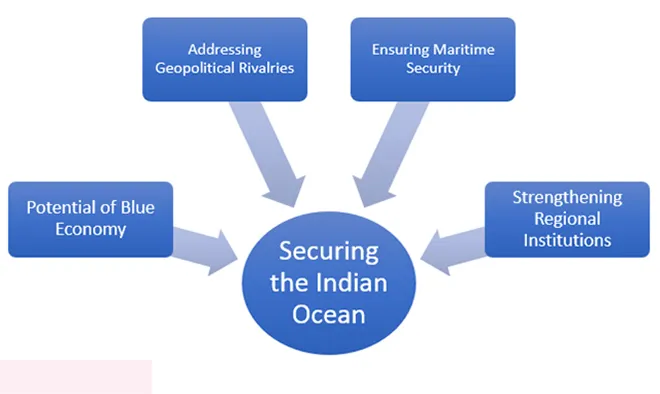

At the core of the Indo-Pacific region is a collection of sub-regions of diverse countries, each with different strengths, capabilities and capacities. The countries within these sub-regions are creatively and strategically building the Indo-Pacific narrative. Going forward, India needs a crafted and coherent Indo-Pacific strategy to navigate the competitive, complex and contested region. This is critical to maximise its economic opportunity and maintain its maritime security.

India can experiment with the ways of alignment (bilaterals, minilaterals and multilaterals with countries in the region)

<23>, and address existing drivers, barriers and inhibitions within countries or sub-regions in a more focused manner. This will include securing the Indian Ocean, deeper integration with Southeast Asia, strong partnerships with other strategic powers (such as the US, Japan, Australia, France and the UK), managing China, investing in maritime logistics and infrastructure, reducing barriers to trade and investment, and strengthening regional economic governance via regional and bilateral trade agreements.

At the core of the Indo-Pacific region is a collection of sub-regions of diverse countries, each with different strengths, capabilities and capacities.

There is considerable work to be done and much to build on. India can consider the following recommendations:

• ASEAN is at the centre of India’s Indo-Pacific vision. India can consolidate deeper ties with the East Asian economies at a bilateral level and minilateral level, irrespective of its non-engagement on multilateral platforms like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) or Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. The ASEAN region and India make up one-fourth of the global population and their combined GDP has been estimated at over US$ 3.8 trillion<24>.India should also consider playing a proactive leadership role in minilateral organisations such as the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation and the Mekong–Ganga Cooperation, both of which include ASEAN member countries<25>. India must bolster its economic cooperation with ASEAN further, in sectors like infrastructure, fintech, information technology/information technology enabled services, e-commerce, education and skill development, healthcare and pharmaceuticals, and agriculture and food processing<26>. Continuing Indo-Pacific economic integration also asks for establishing greater physical infrastructure and connectivity between South and Southeast Asia, supported by stronger private sector participation, which requires substantial funds (US$ 8 billion currently, against the overall need for US$ 73 billion)<27>. This could also provide the right impetus to complete the pending India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway and the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport.India’s state governments must also proactively align with the central government’s Act East policy. ASEAN and India can also consider upgrading the ASEAN-India free trade agreement to promote sustainable, inclusive and resilient growth<28>. This has to be supplemented with stronger ease of doing business reforms at home and state governments honouring business agreements.

• India’s evolving ties with Australia, with the elevation of the relationship to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership and the release of India’s economic strategy for Australia and vice versa, offers opportunities to create a dependable partnership in the Indo-Pacific<29>. In September 2020, India created a new vertical in its foreign ministry, with the Oceania territorial division and Australia at its centre and including ASEAN and the Indo-Pacific divisions<30>. India and Australia strategically anchor the Indo-Pacific in the northwest and southeast. India surrounds the Indian Ocean and Australia lies between the Indian and the South Pacific Ocean<31>. The Australia and India free trade deal (Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement) has been in works since 2011, with over nine rounds of negotiations, but the two countries have yet to reach a settlement. Gains from the pact are estimated to be in the range of 0.15 percent and 1.17 percent of GDP for both countries, and will likely boost confidence in the business environment; bolster export in sectors like agriculture, food processing, mining and resources; and facilitate investment flows. Robust ties between the two countries will pave the way for a stronger Indo-Pacific economic architecture<32>.

• The revival of the QUAD and SCRI grouping were motivated by shifts in the regional order in the Indo-Pacific<33>. However, the degree of shared ambition among the countries in these groups vary, driven by their outlooks, interests and approaches, specifically on trade liberalisation and membership of multilateral organisations — for instance, Australia and Japan are members of Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, APEC, RCEP and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.India must find common points of interest and collaboration with each country and address the economic dependencies on China independently (India’s trade exposure to China is at 11 percent of two-way trade, Japan’s is twice as high and Australia’s a massive 30 percent). All partner countries have shared interests and outlook in sectors like critical minerals and infrastructure<34>. India will also need to reflect on SCRI’s goal in the region — supply chain reconfiguration or ensuring supply chain efficiency by addressing the stretched balance sheets of companies across sectors and the inhibition to move and relocate<35>. These factors will determine the emergence of the Indo-Pacific region as a hub of global value chains-oriented trade and investment.

• Economic growth in Indo-Pacific countries can only be revived by sound economic (power, water and transport) and social infrastructure (education and health). Connectivity and inclusivity in the region must be based on comprehensive policies (robust legal and regulatory framework, interagency coordination) that can attract investment in infrastructure, build financial systems and shape digital economies — a necessary step to realise the Indo-Pacific trade potential<36>. Private investment in infrastructure must be mobilised. Out of the US$ 50 trillion global stock of capital managed by pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurance companies and other institutional investors, only 0.8 percent is allocated to infrastructure<37>.

• The pandemic has reversed decades of progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, with collateral damage to education, health and nutrition<38>. It has exacerbated social and economic inequalities and has exposed global disparities. Countries in the Indo-Pacific must work together to create a resilient development paradigm to address this severe humanitarian crisis. The ultimate test of India’s diplomacy in the Indo-Pacific should not be limited to exports, investment and its strategic clout, but also importantly how it has improved the standards of living.

• India should prioritise creating a full-fledged Ministry of Blue Economy, with an effective institutional mechanism for coordination and leadership<39>. This will put all components of a blue economy, including security, maritime budgetary allocation, naval acquisitions, maritime trade, energy needs, transportation, connectivity, fisheries and marine exploration, under a single ambit.

• Sectors like automobiles, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, advance manufacturing, critical minerals, healthcare, education, infrastructure, science and innovation, and technology transfer could offer opportunities for regional recovery and also build substantial intellectual capital to address shared challenges<40>. India could provide inclusive and creative leadership driven by reciprocity in the region, provided it focuses on capacity building across government institutions and business organisations, market integration and regional links with established norms for stronger economic cooperation. There must be greater convergence of goals, supported by coordinated actions.

• India will need to develop a multi-layered approach towards cooperation in the region, matching its strengths and priorities with other countries, building inter-trade facilitation centres, with a focus on niche goods and services, and using technology to build responsive processes<41>. India’s institutional competence is central to achieving these economic goals in the region, which should include specialised departments of competitiveness and industrial development, trade policy and negotiation.

• Economic diplomacy and domestic reforms are intricately linked. How India chooses to engage with the world will primarily depend on its ability to build a new narrative around its strengths and offerings, its capacity to build new engines of growth and productivity (like its pharmaceuticals, automotive and telecom sectors), its drive to prosper and grow and look out for the world, and its commitment and ability to engage at granular and macro levels<42>. India should also focus on developing a sophisticated knowledge base on countries in the region.

Social and economic inequality in the Indo-Pacific region will challenge its full economic integration. Hence, post-COVID-19 economic diplomacy must create long-term solutions that ensure the ‘new normal’ is more equitable than the previous one. The metrics of engagement must be defined differently, not just based on flows of physical goods, money and people, but on the basis of building capacity-led connections, complementarities, sustainable commitments and mutual dependence across countries and sub-regions.

The ‘new normal’ economic diplomacy should seek for balance between competition and cooperation, aspirations and the achievable, and regional and global. It should be navigated on the strong foundation of rules-based collaboration. India’s concerted actions in the Indo-Pacific region will determine its evolution as a key player. This requires a reimagination, reform, resolve and resilience based on trust and transparency. It is no longer about rising India, but how India could lead.

Endnotes

<1> Navdeep Suri, Biren Nanda and Anil Wadhwa, “

A New Global Reality with The Ambassadors,” (webinar, Australia–India Webinar Series, Newland Global Group, Sydney, 24 April 2020), YouTube.

<2> Rory Medcalf and C Raja Mohan, “

Responding to Indo–Pacific Rivalry: Australia, India, and Middle Power Coalitions,”

Lowy Institute Analysis, August 2014.

<3> Natasha Jha Bhaskar, “

India-Australia are the architects of a new World Order,”

India Global Business, India Inc., 23 September 2020.

<4> Roland Rajah, “

Mobilizing the Indo-Pacific infrastructure response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia,”

The Brookings Institution, April 2020.

<5> Joanne Wallis, Sujan R. Chinoy, Natalie Sambhi and Jeffrey Reeves, “

A Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Opportunities for Engagement,”

Asia Policy, Volume 15, Number 4: 1-64 (October 2020).

<6> Rory Medcalf,

Contest for the Indo-Pacific: Why China Won’t Map the Future (Victoria: LaTrobe University Press, 2020).

<7> Prabir De, “

Navigating the Indo-Pacific Cooperation,”

Economic Times, 11 March 2019.

<8> Tridivesh Singh Maini, “

Indo-Pacific Economic Corridor: Opportunities and Challenges,” (speech, ICRIER Young Scholars’ Forum, Japan Foundation, 24 June 2016), East Asia Research Programme.

<9> Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2018.

<10> Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 2019.

<11> Premesha Saha and Abhishek Mishra, “

The Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative: Towards a Coherent Indo-Pacific Policy for India,”

Observer Research Foundation, December 2020.

<12> Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Government of Australia.

<13> Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

<14> S. Jaishankar (speech, CII Partnership Summit, 17 December 2020),

YouTube.

<15> Ganeshan Wignaraja, Adam Collins and Pabasara Kannangara, “

Is the Indian Ocean Economy a New Global Growth Pole?”

The Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies, October 2018.

<16> Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister,

Report of Blue Economy Working Group on National Accounting Framework and Ocean Governance, EACPM, September 2020.

<17> Narendra Modi, “

Text of the PM's Remarks on the Commissioning of Coast Ship Barracuda” (speech, 12 March 2015), Narendra Modi.

<18> S.K. Mohanty, Priyadarshi Dash, Aastha Gupta and Pankhuri Gaur, “

Prospects of Blue Economy in the Indian Ocean,”

Research and Information System for Developing Countries, 2015.

<19> Ganeshan Wignaraja, Adam Collins and Pabasara Kannangara, “

Is the Indian Ocean Economy a New Global Growth Pole?”

The Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies, October 2018.

<20> World Economic Forum,

The Global Competitiveness Report 2020, World Economic Forum, 2020; Doing Business, “

Trading across Borders,” World Bank; WTO, “

Trade and Tariff Database,” WTO; World Integrated Trade Solution, World Bank; Development Economics Research Group, “

Services Trade Restrictions Database,” World Bank; World Bank, “

Aggregated LPI,” World Bank; World Intellectual Property Organization, “

Global Innovation Index 2020,” WIPO.

<21> World Trade Organisation, “

Trade and Tariff Database,” WTO.

<22> Asia Regional Integration Center, “

Free Trade Agreements,” ADB.

<23> John West, “

The Indo-Pacific Contest,” review of

Contest for the Indo-Pacific: Why China Won’t Map the Future, by Rory Medcalf,

The Interpreter, 13 June 2020.

<24> Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

<25> Mustafa Izzuddin, “

India has left RCEP behind, but not its ambition in Southeast Asia”,

The Interpreter,

Lowy Institute, 13 January 2020.

<26> PHD Research Bureau,

India’s Trade and Investment Opportunities with ASEAN Economies, PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry, November 2019.

<27> Shankari Sundararaman, “

Indo-Pacific economic corridor: A vision in progress,”

Observer Research Foundation, 25 January 2017.

<28> Prabir De, “

View: 17th ASEAN-India Summit, a turning point of ASEAN-India relations in post-COVID world,”

Economic Times, 11 November 2020.

<29> Department of Foreign Trade and Affairs, Australian Government;

Department of Foreign Trade and Affairs, Australian Government; Confederation of Indian Industry and KPMG, India,

Australia Economic Strategy, CII and KPMG, 2020.

<30> Natasha Jha Bhaskar, “

India's Australia Economic Strategy: A big push to bilateral trade,”

Business Today, 27 December 2020.

<31> Premesha Saha, Ben Bland and Evan A. Laksmana, “

Anchoring the Indo Pacific: The Case for Deeper Australia-India-Indonesia Trilateral Cooperation,”

Observer Research Foundation, January 2020.

<32> Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia Government and Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Department of Commerce, Government of India,

Australia – India Joint Free Trade Agreement (FTA): Feasibility Study, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2010.

<33> Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Department of Commerce, Government of India.

<34> Jeffrey Wilson, “

Investing in the economic architecture of the Indo-Pacific,”

Indo-Pacific Insight Series, Volume 8 (August 2017), Perth USAsia Centre.

<35> Ken Heydon, “

Domestic policies key to the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative,”

East Asia Forum, 21 September 2020.

<36> Mohammad Masudur Rahman, Chanwahn Kim and Prabir De, “

Indo-Pacific cooperation: What do trade simulations indicate?”

Journal of Economic Structures, Vol. 9, no. 45 (2020).

<37> PwC,

Developing Infrastructure in Asia Pacific: Outlook, Challenges and Solutions, PwC, Australia, May 2014.

<38> United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs,

The Sustainable Development Goals Report, 2020, New York, NY, UN2020, 2020.

<39> “

Blue Economy, Vision 2025 – Harnessing Business Potential for India Inc. and International Partners,”

FICCI Task Force, April 2017.

<40> Aakriti Bachhawat, Danielle Cave, Jocelinn Kang, Dr Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan and Trisha Ray, “

Critical technologies and the Indo-Pacific Policy, A new India–Australia partnership,”

Policy Brief Report No. 39/2020, Observer Research Foundation and Australian Strategic Policy Institute and International Cyber Policy Centre.

<41> Pritam Banerjee, “

A Commerce Ministry for the 21st century,”

The Hindu BusinessLine, 27 October 2020.

<42> Amitabh Kant, RS Sodhi, Manish Gupta and Dipen Rughani, “

Resetting Global Supply Chains – India’s Opportunity,” (webinar, Australia–India Webinar Series, Newland Global Group, Sydney, 10 June 2020), YouTube.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication —

This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication —  Source: Author’s own

Source: Author’s own PREV

PREV