The India-Japan partnership, described as one of the most rapidly advancing relationships in Asia, has emerged as a significant factor contributing to the stability and security of the Indo-Pacific region. Deviating from the traditional policy of focusing on economic engagements, the partnership has significantly diversified to include a wide range of interests—including regional cooperation, maritime security, global climate, and UN reforms. Both India and Japan also share several common ideals like democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, in addition to the complementarities that bind their economies.

An important aspect of the partnership is that it has always enjoyed bipartisan support in the domestic political spectrum. In 2000, then Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, with his Japanese counterpart, Yoshiro Mori launched the global partnership between the two countries. During the period 2004-14, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh laid the foundation for a stable partnership. Narendra Modi, PM Singh’s successor, went several steps further to make the bilateral relationship a strategic and global partnership for the peace and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific region.

When Modi took over as India’s prime minister in May 2014, he found his Japanese counterpart Shinzo Abe equally interested in promoting closer security and economic relations with India. Soon, both leaders developed a strong personal chemistry. From an Indian standpoint, Japan—a technological powerhouse with immense financial strength—could fulfil development needs in various spheres including infrastructure.

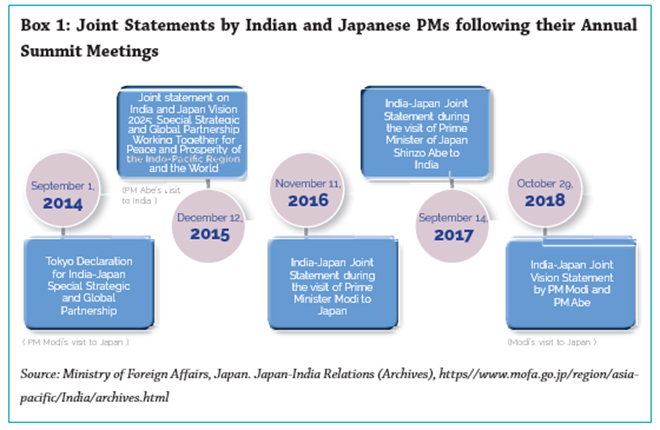

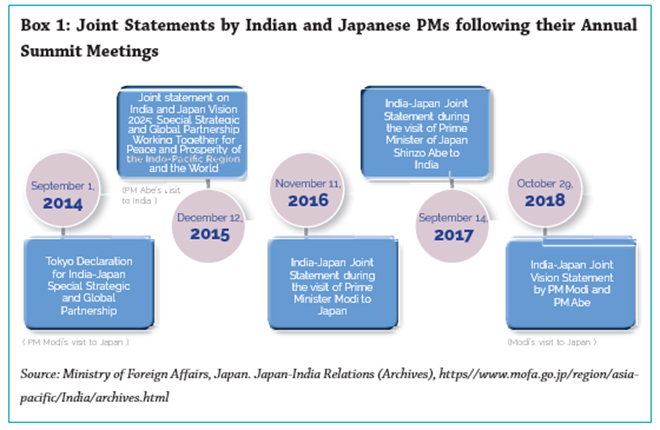

Modi attached great importance to the annual summit meetings with Japan during his first term, and between 2014 and 2018 there were five summit meetings held alternately between Tokyo and Delhi. Modi’s 2014 visit was followed by visits in 2016 and 2018. Similarly, Abe visited India in 2015 and 2017, and is due to visit later this year as well. The very first meeting held in Tokyo set the tone by issuing the Tokyo Declaration, which elevated bilateral ties to a special ‘Strategic and Global Partnership’ (See Box 1).

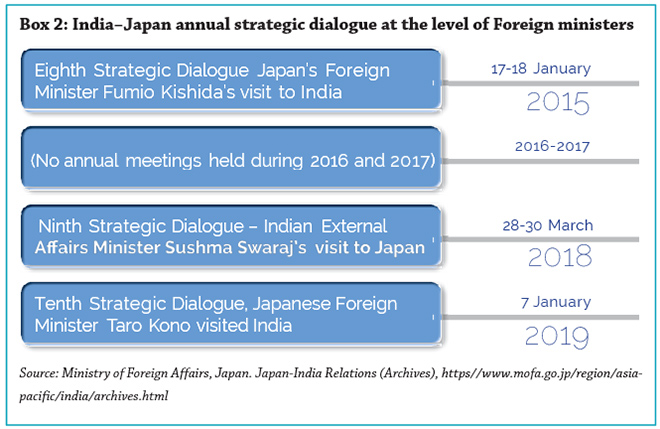

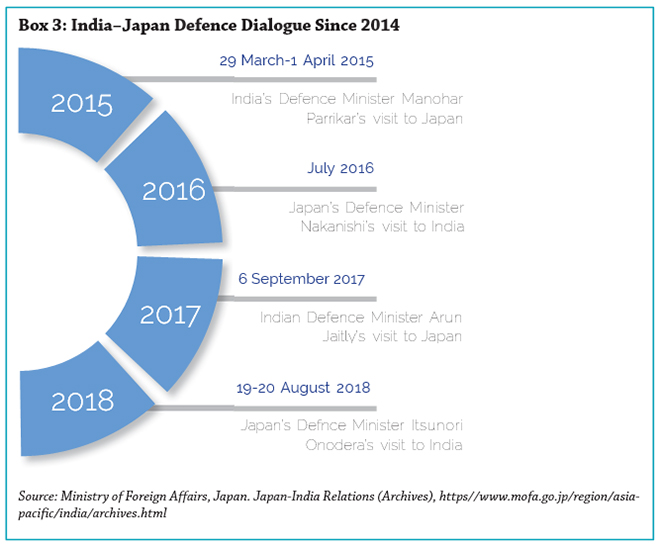

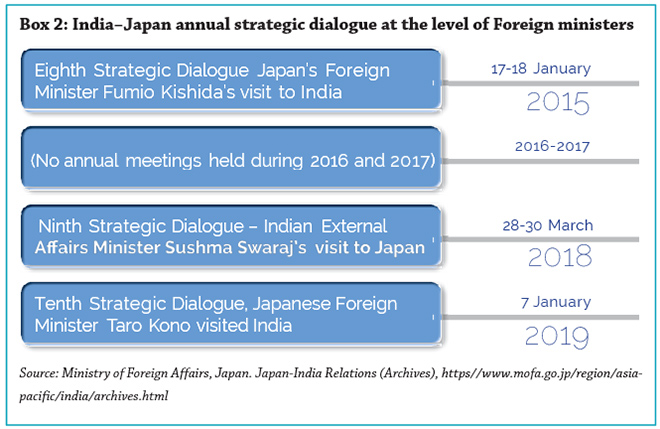

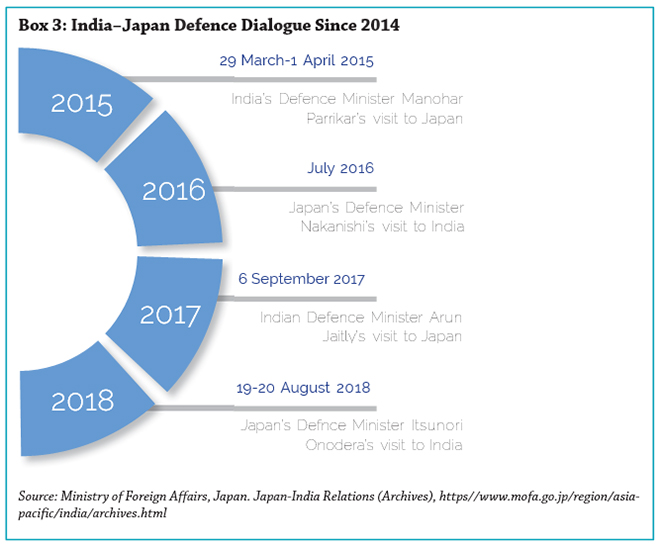

Emphasising the need for closer coordination between the two countries to address regional security challenges, Modi has supported robust defence cooperation with Japan. Such cooperation has been expanding in recent years and is buttressed by the regular Annual Strategic Dialogue between the two foreign ministers (See Box 2) and the Defence Dialogue between the two defence ministers (See Box 3). In addition, there have been regular exchange visits by the respective Service Chiefs as well as the two National Security

Advisers. Further, at the 2018 summit, Modi and Abe agreed to create a new Foreign and Defence Ministerial Dialogue to further strengthen defence cooperation.<1> In addition, Modi has elevated the US-India-Japan trilateral dialogue to the ministerial level. There is also greater coordination between India, Japan, the US, and Australia under the Quad format.

In 2014, the two countries signed the Memorandum of Cooperation and Exchanges in the Field of Defence. This was followed by two more framework agreements in 2015 on the transfer of defence equipment and technology, and security measures for the protection of classified military information. Both Modi and Abe have discussed the possibility of India acquiring Japanese technology in the production of submarines. They have also supported the “commencement of cooperative research in areas like Unmanned Ground Vehicles and Robotics.”<2>

Now that the Japanese government has relaxed the rules governing the export of Japanese defence technology, there is ample scope for enhancing mutual cooperation in defence. PM Modi has shown great interest in Japan playing a key role in India’s defence production, since the Indian government has also considerably relaxed rules to encourage the entry of foreign technologies in the defence field under the ‘Make in India’ scheme. In this context, it is important to note that both nations are keen to continue efforts to cooperate on the issue of purchasing Japan’s US-2 amphibian aircraft.<3> The deal, when signed, will be a landmark in Indo-Japanese defence cooperation.

After protracted negotiations, both countries also signed a milestone agreement on civil nuclear cooperation in 2016—this could open new opportunities for close bilateral interaction in the energy sector.

Maritime security is another important subject on which both India and Japan have convergent interests. Both countries depend critically on sea- borne trade for sustaining their economies. Both are strongly committed to respecting freedom of navigation and overflight, and unimpeded commerce in open seas. Regarding the disputes in the South China Sea, they have affirmed that all parties involved in the disputes should seek solutions through peaceful means without resorting to threats, use of force, or unilateral action.

As for their bilateral maritime cooperation, both navies are conducting annual exercises, with Japan participating in the annual India-US Malabar exercises on a regular basis. Now, the three countries conduct joint exercises in all the three wings of the defence forces.

With regard to China, both Modi and Abe share concerns on a range of issues including the future role of China in the Indo-Pacific region, Beijing’s assertive maritime postures in the Indian Ocean, and its Belt and Road Initiative. At a time when the Indo-Pacific region is faced with critical strategic challenges, both leaders have maintained a policy of engaging with Beijing. They are realistic enough to understand that in any future regional strategic scenario, because of its economic and military strength, China will figure quite prominently. It is therefore necessary to ensure that the rise of China takes place without disturbing the prevailing regional equilibrium. Interests of both India and Japan will be best served if the Indo-Pacific region remains multipolar with no single regional power assuming a preponderant position. Expanded economic engagement along with greater transparency in Chinese military strategies in the region could make Beijing a “responsible stakeholder.”

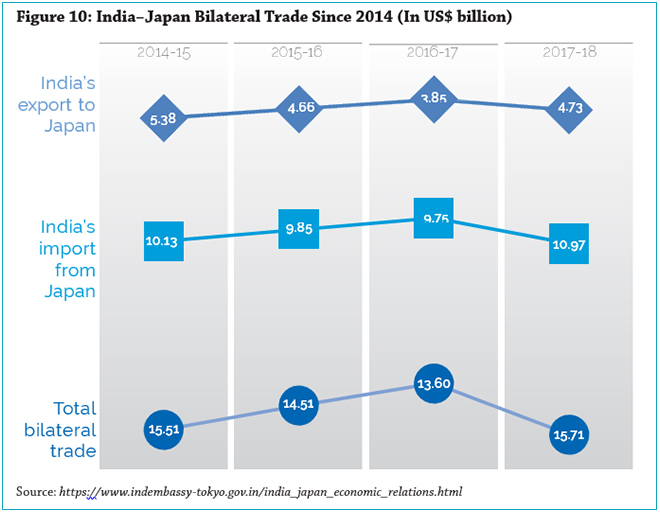

Despite the increasing importance of the strategic factor, economic cooperation continues to form the bedrock of the partnership and Modi has shown a great deal of interest in Japan getting deeply involved in several important Indian infrastructure projects. Praising Japan for having done more for India’s modernisation than any other country, Modi asserted that Japan’s technological and economic prowess could accelerate India’s development by transforming its infrastructure and manufacturing sectors.

In their first bilateral summit held in Tokyo, both Modi and Abe set the target of doubling Japan’s direct investment and the number of Japanese private companies in India. Japan agreed to extend US$33.5 billion public and private investment in India apart from funding from the Official Development Assistance (ODA) over five years. This amount would be used to support projects in several areas including infrastructure, connectivity, transport, smart cities, energy, and skill development. Modi decided to set up a number of industrial townships and electronic parks for developing technology, connecting people, and inspiring innovation. In turn, Abe affirmed that Japan would support India’s ‘Make-in India’, ‘Digital India’ and ‘Skill India’ programmes.

Between 2014 and 2018, the amount and quality of Japan’s ODA as well as Japanese private investment witnessed appreciable improvement. India remained on top of the list of ODA recipients and the economy gained numerous benefits from Japan’s ODA loans, which flowed into many critical sectors like power, transportation, communication, environment, water, public health, and agriculture.<4>

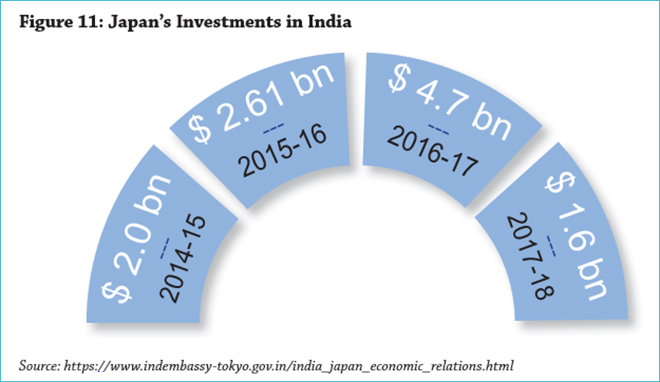

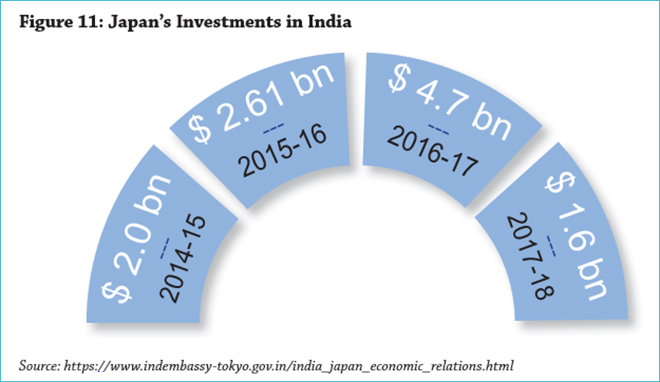

The quantum of Japanese private investment has increased since 2014, owing to Indian government efforts—like the creation of a special Japan- Plus desk at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry with a view to reduce

bureaucratic hurdles in clearing new investment projects. The quantity of Japanese investment increased from US$1.7 billion in 2014 to US$4.7 billion in 2016-17 (See Figure 11). With a cumulative Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) of US$25.2 billion from April 2000 to December 2016, Japan is the third largest investor in India—accounting for eight percent of India’s total FDI. Japanese investment has flowed into the automobile, telecommunication, chemical and pharmaceutical sectors.<5>

Modi has, from the beginning, emphasised the importance of India’s Northeast region (NER) in his “Act East Policy.” He has taken a special interest in Japan playing a key role in the development of the NER. Modi and Abe established the India-Japan Act East Forum, which will provide a platform for bilateral collaboration and identify projects for economic and social development of the region.<6> Both leaders consider the NER as a critical region, where India’s Act East Policy and Japan’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy” converge,<7> and both countries are keen to extend their cooperation to the larger Indo-Pacific region—including the African continent.

In May 2016, Modi announced a proposal to develop an Asia-Africa Growth Corridor with the support of Japan.<8> This proposal is aimed at creating a “free and open Indo-Pacific region” by building a series of sea corridors that would connect the African continent with India and other countries of South and Southeast Asia. One important objective is to bring about greater integration within the Indo-Pacific region by undertaking several infra-structure projects. India and Japan have already started collaborating on projects in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Kenya to this end.

Lastly, a significant development in Modi’s connectivity programme relates to the construction of India’s first high-speed Shinkansen rail system connecting Ahmedabad and Mumbai with the financial assistance of Japan.<9> The project aims to ensure smooth mobility, improve connectivity, and enhance regional economic development. The project is also intended to contribute to India’s ‘Make in India’ programme and generate employment in the region.

This article originally appeared in special report Looking Back looking Ahead.

End Notes

<1> “India-Japan Vision Statement,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 29 October 2018.

<2> Ibid., para 15.

<3> Ibid.

<4> “India-Japan Economic Relations,” Indian Embassy Tokyo, 2019.

<5> Ibid., para 4.

<6> “Launch of India-Japan Act East Forum,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 5 December 2017.

<7> Ibid., para 2.

<8> Vikas Dhoot, “An Abe-Modi Plan for Africa,” The Hindu, 24 May 2017.

<9> Neha Dasgupta, Rupam Jain and Yuka Obayashi, “Japan in Driver’s Seat for Indian Bullet Train Deals,” Reuters, 18 January 2018.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV